LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

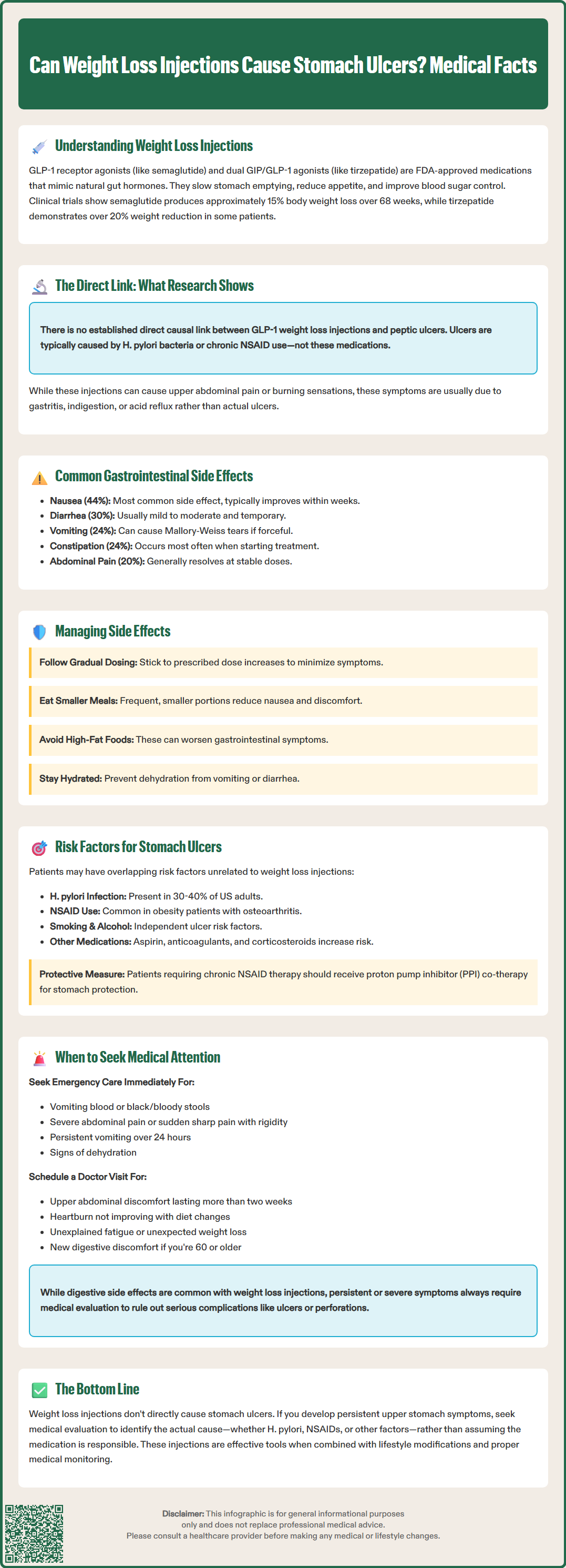

Weight loss injections, particularly GLP-1 receptor agonists like semaglutide (Wegovy, Ozempic) and dual GIP/GLP-1 agonists like tirzepatide (Zepbound, Mounjaro), have become widely prescribed for obesity management in the United States. While these FDA-approved medications are highly effective for weight reduction, patients and clinicians often have questions about their gastrointestinal safety profile. One common concern is whether these injections can cause stomach ulcers. Understanding the relationship between weight loss medications and peptic ulcer disease is essential for informed treatment decisions and appropriate symptom management during obesity therapy.

Quick Answer: There is currently no established direct causal link between GLP-1 receptor agonist weight loss injections and the development of stomach ulcers.

We offer compounded medications and Zepbound®. Compounded medications are prepared by licensed pharmacies and are not FDA-approved. References to Wegovy®, Ozempic®, Rybelsus®, Mounjaro®, or Saxenda®, or other GLP-1 brands, are informational only. Compounded and FDA-approved medications are not interchangeable.

Weight loss injections have emerged as a significant therapeutic option for obesity management in the United States. The most commonly prescribed medications in this category are glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists such as semaglutide (Wegovy, Ozempic), while tirzepatide (Zepbound, Mounjaro) represents a newer class that acts as a dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and GLP-1 receptor agonist. These medications were initially developed for type 2 diabetes management but have gained FDA approval for chronic weight management due to their substantial efficacy in promoting weight loss.

