LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

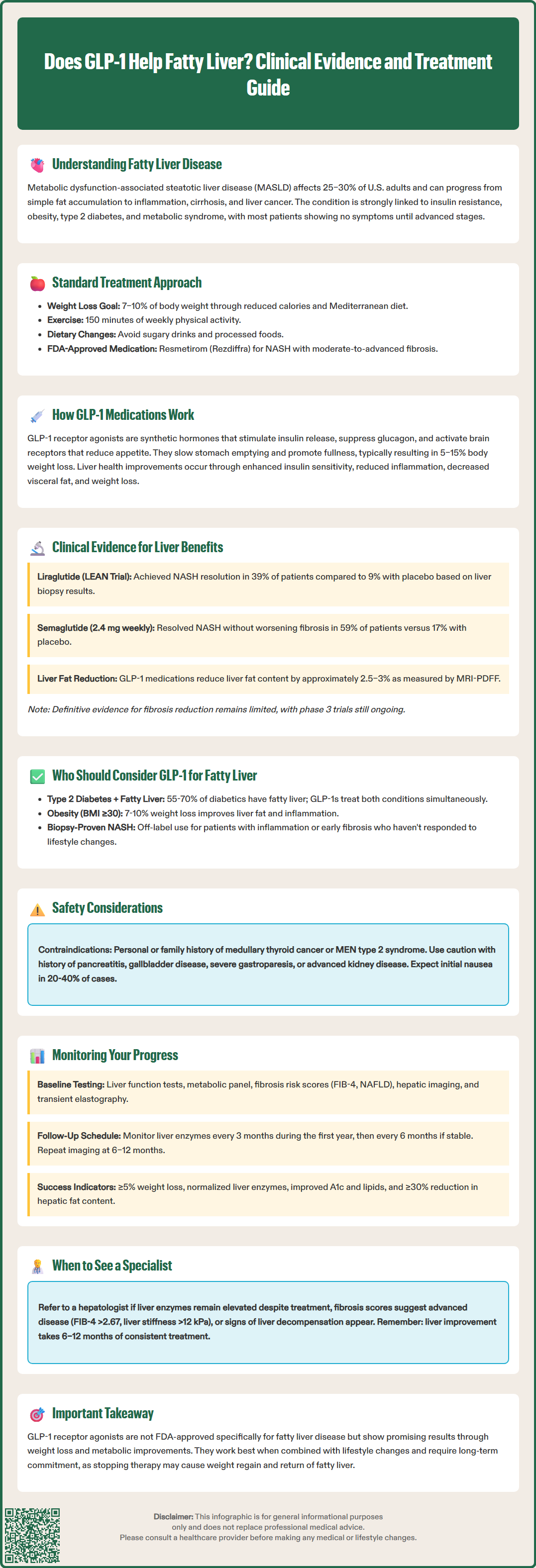

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists show promise for treating fatty liver disease, particularly in patients with type 2 diabetes or obesity. These medications, originally developed for diabetes management, improve multiple metabolic pathways implicated in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), formerly known as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Clinical trials demonstrate that GLP-1 drugs reduce liver fat content, improve liver enzymes, and in some cases achieve resolution of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). While no GLP-1 medication currently carries FDA approval specifically for fatty liver disease, accumulating evidence supports their therapeutic potential through weight loss, improved insulin sensitivity, and reduced systemic inflammation.

Quick Answer: GLP-1 receptor agonists improve fatty liver disease by reducing liver fat content, improving liver enzymes, and achieving NASH resolution in clinical trials, primarily through weight loss and enhanced insulin sensitivity.

We offer compounded medications and Zepbound®. Compounded medications are prepared by licensed pharmacies and are not FDA-approved. References to Wegovy®, Ozempic®, Rybelsus®, Mounjaro®, or Saxenda®, or other GLP-1 brands, are informational only. Compounded and FDA-approved medications are not interchangeable.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), now increasingly referred to as metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), affects approximately 25–30% of adults in the United States. This condition occurs when excess fat accumulates in the liver in individuals who consume little to no alcohol. The spectrum ranges from simple steatosis (fat accumulation without significant inflammation) to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which involves inflammation and hepatocyte injury that can progress to fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma.

The pathophysiology of MASLD is closely linked to insulin resistance, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. Risk factors include central adiposity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and sedentary lifestyle. Many patients remain asymptomatic until advanced disease develops, making incidental detection through elevated liver enzymes or imaging studies common.

