LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

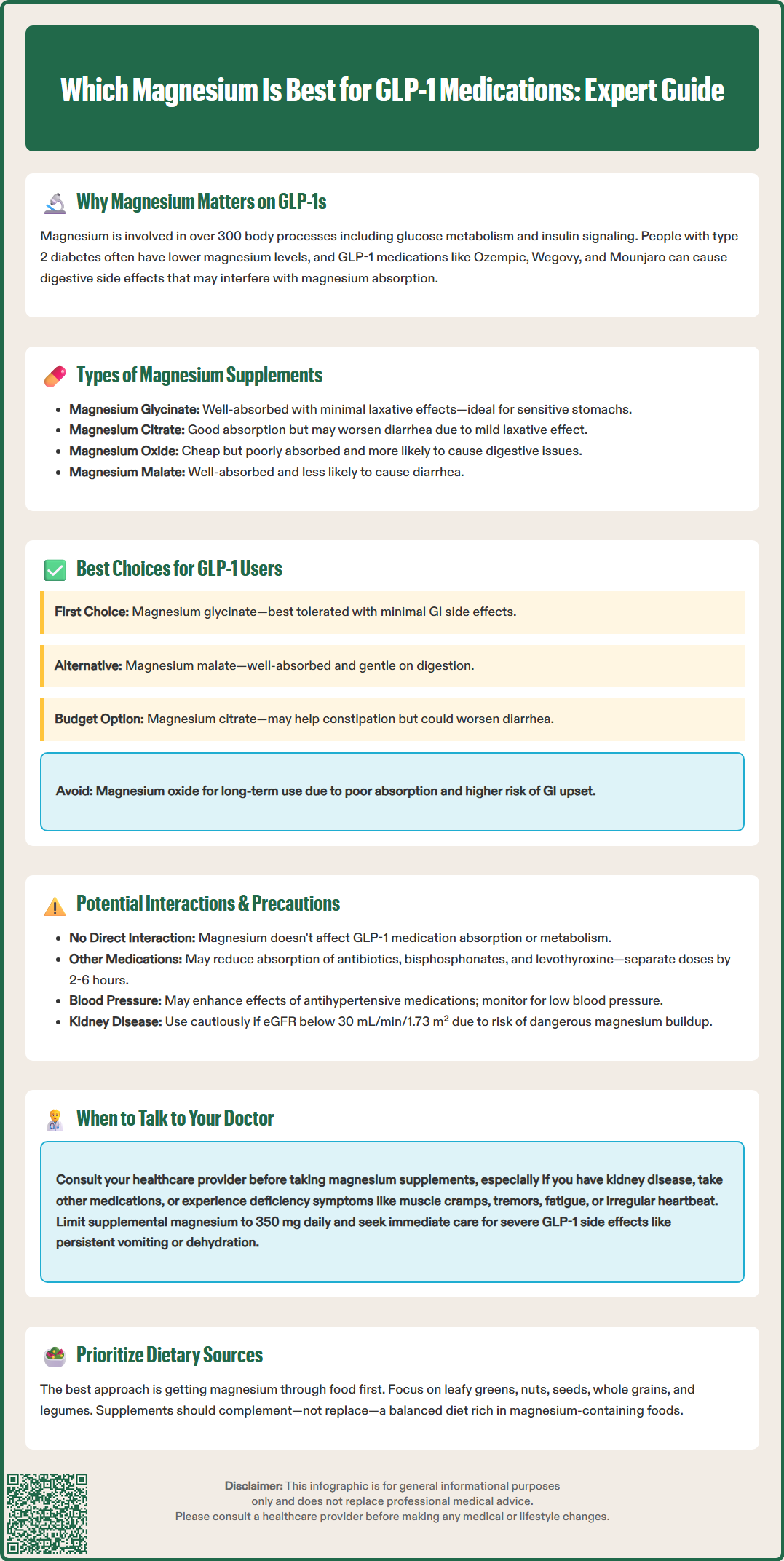

Magnesium glycinate is often considered the best magnesium supplement for individuals taking GLP-1 medications like semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy) or tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Zepbound) due to its good absorption and minimal gastrointestinal side effects. Since GLP-1 receptor agonists commonly cause nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation—particularly during dose titration—choosing a magnesium formulation that doesn't worsen these symptoms is clinically important. Magnesium plays a vital role in glucose metabolism, insulin signaling, and over 300 enzymatic reactions, making adequate intake essential for patients managing type 2 diabetes and obesity. This guide examines which magnesium forms are most suitable for GLP-1 users, considering absorption, tolerability, and individual patient factors.

Quick Answer: Magnesium glycinate is often the best choice for GLP-1 users due to its good absorption and minimal gastrointestinal side effects.

