LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

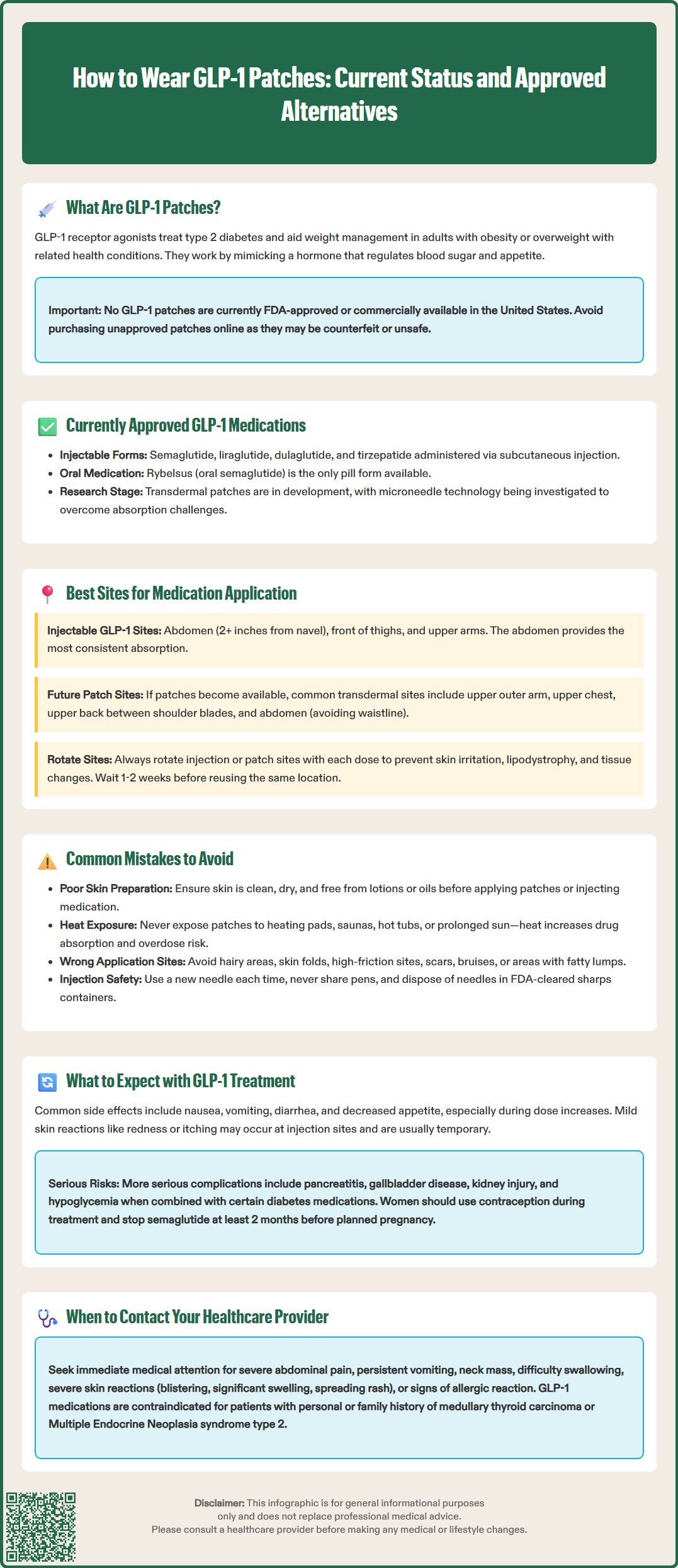

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists are FDA-approved medications for type 2 diabetes and weight management, but currently no GLP-1 patches are approved for use in the United States. While transdermal patch delivery systems are under investigation, all commercially available GLP-1 therapies require subcutaneous injection (semaglutide, liraglutide, dulaglutide, tirzepatide) or oral administration (Rybelsus). Patients should avoid purchasing unapproved GLP-1 patches marketed online, as these products may be counterfeit or unsafe. This article explains the current status of GLP-1 patch development, proper administration techniques for approved injectable formulations, and what patients should know about transdermal medication delivery principles if such products become available in the future.

Quick Answer: No GLP-1 patches are currently FDA-approved or commercially available in the United States for clinical use.

We offer compounded medications and Zepbound®. Compounded medications are prepared by licensed pharmacies and are not FDA-approved. References to Wegovy®, Ozempic®, Rybelsus®, Mounjaro®, or Saxenda®, or other GLP-1 brands, are informational only. Compounded and FDA-approved medications are not interchangeable.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists are medications primarily used for managing type 2 diabetes and, in some formulations, for weight management in adults with BMI ≥30 kg/m² or ≥27 kg/m² with weight-related comorbidities. While most GLP-1 medications are administered via subcutaneous injection (such as semaglutide, liraglutide, dulaglutide, or tirzepatide), with oral semaglutide (Rybelsus) as the only FDA-approved non-injectable option, transdermal patch delivery systems represent an emerging area of pharmaceutical development. It is important to note that as of current FDA approvals, there are no commercially available GLP-1 patches approved for clinical use in the United States. Patients should avoid purchasing or using any unapproved GLP-1 patches marketed online, as these may be counterfeit or unsafe.