Historically, treatment options have been limited to lifestyle modification—specifically weight loss of 7–10% of body weight, which can improve hepatic steatosis and inflammation. Dietary interventions emphasizing reduced caloric intake, Mediterranean diet patterns, and avoidance of fructose-sweetened beverages form the cornerstone of management. Regular physical activity, targeting at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise weekly, provides additional metabolic benefits.

In 2024, the FDA approved resmetirom (Rezdiffra) for adults with noncirrhotic NASH with F2–F3 fibrosis, marking the first approved pharmacotherapy specifically for this condition. Prior to this, vitamin E (800 IU daily) has shown histologic benefit in non-diabetic, biopsy-proven NASH patients in clinical trials, though long-term safety concerns exist including potential increased risks of hemorrhagic stroke and prostate cancer in men. Pioglitazone has demonstrated efficacy but carries risks of weight gain, fluid retention, heart failure, and bone fractures. The limited treatment landscape has created significant interest in repurposing existing drugs, particularly glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, which address multiple metabolic pathways implicated in fatty liver disease.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) is an incretin hormone secreted by intestinal L-cells in response to nutrient intake. GLP-1 receptor agonists are synthetic analogs or modified versions of this endogenous hormone, designed to resist degradation by the enzyme dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4), thereby extending their duration of action from minutes to hours or days.

The primary mechanism of GLP-1 receptor agonists involves binding to GLP-1 receptors on pancreatic beta cells, stimulating glucose-dependent insulin secretion. This glucose-dependent mechanism reduces hypoglycemia risk compared to insulin or sulfonylureas. Simultaneously, these medications suppress glucagon secretion from pancreatic alpha cells, reducing hepatic glucose production. GLP-1 receptors are also present in the central nervous system, particularly in appetite-regulating centers of the hypothalamus, where activation promotes satiety and reduces food intake.

Beyond glycemic control, GLP-1 receptor agonists slow gastric emptying, prolonging the sensation of fullness after meals. This multifaceted approach typically results in significant weight loss—often 5–15% of body weight depending on the specific agent and dose. Cardiovascular benefits have been demonstrated with several GLP-1 receptor agonists, including reduced risk of major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with established cardiovascular disease.

Regarding hepatic effects, GLP-1 receptors are expressed at low levels in hepatocytes, though their functional significance remains debated. The mechanisms by which these medications improve liver health appear to be primarily indirect. Benefits largely stem from improved insulin sensitivity, reduced systemic inflammation, decreased visceral adiposity, and weight loss—all factors that contribute to the pathogenesis of fatty liver disease. Any direct hepatic effects are less well-established. The combination of metabolic improvements positions GLP-1 receptor agonists as potentially valuable therapeutic agents for MASLD and NASH.

Important safety considerations include contraindications in patients with personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma or multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2, caution in those with a history of pancreatitis, increased risk of gallbladder disease, potential for acute kidney injury with dehydration, and possible worsening of diabetic retinopathy with rapid glycemic improvement.

Accumulating clinical evidence demonstrates that GLP-1 receptor agonists can improve markers of fatty liver disease, though the strength of evidence varies by outcome measure and specific medication. Multiple randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses have examined hepatic endpoints in patients with type 2 diabetes and NAFLD.

Imaging studies using magnetic resonance imaging-proton density fat fraction (MRI-PDFF), a validated non-invasive method for quantifying hepatic steatosis, have shown significant reductions in liver fat content with GLP-1 therapy. Liver biopsy remains the diagnostic gold standard for NASH, but MRI-PDFF provides a reliable measure for monitoring steatosis changes. Meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials have found that GLP-1 receptor agonists reduced liver fat content by approximately 2.5–3% absolute reduction in PDFF compared to placebo or active comparators. These improvements correlate with weight loss magnitude, though some studies suggest potential benefits beyond weight reduction alone.

Biochemical markers also improve with GLP-1 treatment. Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels, which reflect hepatocellular injury, typically decrease during GLP-1 therapy. Reductions in gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) and improvements in lipid profiles further support metabolic benefits. However, liver enzyme normalization does not necessarily indicate resolution of inflammation or fibrosis.

