LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

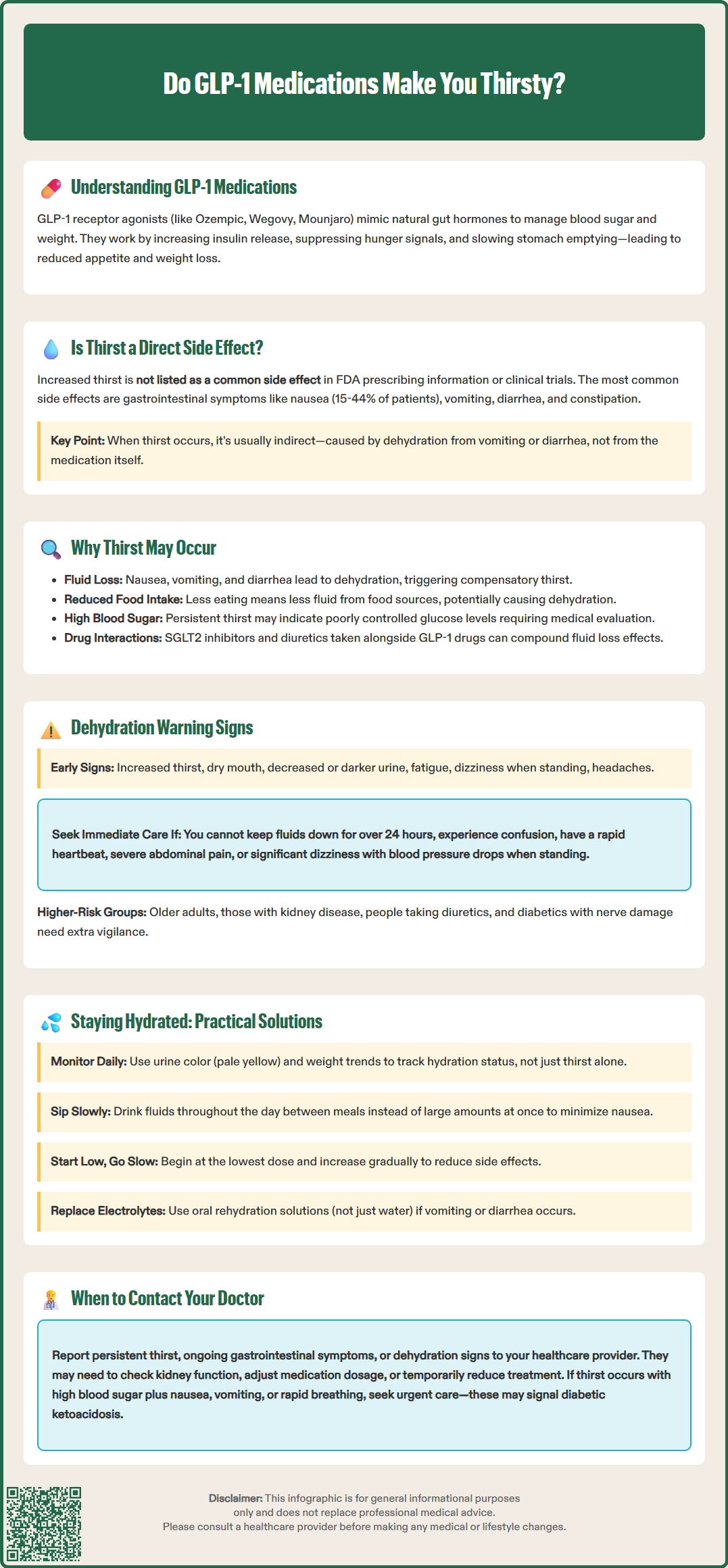

Do GLP-1 medications make you thirsty? Increased thirst is not a common or direct side effect of GLP-1 receptor agonists like semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy), liraglutide (Victoza, Saxenda), or dulaglutide (Trulicity). However, some patients do experience thirst while taking these medications, typically as an indirect consequence of gastrointestinal side effects such as nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea, which can lead to dehydration. Understanding why thirst may occur and how to maintain proper hydration is essential for patients using GLP-1 therapy for type 2 diabetes or weight management. This article explores the relationship between GLP-1 medications and thirst, identifies warning signs of dehydration, and provides practical strategies for staying hydrated during treatment.

Quick Answer: GLP-1 medications do not directly cause increased thirst, but some patients experience it as an indirect consequence of gastrointestinal side effects like vomiting or diarrhea that lead to dehydration.

We offer compounded medications and Zepbound®. Compounded medications are prepared by licensed pharmacies and are not FDA-approved. References to Wegovy®, Ozempic®, Rybelsus®, Mounjaro®, or Saxenda®, or other GLP-1 brands, are informational only. Compounded and FDA-approved medications are not interchangeable.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists represent a class of medications originally developed for type 2 diabetes management and now widely prescribed for chronic weight management. These agents include semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy, Rybelsus), dulaglutide (Trulicity), liraglutide (Victoza, Saxenda), and exenatide (Byetta, Bydureon BCise). Tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Zepbound) works through a dual mechanism as both a GLP-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) receptor agonist. Understanding their mechanisms helps explain potential side effects, including changes in thirst and hydration status.