The concept behind transdermal GLP-1 delivery involves using a patch applied to the skin that would theoretically release medication through the dermal layers into systemic circulation. This mechanism would bypass the gastrointestinal tract and provide steady-state drug levels over an extended period. GLP-1 receptor agonists work by mimicking the action of endogenous GLP-1, a hormone that stimulates insulin secretion in a glucose-dependent manner, suppresses glucagon release, slows gastric emptying, and promotes satiety through central nervous system pathways.

Research into transdermal delivery of peptide medications faces significant challenges due to the large molecular size of GLP-1 analogs and the skin's natural barrier function. While microneedle patches and other advanced delivery technologies are under investigation in preclinical and early clinical studies, patients should be aware that any information about "wearing" GLP-1 patches currently refers to investigational products not yet available for prescription use. Patients seeking GLP-1 therapy should consult their healthcare provider about FDA-approved injectable or oral formulations and proper administration techniques for those products.

All FDA-approved GLP-1 medications carry important safety information, including contraindications for patients with personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) or Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia syndrome type 2 (MEN2).

Because no GLP-1 patches are currently FDA-approved or commercially available, there is no established clinical protocol for their application. However, understanding general principles of transdermal medication delivery can provide context for how such products might theoretically be used if they become available in the future. For any approved transdermal medication, patients must always follow the specific instructions in the FDA-approved Medication Guide and prescribing information.

For any transdermal medication system, proper application typically involves several key steps. First, wash and dry your hands thoroughly before handling the patch. The application site should be clean, dry, and free from cuts, irritation, or excessive hair. The skin should be washed with mild soap and water, then thoroughly dried—avoiding lotions, oils, or powders that could interfere with adhesion. If necessary, hair may be clipped (not shaved) to improve adhesion. Second, the patch would be removed from its protective packaging immediately before application, taking care not to touch the adhesive or medication-containing surface. Third, the patch would be applied with firm pressure, typically for 10-30 seconds, ensuring complete contact with the skin and smooth adherence without wrinkles or air bubbles.

Importantly, patients using transdermal medications should avoid exposing the patch to external heat sources such as heating pads, electric blankets, hot tubs, saunas, or prolonged direct sunlight, as heat can increase drug absorption and potentially cause overdose. If a patch becomes partially detached, do not attempt to reattach it with tape or other adhesives unless specifically instructed by the product labeling. Instead, follow the manufacturer's instructions regarding replacement.

Patients currently using injectable GLP-1 medications should follow the specific administration instructions provided with their prescribed product. These typically involve subcutaneous injection into the abdomen, thigh, or upper arm using a prefilled pen device. Proper injection technique, including rotating injection sites, ensuring correct dosing, never sharing pens with others, using a new needle for each injection, and removing the needle after use, is essential for therapeutic efficacy and safety. Healthcare providers and diabetes educators can provide hands-on training for patients new to injectable GLP-1 therapy. Used needles should be disposed of in an FDA-cleared sharps container according to local regulations.

While there are no approved GLP-1 patches with established application sites, general principles of transdermal drug delivery provide insight into optimal placement considerations. For any future FDA-approved transdermal medication, patients must follow the specific sites and rotation schedule detailed in the product's prescribing information.

Common sites for transdermal medication delivery include the upper outer arm, upper chest, upper back between the shoulder blades, and the abdomen (avoiding the waistline). These areas generally provide adequate skin surface area, relatively consistent drug absorption, and can be easily accessed for application while remaining concealed under clothing. The selection of specific sites depends on factors including skin thickness, local blood flow, hair density, and the potential for the patch to be dislodged by clothing or physical activity. For self-application without assistance, the upper arm, chest, and abdomen are typically most accessible.

Site rotation is a fundamental principle in transdermal therapy to minimize local skin irritation and prevent the development of contact dermatitis. When using any transdermal medication, patients should avoid applying a new patch to the same exact location for at least one to two weeks, or as specified in the product labeling. This practice allows the skin to recover and reduces the cumulative irritant effect of the adhesive and medication.

For patients currently using injectable GLP-1 medications, recommended injection sites include the abdomen (at least 2 inches from the navel), the front of the thighs, and the upper arms. Rotating among these sites with each injection helps prevent lipodystrophy—changes in subcutaneous fat tissue that can affect medication absorption. Patients should never inject into areas with lipohypertrophy (fatty lumps), scars, bruises, or skin abnormalities. The abdomen typically provides the most consistent absorption for subcutaneous injections, though all approved sites are clinically effective when proper technique is used. Never share injection pens or devices with others, even if the needle has been changed, as this poses serious infection risks.