Histologic evidence from liver biopsies—the definitive method for diagnosing and staging NASH—has been more limited but encouraging. The LEAN trial demonstrated that liraglutide achieved NASH resolution in 39% of patients versus 9% with placebo. More recently, a phase 2 trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine showed that high-dose semaglutide (2.4 mg weekly) achieved NASH resolution without worsening of fibrosis in 59% of patients versus 17% with placebo. However, the trial did not demonstrate statistically significant improvement in fibrosis stage, which determines long-term prognosis. Phase 3 studies specifically targeting NASH as a primary indication are ongoing. These findings suggest that GLP-1 receptor agonists, particularly at higher doses, may offer disease-modifying benefits beyond symptomatic improvement.

Several GLP-1 receptor agonists are FDA-approved for type 2 diabetes management and, in some cases, chronic weight management. While none currently carry a specific FDA indication for fatty liver disease or NASH, their metabolic effects provide rationale for use in patients with concurrent hepatic steatosis. In contrast, resmetirom (Rezdiffra) received FDA approval in 2024 specifically for noncirrhotic NASH with F2–F3 fibrosis.

Currently available GLP-1 receptor agonists include:

Exenatide (Byetta, Bydureon BCise): Available as twice-daily or once-weekly formulations. Limited specific data exist regarding hepatic outcomes, though metabolic improvements suggest potential benefit.

Liraglutide (Victoza, Saxenda): Approved for type 2 diabetes (1.8 mg daily) and chronic weight management (3.0 mg daily). The LEAN trial specifically demonstrated histologic improvement in NASH patients, with resolution of NASH in 39% of liraglutide-treated patients. Liraglutide 3.0 mg is associated with approximately 5–8% weight loss.

Semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy, Rybelsus): Available as once-weekly injection (0.5–2.0 mg for diabetes; 2.4 mg for weight management) or daily oral tablet. Semaglutide produces greater weight loss (10–15%) than earlier GLP-1 agonists and has shown promising results in NASH trials. Phase 3 studies examining semaglutide specifically for NASH are ongoing.

Dulaglutide (Trulicity): Once-weekly injection approved for type 2 diabetes, with demonstrated cardiovascular benefits. Hepatic-specific data are more limited compared to liraglutide and semaglutide.

Tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Zepbound): A dual GLP-1/GIP receptor agonist approved for diabetes and weight management. While technically not a pure GLP-1 agonist, tirzepatide produces substantial weight loss (15–20%) and marked metabolic improvements, with emerging evidence of significant hepatic fat reduction.

All GLP-1 receptor agonists carry a boxed warning for risk of thyroid C-cell tumors, including medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC), and are contraindicated in patients with personal or family history of MTC or Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia syndrome type 2. Additional safety considerations include pancreatitis risk, gallbladder disease, potential for acute kidney injury with dehydration, and possible worsening of diabetic retinopathy with rapid glycemic improvement.

It is important to note that while these medications improve metabolic parameters associated with fatty liver disease, prescribing for NASH specifically represents off-label use until formal FDA approval for this indication is granted.

GLP-1 receptor agonists may be appropriate for select patients with fatty liver disease, particularly those with concurrent metabolic conditions. Clinical decision-making should be individualized, considering the patient's complete metabolic profile, disease severity, and treatment goals.

Ideal candidates typically include patients with:

Type 2 diabetes and NAFLD/MASLD: This represents the most straightforward indication, as GLP-1 agonists are FDA-approved for diabetes management. Given the high prevalence of fatty liver in diabetic patients (estimated at 55–70%), initiating or switching to a GLP-1 agonist addresses both conditions simultaneously. American Diabetes Association guidelines recognize GLP-1 receptor agonists as preferred agents for patients with diabetes and established cardiovascular disease or chronic kidney disease.

Obesity with hepatic steatosis: Patients with BMI ≥30 kg/m² (or ≥27 kg/m² with weight-related comorbidities) and documented fatty liver may benefit from GLP-1 agonists approved for chronic weight management. Weight loss of 7–10% significantly improves hepatic steatosis and inflammation, making these agents valuable tools.

Biopsy-proven NASH: Patients with histologically confirmed NASH, particularly those with significant inflammation or early fibrosis (F1-F2), may be considered for off-label GLP-1 therapy, especially if they have failed lifestyle modification or have contraindications to other therapies like vitamin E or pioglitazone. Patients with F2–F3 fibrosis may be candidates for FDA-approved resmetirom.

Metabolic syndrome with elevated liver enzymes: Patients presenting with multiple metabolic risk factors (central obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, impaired fasting glucose) and persistently elevated ALT/AST may benefit from the comprehensive metabolic improvements offered by GLP-1 therapy.