GLP-1 medications work by mimicking the action of naturally occurring incretin hormones released from the intestine after eating. These drugs bind to GLP-1 receptors throughout the body, triggering multiple physiologic effects. In the pancreas, they enhance glucose-dependent insulin secretion while suppressing glucagon release, improving glycemic control. While the risk of hypoglycemia is generally low with GLP-1 medications alone, this risk increases significantly when combined with insulin or sulfonylureas, often requiring dose adjustments of these agents.

In the brain, GLP-1 receptor activation in appetite-regulating centers reduces hunger and increases satiety, leading to decreased caloric intake and weight loss. Additionally, these medications slow gastric emptying, prolonging the sensation of fullness after meals and contributing to reduced food consumption. This delayed gastric emptying represents one of the primary mechanisms behind the gastrointestinal side effects commonly reported.

Some GLP-1 receptor agonists have demonstrated cardiovascular benefits in specific populations. For example, liraglutide (LEADER trial), injectable semaglutide (SUSTAIN-6), dulaglutide (REWIND), and high-dose semaglutide (SELECT) have shown cardiovascular risk reduction in their respective clinical trials.

Most GLP-1 medications are administered via subcutaneous injection weekly (semaglutide, dulaglutide, exenatide extended-release) or daily (liraglutide), with oral semaglutide (Rybelsus) representing the only currently available oral formulation. The dosing typically follows a gradual titration schedule to minimize gastrointestinal adverse effects, which are the most frequently reported side effects in clinical trials and real-world use.

Increased thirst is not listed as a common adverse effect in the FDA-approved prescribing information for GLP-1 receptor agonists. Clinical trials evaluating these medications have not identified thirst as a frequent or characteristic side effect directly attributable to the pharmacologic action of GLP-1 receptor activation. However, this does not mean patients never experience thirst while taking these medications—the relationship is more nuanced and typically indirect.

The most commonly reported adverse effects in GLP-1 clinical trials include gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea (occurring in 15-44% of patients depending on the specific agent and dose), vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, and abdominal pain. These gastrointestinal effects result from the medications' impact on gastric motility and are generally most pronounced during dose escalation, often improving with continued therapy as tolerance develops.

When patients do report increased thirst while taking GLP-1 medications, it typically occurs as a secondary consequence rather than a direct drug effect. The most common pathway involves dehydration resulting from gastrointestinal side effects, particularly vomiting and diarrhea, which can lead to fluid loss and compensatory thirst. Additionally, patients with diabetes may experience thirst related to inadequate glycemic control, though GLP-1 medications generally improve rather than worsen blood glucose levels.

It is important to distinguish between true polydipsia (excessive thirst with increased urination) and the sensation of dry mouth, which some patients report. For patients with diabetes who experience significant thirst, checking blood glucose levels is essential. If glucose readings are elevated, checking for ketones may be warranted, particularly if accompanied by symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, rapid breathing, or confusion, which could indicate diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) or hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (HHS) requiring urgent medical attention.

Several indirect mechanisms may explain why some individuals experience increased thirst while taking GLP-1 medications, even though thirst is not a direct pharmacologic effect of these agents. Understanding these pathways helps clinicians and patients identify and address the underlying cause rather than attributing the symptom solely to the medication.

Gastrointestinal fluid losses represent the most common reason for thirst in patients taking GLP-1 receptor agonists. Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea—the hallmark side effects of this drug class—can lead to significant fluid depletion. When vomiting or diarrhea occurs, the body loses not only water but also electrolytes, triggering compensatory mechanisms including increased thirst drive. Patients experiencing persistent gastrointestinal symptoms may inadvertently reduce their fluid intake due to nausea, compounding dehydration risk.

Reduced oral intake beyond just fluids may contribute to relative dehydration. The appetite-suppressing effects of GLP-1 medications lead many patients to consume substantially less food and, consequently, less fluid from dietary sources. Foods contribute to daily fluid intake under normal circumstances, so dramatic dietary reduction without compensatory increased beverage consumption can affect hydration status.

Uncontrolled hyperglycemia can cause thirst in patients with diabetes. When blood glucose is elevated, osmotic diuresis occurs, leading to increased urination and compensatory thirst (polydipsia). As GLP-1 therapy improves glucose control, this thirst mechanism should resolve. Patients with persistent thirst despite GLP-1 therapy may need evaluation for inadequate glycemic control.

Concurrent medications should also be considered. Many patients taking GLP-1 receptor agonists also use other medications that may affect fluid balance, including diuretics or SGLT2 inhibitors. SGLT2 inhibitors increase urinary glucose and water excretion and can precipitate euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis, which may present with thirst, nausea, and vomiting even when blood glucose levels are not severely elevated. The combination of medications may have additive effects on hydration status that would not occur with GLP-1 therapy alone.