Although GLP-1 patches are not currently FDA-approved, understanding common errors associated with transdermal medication use provides valuable context. The most frequent mistake with any transdermal system is inadequate skin preparation, which can compromise drug absorption and patch adhesion. Applying patches to skin that is damp, oily, or covered with lotion creates a barrier that prevents proper contact and may lead to premature detachment or inconsistent medication delivery.

Another critical error is applying patches to inappropriate body sites—areas with excessive hair, skin folds, or locations subject to frequent movement or friction. These sites increase the likelihood of patch displacement and may result in subtherapeutic drug levels. Similarly, cutting or modifying patches to adjust dosing is dangerous and should never be attempted, as this can cause rapid, uncontrolled drug release and potential overdose.

Exposing transdermal patches to external heat sources (heating pads, saunas, hot tubs, prolonged sun exposure) can significantly increase drug absorption and potentially cause overdose. Patients should also avoid wearing multiple patches simultaneously unless specifically directed by their healthcare provider, as this can lead to accidental overdosing. Never cover patches with occlusive dressings or tape unless the product labeling specifically permits this practice.

Failure to rotate application sites adequately represents another common mistake. Repeatedly applying patches to the same location can cause contact dermatitis, skin sensitization, or localized tissue changes that impair drug absorption. Patients should maintain a rotation schedule and visually inspect previous application sites for persistent redness, itching, or skin changes that might indicate an adverse reaction.

For patients using currently available injectable GLP-1 medications, common errors include injecting into the same site repeatedly, failing to allow refrigerated medication to reach room temperature before injection, not rotating injection sites properly, and incorrect pen device technique. Injecting cold medication can increase injection site discomfort, while poor site rotation may lead to lipohypertrophy or lipoatrophy. Patients should never share pens, should use a new needle for each injection, and should not store pens with needles attached. Proper disposal of used needles in FDA-cleared sharps containers is essential for safety. The FDA provides guidance on safe sharps disposal at fda.gov/safesharpsdisposal.

For any transdermal medication system, the prescribed wear time is determined by the drug's pharmacokinetic profile and the patch's delivery technology. Transdermal patches typically remain in place for periods ranging from 24 hours to seven days, depending on the specific medication and formulation. Since no GLP-1 patches are currently FDA-approved, there is no established wear schedule for such products. If GLP-1 patches become available in the future, the manufacturer's prescribing information would specify the exact duration of wear, replacement schedule, and guidance for bathing, swimming, and other activities.

When changing any transdermal patch, patients should remove the old patch carefully, fold it in half with the adhesive sides together, and dispose of it safely according to the medication guide—typically in a sealed container out of reach of children and pets. The new patch should be applied to a different site following the rotation principles discussed earlier. Patients should note the date and time of application to maintain an accurate schedule.

During the initial period of using any new transdermal medication, patients may experience local skin reactions such as mild redness, itching, or irritation at the application site. These reactions are often transient and resolve within a few hours after patch removal. However, persistent or severe skin reactions, including blistering, significant swelling, or spreading rash, warrant immediate medical evaluation and may indicate contact dermatitis or allergic sensitization.

For injectable GLP-1 medications currently in use, patients should be aware of common side effects including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and decreased appetite, particularly during dose escalation. These gastrointestinal effects typically diminish over time as the body adjusts to the medication. More serious potential adverse effects include pancreatitis, gallbladder disease (cholelithiasis, cholecystitis), acute kidney injury (especially with dehydration), and increased risk of hypoglycemia when used with insulin or sulfonylureas. Semaglutide may worsen diabetic retinopathy complications in some patients. Injection site reactions—such as redness, swelling, or bruising—are generally mild and self-limited.

Patients should contact their healthcare provider if they experience severe abdominal pain, persistent vomiting, signs of pancreatitis, symptoms of gallbladder disease, or symptoms of thyroid tumors (neck mass, difficulty swallowing, persistent hoarseness). Women of childbearing potential should use effective contraception while taking GLP-1 medications, and semaglutide should be discontinued at least 2 months before a planned pregnancy. Serious adverse events should be reported to the FDA MedWatch program. Regular follow-up with healthcare providers ensures appropriate monitoring of glycemic control, weight changes, and potential adverse effects.

No, there are currently no FDA-approved GLP-1 patches available for clinical use in the United States. All approved GLP-1 medications require subcutaneous injection or oral administration (Rybelsus), and patients should avoid purchasing unapproved patches marketed online.

FDA-approved GLP-1 medications are administered via subcutaneous injection (semaglutide, liraglutide, dulaglutide, tirzepatide) into the abdomen, thigh, or upper arm, or taken orally as Rybelsus. Proper injection technique includes rotating sites and using a new needle for each injection.

Transdermal delivery of GLP-1 medications faces significant challenges due to the large molecular size of GLP-1 analogs and the skin's natural barrier function. While microneedle patches and advanced delivery technologies are under investigation in preclinical and early clinical studies, no products have completed the FDA approval process.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.