LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

Is berberine a GLP-1 agonist? This question has gained traction as social media influencers tout berberine as "nature's Ozempic," prompting patients and clinicians to examine whether this botanical supplement truly mimics prescription incretin therapies. Berberine, an alkaloid compound derived from plants like barberry and goldenseal, has demonstrated modest metabolic effects in research studies. However, its mechanism of action differs fundamentally from pharmaceutical GLP-1 receptor agonists like semaglutide and liraglutide. Understanding these distinctions is essential for patients with type 2 diabetes and healthcare providers navigating treatment decisions in an era of widespread supplement marketing and misinformation.

Quick Answer: Berberine is not a GLP-1 agonist and does not directly bind to or activate GLP-1 receptors like pharmaceutical medications such as semaglutide or liraglutide.

We offer compounded medications and Zepbound®. Compounded medications are prepared by licensed pharmacies and are not FDA-approved. References to Wegovy®, Ozempic®, Rybelsus®, Mounjaro®, or Saxenda®, or other GLP-1 brands, are informational only. Compounded and FDA-approved medications are not interchangeable.

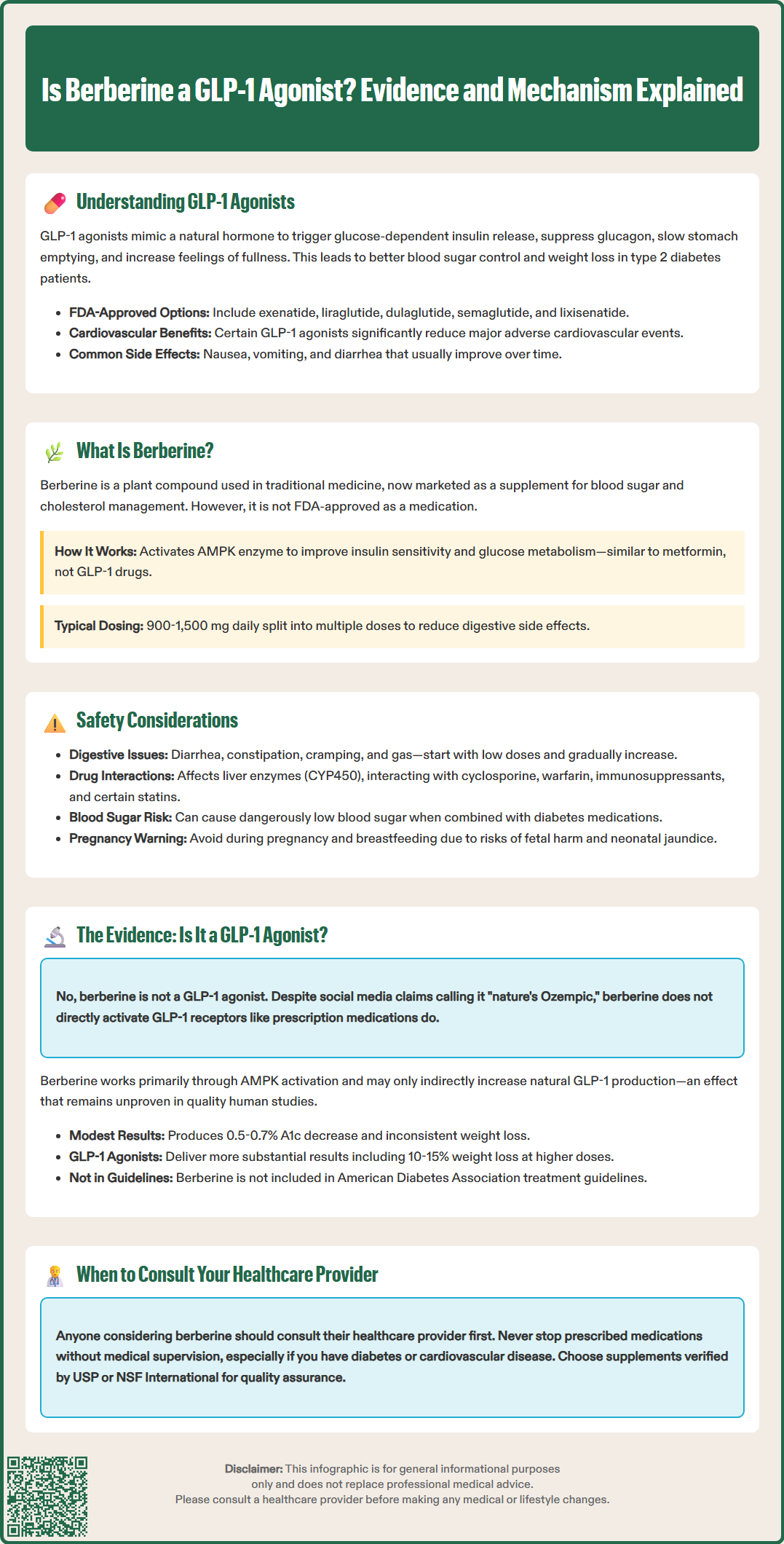

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists represent a class of medications that mimic the action of the naturally occurring incretin hormone GLP-1. These agents bind directly to GLP-1 receptors on pancreatic beta cells, triggering a cascade of physiological responses that improve glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. The mechanism involves glucose-dependent insulin secretion, meaning insulin release occurs primarily when blood glucose levels are elevated, thereby reducing the risk of hypoglycemia when used as monotherapy.

Beyond their effects on insulin secretion, GLP-1 agonists suppress glucagon release from pancreatic alpha cells, slow gastric emptying, and promote satiety through central nervous system pathways. These multifaceted actions contribute to both improved glycemic control and weight reduction, which has made this drug class particularly valuable for patients with type 2 diabetes who are overweight or obese. FDA-approved GLP-1 receptor agonists include exenatide, liraglutide, dulaglutide, semaglutide, and lixisenatide. Tirzepatide is a dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist that acts on both incretin pathways.

The pharmacological profile of GLP-1 agonists extends beyond diabetes management. Cardiovascular outcome trials have demonstrated significant reductions in major adverse cardiovascular events with certain agents in this class (liraglutide, injectable semaglutide, and dulaglutide), leading to expanded indications for cardiovascular risk reduction. Common adverse effects include gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, which typically diminish with continued use. More serious safety concerns include pancreatitis, gallbladder disease, and a potential risk of diabetic retinopathy complications with semaglutide. These medications carry an FDA boxed warning for medullary thyroid carcinoma and are contraindicated in patients with a personal or family history of MTC or Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia syndrome type 2. When combined with insulin or sulfonylureas, GLP-1 agonists may increase the risk of hypoglycemia, requiring dose adjustments of these medications.