These medications work through multiple complementary mechanisms. They mimic the action of naturally occurring incretin hormones released by the intestine in response to food intake. They slow gastric emptying, which contributes to the sensation of fullness after meals and reduces appetite. They also act on appetite centers in the hypothalamus to decrease hunger signals and food cravings. Additionally, they enhance glucose-dependent insulin secretion and suppress inappropriate glucagon release, contributing to improved glycemic control in patients with diabetes.

The delayed gastric emptying is particularly relevant when considering gastrointestinal effects. By slowing the movement of food through the stomach, these medications help create a sense of satiety that supports reduced caloric intake. Clinical trials have demonstrated that patients using semaglutide 2.4 mg weekly can achieve average weight loss of approximately 15% of body weight over 68 weeks when combined with lifestyle modifications. Tirzepatide has shown even greater efficacy in clinical trials, with mean weight reductions exceeding 20% in certain patient populations.

It's important to note that these medications are not recommended for patients with severe gastrointestinal disease, including severe gastroparesis, according to their FDA prescribing information.

Currently, there is no established direct causal link between GLP-1 receptor agonist weight loss injections and the development of peptic ulcers (stomach or duodenal ulcers). Stomach ulcers, medically termed gastric ulcers, are breaks in the protective mucosal lining of the stomach, typically caused by infection with Helicobacter pylori bacteria or chronic use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). The FDA-approved prescribing information for semaglutide and tirzepatide does not list peptic ulcer disease as a known adverse effect or contraindication.

However, the gastrointestinal effects of these medications warrant careful consideration. The mechanism of delayed gastric emptying theoretically could affect the gastric environment, but this has not translated into increased ulcer formation in clinical trials. Some patients may experience symptoms that mimic ulcer-related discomfort, such as upper abdominal pain or burning sensations, but these are more commonly attributable to other gastrointestinal side effects like gastritis, dyspepsia, or gastroesophageal reflux.

It is important to distinguish between correlation and causation. Patients seeking weight loss treatment may have pre-existing risk factors for peptic ulcer disease, including NSAID use for obesity-related joint pain, H. pylori infection (present in approximately 30-40% of the US population, varying by age and ethnicity), or lifestyle factors such as smoking. If ulcer symptoms develop during treatment with weight loss injections, a thorough evaluation is necessary to identify the underlying cause rather than automatically attributing symptoms to the medication.

Other conditions that may present with similar symptoms include Mallory-Weiss tears (mucosal lacerations at the gastroesophageal junction), which can occur with forceful vomiting—a known side effect of these medications. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for alternative diagnoses and investigate appropriately when patients report persistent or severe upper gastrointestinal symptoms.

Gastrointestinal adverse effects are the most commonly reported side effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists and dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonists used for weight loss. Understanding these effects helps differentiate expected medication responses from potentially serious complications like peptic ulcers.

According to FDA prescribing information, the most frequent gastrointestinal side effects for semaglutide 2.4 mg (Wegovy) include:

Nausea (44% of patients)

Diarrhea (30% of patients)

Vomiting (24% of patients)

Constipation (24% of patients)

Abdominal pain (20% of patients)

Dyspepsia or indigestion (9% of patients)

For tirzepatide (Zepbound), similar gastrointestinal effects occur, with rates varying by dose.

These effects are generally dose-dependent and most pronounced during treatment initiation and dose escalation. The majority of gastrointestinal symptoms are mild to moderate in severity and tend to diminish over time as patients develop tolerance to the medication. Many patients report improvement in symptoms within several weeks of maintaining a stable dose, though individual experiences vary.

While delayed gastric emptying is an intended mechanism of these medications, in some cases it may be associated with more significant symptoms. Postmarketing reports have included cases of severe gastrointestinal adverse reactions, including reports of intestinal obstruction and ileus. Acute pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas) is a labeled warning for these medications, and acute gallbladder disease including cholecystitis is also noted in the prescribing information. Additionally, these medications carry a risk of acute kidney injury, particularly in the setting of severe gastrointestinal adverse reactions and dehydration.

Management strategies for common gastrointestinal side effects include gradual dose titration following FDA-approved schedules, eating smaller and more frequent meals, avoiding high-fat foods, staying well-hydrated, and temporarily reducing the dose if symptoms become intolerable. Antiemetic medications may be prescribed for persistent nausea, though they should be used judiciously and not as a substitute for appropriate dose adjustment.

While weight loss injections themselves are not directly linked to ulcer formation, patients undergoing obesity treatment may have multiple concurrent risk factors for developing peptic ulcer disease that require clinical attention and management.