We offer compounded medications and Zepbound®. Compounded medications are prepared by licensed pharmacies and are not FDA-approved. References to Wegovy®, Ozempic®, Rybelsus®, Mounjaro®, or Saxenda®, or other GLP-1 brands, are informational only. Compounded and FDA-approved medications are not interchangeable.

Magnesium is an essential mineral involved in over 300 enzymatic reactions in the body, including glucose metabolism, insulin signaling, and gastrointestinal function. For individuals taking glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists such as semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy) and dulaglutide (Trulicity), or the dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Zepbound), maintaining adequate magnesium status may be particularly important.

These medications work by enhancing insulin secretion, suppressing glucagon release, slowing gastric emptying, and reducing appetite. These mechanisms contribute to improved glycemic control and weight loss in patients with type 2 diabetes and obesity. However, the gastrointestinal effects of these drugs—including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation—can potentially affect nutrient absorption and electrolyte balance. While there is no official link established between GLP-1 therapy and magnesium deficiency, the gastrointestinal side effects may theoretically increase the risk of suboptimal magnesium intake or absorption.

Magnesium deficiency (hypomagnesemia) has been associated with insulin resistance, impaired glucose tolerance, and increased cardiovascular risk. Studies suggest that individuals with type 2 diabetes often have lower magnesium levels compared to those without diabetes. Ensuring adequate magnesium intake through diet or supplementation may support metabolic health, though more research is needed to determine if this specifically complements the therapeutic effects of GLP-1 medications. Additionally, magnesium plays a role in muscle function, bone health, and neurological processes, making it a nutrient of broad clinical significance for patients managing chronic metabolic conditions.

Magnesium supplements are available in multiple formulations, each with distinct absorption characteristics and tolerability profiles. Understanding these differences is essential for selecting an appropriate supplement, particularly for patients experiencing gastrointestinal symptoms from GLP-1 therapy.

Magnesium citrate is one of the most commonly used forms, offering good bioavailability and relatively high absorption rates. It is often well-tolerated in moderate doses but may have a mild laxative effect, which could be problematic for GLP-1 users already experiencing diarrhea or gastrointestinal upset.

Magnesium glycinate (magnesium bound to the amino acid glycine) may be well-absorbed and generally well-tolerated with minimal laxative effects. This form is often recommended for individuals with sensitive gastrointestinal systems and may be suitable for those on GLP-1 medications.

Magnesium oxide is widely available and inexpensive but has lower bioavailability compared to other forms. It is more likely to cause gastrointestinal side effects, including diarrhea, and may be less efficient at raising serum magnesium levels.

Magnesium malate combines magnesium with malic acid and is generally well-absorbed. It may be gentler on the digestive system than magnesium oxide.

Magnesium threonate is a newer form that has been studied for potential neurological benefits, though evidence for its superiority in general magnesium repletion is limited. It is typically more expensive than other formulations.

Magnesium chloride and magnesium lactate are also available and offer moderate bioavailability. According to the NIH Office of Dietary Supplements, forms that dissolve well in liquid (such as citrate, chloride, and lactate) tend to be better absorbed than less soluble forms like oxide. The choice of formulation should balance absorption efficiency, gastrointestinal tolerability, cost, and individual patient factors.

For individuals taking GLP-1 receptor agonists or tirzepatide, several magnesium formulations may be appropriate based on individual tolerance and symptoms. No single form has been proven superior specifically for patients on these medications.

Magnesium glycinate is often considered a well-tolerated option due to its generally good absorption and minimal gastrointestinal side effects. Given that nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation are common adverse effects of GLP-1 medications—particularly during dose titration—selecting a magnesium supplement that does not exacerbate these symptoms is clinically prudent.

Magnesium glycinate is chelated to glycine, an amino acid that may enhance absorption and potentially reduce gastrointestinal distress. This makes it suitable for some patients who may already be experiencing gastrointestinal symptoms. Individual responses vary, however.

Magnesium malate is another option that some patients find well-tolerated. It is generally well-absorbed and may be less likely to cause diarrhea compared to magnesium citrate or oxide.

For patients without significant gastrointestinal sensitivity, magnesium citrate may be acceptable and is often more affordable. Its mild laxative properties should be considered in the context of GLP-1-related side effects—this could be problematic for those with diarrhea but potentially beneficial for those experiencing constipation.

Magnesium oxide is generally not recommended for GLP-1 users due to its relatively poor absorption and higher likelihood of causing gastrointestinal upset. While it may be useful as a short-term laxative, it is not ideal for long-term magnesium repletion.

The Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for magnesium is 400-420 mg daily for adult men and 310-320 mg for adult women. When supplementing, it's important to note that the Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) from supplements is 350 mg per day for adults. This UL does not apply to dietary magnesium from food sources. The amount of elemental magnesium differs by formulation; for example, magnesium glycinate products typically contain approximately 14% elemental magnesium by weight, though this can vary by manufacturer. Starting with a lower dose and gradually increasing based on tolerance is often advisable.

There is no established pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic interaction between magnesium supplements and GLP-1 receptor agonists or tirzepatide. These medications are peptide-based drugs administered subcutaneously, and their absorption, distribution, and metabolism are not significantly affected by oral magnesium supplementation. However, several indirect considerations are relevant.

First, magnesium can interact with other medications commonly prescribed to patients with type 2 diabetes or obesity. Magnesium may reduce the absorption of certain antibiotics (tetracyclines should be taken 2 hours before or 4-6 hours after magnesium; fluoroquinolones generally 2 hours before or 6 hours after) and bisphosphonates (separate by at least 2 hours and follow specific product labeling). Levothyroxine absorption may also be reduced by magnesium supplements, requiring separation by at least 4 hours.

Second, magnesium has a modest effect on blood pressure and may potentiate the effects of antihypertensive medications. While this is generally not clinically significant, patients on multiple blood pressure medications should be monitored for hypotension, particularly if initiating magnesium supplementation alongside GLP-1 therapy, which may also contribute to modest blood pressure reductions through weight loss.

Third, in patients with renal impairment, magnesium supplementation carries a risk of hypermagnesemia, as the kidneys are the primary route of magnesium excretion. GLP-1 medications are often used in patients with chronic kidney disease, and caution is warranted. Serum magnesium levels should be monitored in patients with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) below 30 mL/min/1.73 m².

Finally, while magnesium may theoretically improve insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism, there is insufficient evidence to suggest that supplementation significantly alters the glycemic efficacy of GLP-1 drugs. Patients should not rely on magnesium supplementation as a substitute for evidence-based diabetes management.

Patients taking GLP-1 medications should consult their healthcare provider before initiating magnesium supplementation, particularly if they have underlying medical conditions or are taking other medications. Several clinical scenarios warrant professional evaluation.

Symptoms of magnesium deficiency include muscle cramps, tremors, fatigue, weakness, irregular heartbeat, and numbness or tingling. While these symptoms are nonspecific, they may indicate hypomagnesemia, especially in patients with chronic diarrhea, malabsorption, or poorly controlled diabetes. Laboratory testing—typically a serum magnesium level—can confirm deficiency, though serum levels may not fully reflect total body magnesium stores.

Patients with chronic kidney disease should not initiate magnesium supplementation without medical supervision, as impaired renal excretion increases the risk of hypermagnesemia. Symptoms of magnesium toxicity include nausea, hypotension, bradycardia, respiratory depression, and in severe cases, cardiac arrest. Routine monitoring of renal function and electrolytes is essential in this population.

Individuals taking multiple medications—including antibiotics, diuretics, proton pump inhibitors, levothyroxine, or bisphosphonates—should discuss potential interactions with their healthcare provider. Adjustments in timing or dosing may be necessary to optimize therapeutic outcomes.

Persistent or severe gastrointestinal symptoms while on GLP-1 therapy, such as severe nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or severe abdominal pain, should prompt immediate medical evaluation. These symptoms may affect nutrient absorption and electrolyte balance, and could also indicate serious complications such as pancreatitis or gallbladder disease. Signs of dehydration, including excessive thirst, dry mouth, dizziness, or decreased urination, also require prompt medical attention.

Finally, patients should inform their provider if they are considering magnesium supplementation exceeding 350 mg daily (the Tolerable Upper Intake Level for supplemental magnesium), as excessive intake can cause diarrhea and other adverse effects. A balanced approach, incorporating dietary sources of magnesium—such as leafy greens, nuts, seeds, whole grains, and legumes—alongside appropriate supplementation, is generally recommended.

Yes, magnesium supplements are generally safe with GLP-1 medications, as there is no established pharmacokinetic interaction between them. However, consult your healthcare provider before starting supplementation, especially if you have kidney disease or take other medications.

Magnesium glycinate offers better absorption and causes fewer gastrointestinal side effects compared to magnesium oxide. Since GLP-1 medications commonly cause nausea and diarrhea, glycinate is less likely to worsen these symptoms.

The Recommended Dietary Allowance is 400-420 mg daily for adult men and 310-320 mg for adult women from all sources. The Tolerable Upper Intake Level from supplements alone is 350 mg daily; start with a lower dose and increase gradually based on tolerance.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.