Understanding the precise mechanism by which GLP-1 agonists work is essential when evaluating whether other compounds, such as berberine, share similar pharmacological properties.

Berberine is an isoquinoline alkaloid extracted from various plants including Berberis species (barberry), Coptis chinensis (goldthread), and Hydrastis canadensis (goldenseal). This naturally occurring compound has been used in traditional Chinese and Ayurvedic medicine for centuries, primarily for gastrointestinal complaints and infections. In recent decades, berberine has gained attention in Western countries as a dietary supplement marketed for metabolic health, particularly for blood glucose management and lipid control.

The mechanism of action of berberine differs fundamentally from that of GLP-1 agonists. Based on preclinical and limited clinical studies, berberine's primary metabolic effects appear to occur through activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), an enzyme that serves as a cellular energy sensor. When activated, AMPK may enhance insulin sensitivity, increase glucose uptake in skeletal muscle, suppress hepatic gluconeogenesis, and improve lipid metabolism. This putative mechanism shares similarities with metformin, the first-line medication for type 2 diabetes, rather than with incretin-based therapies.

Additional mechanisms attributed to berberine in laboratory and animal studies include modulation of gut microbiota composition, inhibition of mitochondrial complex I, and effects on various signaling pathways including those involving insulin receptor substrate proteins. Some preliminary research suggests berberine may influence incretin secretion indirectly, but this does not make it a GLP-1 agonist in the pharmacological sense. The compound also demonstrates antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties through mechanisms independent of glucose metabolism.

Berberine is available in the United States as a dietary supplement, not as an FDA-approved medication. This regulatory distinction is important because supplements are not subject to the same rigorous testing, quality control, and safety monitoring as prescription pharmaceuticals. The FDA does not evaluate supplements for safety or efficacy before they reach the market. Consumers seeking berberine supplements may benefit from choosing products verified by independent organizations like USP or NSF International. Studied doses typically range from 900 to 1,500 mg daily, divided into two or three doses to minimize gastrointestinal side effects, though it's important to note that berberine has poor and variable oral bioavailability.

While berberine is generally well-tolerated at recommended doses, several safety considerations warrant attention. The most common adverse effects are gastrointestinal in nature, including diarrhea, constipation, abdominal cramping, and flatulence. These symptoms often occur at treatment initiation and may be mitigated by starting with lower doses and gradually increasing to the target dose. Unlike GLP-1 agonists, berberine does not typically cause nausea through delayed gastric emptying, though gastrointestinal discomfort remains the primary tolerability concern.