Primary risk factors for peptic ulcers include:

Helicobacter pylori infection – the leading cause of peptic ulcers worldwide, present in approximately 30-40% of US adults

NSAID use – including ibuprofen, naproxen, and aspirin, which disrupt the protective gastric mucosa

Smoking – increases the risk of ulcer development and impairs healing

Excessive alcohol consumption – can damage the gastric lining and increase acid production

Physiological stress – severe illness, major surgery, or critical care situations

Previous ulcer history – significantly increases recurrence risk

Medication combinations – concurrent use of NSAIDs with anticoagulants, antiplatelets, or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) increases bleeding risk

Patients with obesity often have overlapping risk factors that may coincide with weight loss treatment. Many use NSAIDs regularly for obesity-related osteoarthritis or chronic pain conditions. Smoking rates may be elevated in certain patient populations seeking weight loss interventions.

Clinicians should conduct a thorough medication reconciliation before initiating weight loss injections, specifically inquiring about NSAID use, aspirin therapy, anticoagulants, and corticosteroids. For patients requiring chronic NSAID therapy, proton pump inhibitor (PPI) co-therapy should be considered for gastroprotection, particularly in those with additional risk factors. According to American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guidelines, testing for H. pylori is recommended for all patients with active or previous peptic ulcer disease. The ACG recommends a test-and-treat strategy for H. pylori using either urea breath testing or stool antigen testing, with appropriate pre-test medication holds (PPIs, antibiotics, and bismuth compounds).

Patient education should emphasize the importance of reporting new or worsening abdominal symptoms and avoiding self-medication with over-the-counter NSAIDs without medical guidance during weight loss treatment.

Patients using weight loss injections should be educated about distinguishing between expected gastrointestinal side effects and symptoms requiring urgent medical evaluation. While mild nausea and digestive discomfort are common and generally self-limiting, certain symptoms may indicate serious complications including peptic ulcer disease, perforation, or other acute abdominal pathology.

Seek immediate medical attention for:

Severe, persistent abdominal pain that does not resolve or worsens over hours

Vomiting blood (hematemesis) or material that looks like coffee grounds

Black, tarry stools (melena) or visible blood in stools, suggesting gastrointestinal bleeding

Severe nausea and vomiting preventing adequate fluid intake or lasting more than 24 hours

Signs of dehydration including decreased urination, dizziness, or confusion

Sudden, sharp abdominal pain with rigidity, potentially indicating perforation

Progressive dysphagia (difficulty swallowing)

Persistent vomiting despite medication adjustments

Schedule a non-urgent appointment for:

Persistent upper abdominal discomfort or burning sensation lasting more than two weeks

Recurrent dyspepsia not responding to dietary modifications

New or worsening heartburn or acid reflux symptoms

Unexplained fatigue potentially indicating anemia from chronic blood loss

Unintended, disproportionate, or symptomatic weight loss distinct from expected medication effects

According to American College of Gastroenterology guidelines, patients aged 60 or older with new-onset dyspepsia should undergo prompt endoscopic evaluation, as should patients of any age with alarm features.

When evaluating patients with concerning symptoms, clinicians should perform a comprehensive assessment including detailed history, physical examination, and appropriate investigations. Initial workup may include complete blood count to assess for anemia, comprehensive metabolic panel, lipase for suspected pancreatitis, and H. pylori testing (preferably stool antigen or urea breath test). Pregnancy testing should be considered where appropriate, and fecal occult blood testing may be indicated if GI bleeding is suspected. Upper endoscopy (esophagogastroduodenoscopy) is the gold standard for diagnosing peptic ulcers and should be considered in patients with alarm symptoms or those not responding to empiric therapy.

Patients should be counseled that while gastrointestinal side effects are common with weight loss injections, persistent or severe symptoms always warrant medical evaluation to rule out serious complications and ensure appropriate management. The benefits of weight loss treatment should be balanced against tolerability, and medication adjustments or alternative therapies may be necessary for patients experiencing significant adverse effects.

No, there is no established direct causal link between GLP-1 receptor agonists and peptic ulcer formation. Stomach ulcers are typically caused by Helicobacter pylori infection or chronic NSAID use, and these medications are not listed as causing ulcers in FDA prescribing information.

The most common gastrointestinal side effects include nausea (44%), diarrhea (30%), vomiting (24%), constipation (24%), and abdominal pain (20%). These effects are generally dose-dependent, mild to moderate in severity, and tend to diminish over time as patients develop tolerance.

Seek immediate medical attention for severe persistent abdominal pain, vomiting blood or coffee-ground material, black tarry stools, severe dehydration, or sudden sharp abdominal pain with rigidity. These symptoms may indicate serious complications requiring urgent evaluation.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.