Contraindications and cautions include:

Personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma or multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2 (absolute contraindication)

History of pancreatitis (relative contraindication; risk-benefit assessment required)

Gallbladder disease (increased risk of gallstones with rapid weight loss)

Severe gastroparesis or gastrointestinal disorders

Advanced chronic kidney disease (avoid exenatide if eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m²; others generally do not require dose adjustment but monitor for dehydration)

Diabetic retinopathy (monitor closely, especially with rapid glycemic improvement)

Pregnancy or planned pregnancy

Patients should have realistic expectations regarding treatment duration, potential side effects (particularly nausea, which affects 20–40% initially), and the need for continued lifestyle modification. GLP-1 therapy is not a substitute for dietary changes and physical activity but rather an adjunct to comprehensive lifestyle intervention.

Appropriate monitoring ensures treatment efficacy and safety when using GLP-1 receptor agonists for patients with fatty liver disease. A structured approach to surveillance helps identify treatment responders and detect potential complications.

Baseline assessment should include:

Comprehensive metabolic panel with liver function tests (ALT, AST, alkaline phosphatase, total bilirubin, albumin)

Fasting lipid panel and hemoglobin A1c

Complete blood count and platelet count

Calculation of fibrosis risk using non-invasive scores (FIB-4, NAFLD Fibrosis Score)

Hepatic imaging (ultrasound or controlled attenuation parameter [CAP] via transient elastography) to assess steatosis

Exclusion of other liver diseases (viral hepatitis, alcohol use disorder, hemochromatosis, autoimmune hepatitis)

Assessment for advanced fibrosis using transient elastography (FibroScan) when available

Follow-up monitoring typically includes:

Liver enzymes every 3 months during the first year, then every 6 months if stable

Hemoglobin A1c every 3 months (for diabetic patients)

Weight and BMI at each visit

Assessment of gastrointestinal side effects and medication adherence

Repeat imaging at 6–12 months to assess treatment response (reduction in hepatic fat content)

Repeat fibrosis assessment at 12–24 months in patients with baseline advanced fibrosis

Treatment response indicators include:

Weight loss ≥5% of baseline body weight (associated with improved steatosis)

Reduction in ALT/AST levels toward normal range

Improvement in metabolic parameters (A1c, lipids, blood pressure)

Decreased hepatic fat content on imaging (≥30% relative reduction considered clinically meaningful)

Referral to hepatology is warranted for:

Persistently elevated liver enzymes despite treatment

Clinical or laboratory evidence of hepatic decompensation (ascites, encephalopathy, coagulopathy)

FIB-4 score >2.67 or NAFLD Fibrosis Score >0.676 (suggesting advanced fibrosis)

Liver stiffness measurement >12 kPa on transient elastography (suggesting advanced fibrosis; 8–12 kPa is indeterminate)

Consideration of liver biopsy for definitive staging

Evaluation for hepatocellular carcinoma screening in cirrhotic patients (ultrasound with or without AFP every 6 months)

Patients should be counseled that improvement in liver health is gradual, typically requiring 6–12 months of consistent treatment and lifestyle modification. Discontinuation of GLP-1 therapy may result in weight regain and recurrence of hepatic steatosis, emphasizing the need for long-term treatment strategies. Regular communication between primary care providers, endocrinologists, and hepatologists optimizes outcomes for patients with fatty liver disease receiving GLP-1 therapy.

No GLP-1 receptor agonist currently has FDA approval specifically for fatty liver disease or NASH. However, these medications are approved for type 2 diabetes and chronic weight management, and clinical trials demonstrate significant improvements in liver fat content and inflammation. Prescribing GLP-1 drugs specifically for NASH represents off-label use.

Improvement in liver health with GLP-1 therapy is gradual, typically requiring 6–12 months of consistent treatment combined with lifestyle modification. Repeat imaging at 6–12 months helps assess treatment response, with clinically meaningful improvement defined as at least a 30% relative reduction in hepatic fat content.

Semaglutide at higher doses (2.4 mg weekly) has shown the most robust evidence for NASH resolution in clinical trials, achieving resolution in 59% of patients. Liraglutide also demonstrated histologic improvement in the LEAN trial with 39% NASH resolution. The greater weight loss achieved with semaglutide may contribute to its enhanced hepatic benefits.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.