Berberine has potential for drug interactions based primarily on in vitro studies showing effects on cytochrome P450 enzymes, particularly CYP3A4, CYP2D6, and CYP2C9. The compound appears to act as both a substrate and inhibitor of these enzymes, which metabolize numerous medications. The most clinically documented interaction is with cyclosporine, where berberine can significantly increase blood levels, potentially requiring dose adjustments and therapeutic drug monitoring. Theoretical interactions may occur with anticoagulants (warfarin), antiplatelet agents, immunosuppressants (tacrolimus), and certain statins. Patients taking warfarin should have INR monitored if using berberine. Those taking multiple medications should consult their healthcare provider before initiating berberine supplementation.

Of particular concern for patients with diabetes, berberine may potentiate the glucose-lowering effects of antidiabetic medications, including insulin, sulfonylureas, and meglitinides, potentially increasing hypoglycemia risk. While this additive effect might seem beneficial, unmonitored combination therapy can lead to dangerously low blood glucose levels. Patients using berberine alongside prescription diabetes medications should implement more frequent blood glucose monitoring and work closely with their healthcare team to adjust medication doses as needed.

Berberine is not recommended during pregnancy due to potential risks to the fetus and concerns about neonatal jaundice from displacement of bilirubin, which could lead to kernicterus. Breastfeeding women should also avoid berberine as it may be excreted in breast milk and could harm the infant. Berberine should not be given to newborns or infants due to the risk of kernicterus. Individuals with liver disease should exercise caution, as rare cases of liver injury have been reported, and berberine undergoes hepatic metabolism. Those with severe kidney disease should also use berberine cautiously and under medical supervision, as specific guidance is limited given berberine's status as a supplement rather than a regulated pharmaceutical.

Berberine is not a GLP-1 agonist. Despite marketing claims and social media comparisons labeling berberine as "nature's Ozempic," there is no credible scientific evidence that berberine directly binds to or activates GLP-1 receptors. The fundamental distinction lies in the mechanism of action: GLP-1 agonists are receptor-specific molecules that directly stimulate GLP-1 receptors, while berberine exerts its metabolic effects primarily through AMPK activation and other pathways that do not involve direct GLP-1 receptor engagement.

Some research has explored whether berberine might indirectly influence the incretin system. A limited number of preclinical studies suggest that berberine may modestly increase endogenous GLP-1 secretion from intestinal L-cells, potentially through effects on gut microbiota or direct stimulation of enteroendocrine cells. However, these findings remain preliminary, inconsistent across studies, and have not been robustly demonstrated in well-designed human clinical trials. Even if berberine does increase endogenous GLP-1 levels to some degree, this indirect effect is mechanistically and clinically distinct from the direct receptor agonism provided by pharmaceutical GLP-1 agonists.

The clinical effects of berberine and GLP-1 agonists also differ substantially. Meta-analyses of berberine trials show modest reductions in hemoglobin A1c (approximately 0.5-0.7%) and fasting glucose, with variable effects on body weight, though many studies have methodological limitations and high heterogeneity. In contrast, GLP-1 agonists typically produce more substantial glycemic improvements and consistent, clinically significant weight loss. The higher-dose semaglutide formulation for obesity (Wegovy, 2.4 mg weekly) can produce 10-15% weight loss, while diabetes doses typically yield more modest reductions. The weight loss mechanism differs as well: GLP-1 agonists work through delayed gastric emptying and central appetite suppression, while berberine's weight effects, when present, likely relate to improved insulin sensitivity and metabolic efficiency.

Patients considering berberine as an alternative to prescription GLP-1 agonists should understand these are not interchangeable therapies. While berberine may offer modest metabolic benefits as an adjunct to lifestyle modifications, it cannot replace FDA-approved medications for patients who require them. The American Diabetes Association Standards of Care do not include berberine in evidence-based treatment algorithms, and patients with type 2 diabetes should not discontinue prescribed medications in favor of supplements without medical supervision. Those interested in berberine should discuss its use with their healthcare provider, particularly if they have diabetes, take other medications, or have cardiovascular disease, as professional guidance can help integrate supplements safely within an overall treatment plan while maintaining appropriate monitoring and medication management.

No, berberine cannot replace FDA-approved GLP-1 agonists for diabetes management. While berberine may offer modest metabolic benefits, it works through different mechanisms and produces smaller glycemic improvements than prescription GLP-1 medications, which remain the evidence-based standard of care.

GLP-1 agonists directly bind to and activate GLP-1 receptors on pancreatic cells, while berberine works primarily through AMPK activation and does not directly interact with GLP-1 receptors. This fundamental mechanistic difference means they are not pharmacologically equivalent therapies.

Berberine may potentiate glucose-lowering effects of diabetes medications, increasing hypoglycemia risk when combined with insulin, sulfonylureas, or meglitinides. Patients should consult their healthcare provider before adding berberine to their regimen and implement more frequent blood glucose monitoring if using both therapies.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.