Dehydration represents a clinically significant risk for patients taking GLP-1 medications, particularly during the initial weeks of therapy or following dose increases when gastrointestinal side effects are most pronounced. Recognizing early warning signs enables timely intervention and prevents progression to more serious complications, including acute kidney injury, which has been reported in postmarketing surveillance of GLP-1 receptor agonists.

Early warning signs of dehydration that patients should monitor include:

Thirst and dry mouth – often the first noticeable symptoms

Decreased urine output – urinating less frequently or producing darker, more concentrated urine

Fatigue and weakness – feeling unusually tired or lacking energy

Dizziness or lightheadedness – particularly when standing (orthostatic symptoms)

Headache – may indicate fluid and electrolyte imbalance

More severe dehydration signs requiring prompt medical attention include:

Persistent vomiting or diarrhea – inability to keep fluids down for more than 24 hours

Significant orthostatic hypotension – marked blood pressure drop upon standing with associated symptoms

Confusion or altered mental status – may indicate severe dehydration or electrolyte disturbance

Decreased skin turgor – skin that remains tented when pinched (though less reliable in older adults)

Rapid heart rate – compensatory tachycardia in response to volume depletion

Patients should also be aware of symptoms that could indicate pancreatitis or gallbladder disease, which have been associated with GLP-1 medications. Severe, persistent abdominal pain, sometimes radiating to the back, with or without vomiting, requires urgent medical evaluation.

Patients at higher risk for dehydration complications include older adults, individuals with chronic kidney disease, those taking diuretics or other medications affecting fluid balance, and patients with diabetes who may have underlying autonomic dysfunction affecting thirst perception. The FDA prescribing information for GLP-1 medications specifically warns about the risk of acute kidney injury, often secondary to dehydration from gastrointestinal adverse effects.

Patients should be counseled to contact their healthcare provider if they experience persistent vomiting, diarrhea, or signs of dehydration that do not improve with increased fluid intake. Severe cases may require temporary discontinuation of the GLP-1 medication, intravenous fluid replacement, and assessment of renal function through serum creatinine and electrolyte measurements.

Proactive hydration strategies can help patients taking GLP-1 receptor agonists maintain adequate fluid balance and minimize thirst-related discomfort. These evidence-based approaches address both prevention and management of hydration challenges associated with GLP-1 therapy.

Establish a hydration routine rather than relying solely on thirst as a guide. Patients should aim for adequate daily fluid intake based on individual needs, activity level, climate, and health status. Rather than focusing on a specific number of cups, patients can monitor hydration status through urine color (pale yellow indicates adequate hydration) and daily weight trends. Setting reminders or using marked water bottles can help ensure consistent intake throughout the day, particularly important since appetite suppression may reduce the natural prompts to drink that accompany eating. Patients with heart failure, advanced kidney disease, or other conditions requiring fluid restrictions should follow their healthcare provider's specific guidance.

Optimize timing of fluid intake around medication administration and meals. Sipping fluids slowly and consistently throughout the day is generally better tolerated than consuming large volumes at once, which may exacerbate nausea. Some patients find that consuming fluids between meals rather than with meals helps manage both hydration and gastrointestinal symptoms. For patients taking oral semaglutide (Rybelsus), specific administration instructions must be followed: take with no more than 4 ounces of plain water on an empty stomach, at least 30 minutes before eating, drinking, or taking other oral medications.

Address gastrointestinal symptoms proactively to prevent dehydration. The American Diabetes Association recommends starting GLP-1 medications at the lowest dose and titrating gradually to minimize side effects. If nausea occurs, eating smaller, more frequent meals, avoiding high-fat foods, and considering antiemetic medications (after consulting with a healthcare provider) may help. For significant vomiting or diarrhea, oral rehydration solutions can help replace both fluids and electrolytes more effectively than water alone.

Monitor hydration status through simple self-assessment techniques. Patients can check urine color and volume, monitor for early dehydration symptoms, and weigh daily at the same time to identify significant fluid losses. Weight changes should be interpreted in context of the expected weight loss from GLP-1 therapy.

Communicate with healthcare providers about persistent thirst or hydration concerns. Patients should report ongoing gastrointestinal symptoms, signs of dehydration, or thirst that seems disproportionate to fluid intake. Healthcare providers may need to assess kidney function, review concurrent medications, evaluate glycemic control in patients with diabetes, or adjust the GLP-1 medication dose or schedule. In some cases, temporary dose reduction or treatment interruption may be appropriate while addressing hydration status, with subsequent cautious re-titration once symptoms resolve.

No, increased thirst is not listed as a common side effect in FDA prescribing information for GLP-1 receptor agonists. When thirst occurs, it is typically an indirect consequence of gastrointestinal side effects like vomiting or diarrhea that cause dehydration.

Early warning signs include thirst, dry mouth, decreased urine output, darker urine, fatigue, dizziness, and headache. Severe signs requiring medical attention include persistent vomiting or diarrhea, confusion, rapid heart rate, and significant lightheadedness when standing.

Establish a consistent hydration routine by sipping fluids throughout the day, monitor urine color for adequate hydration (pale yellow), address gastrointestinal symptoms proactively, and report persistent thirst or dehydration signs to your healthcare provider for evaluation.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.