LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

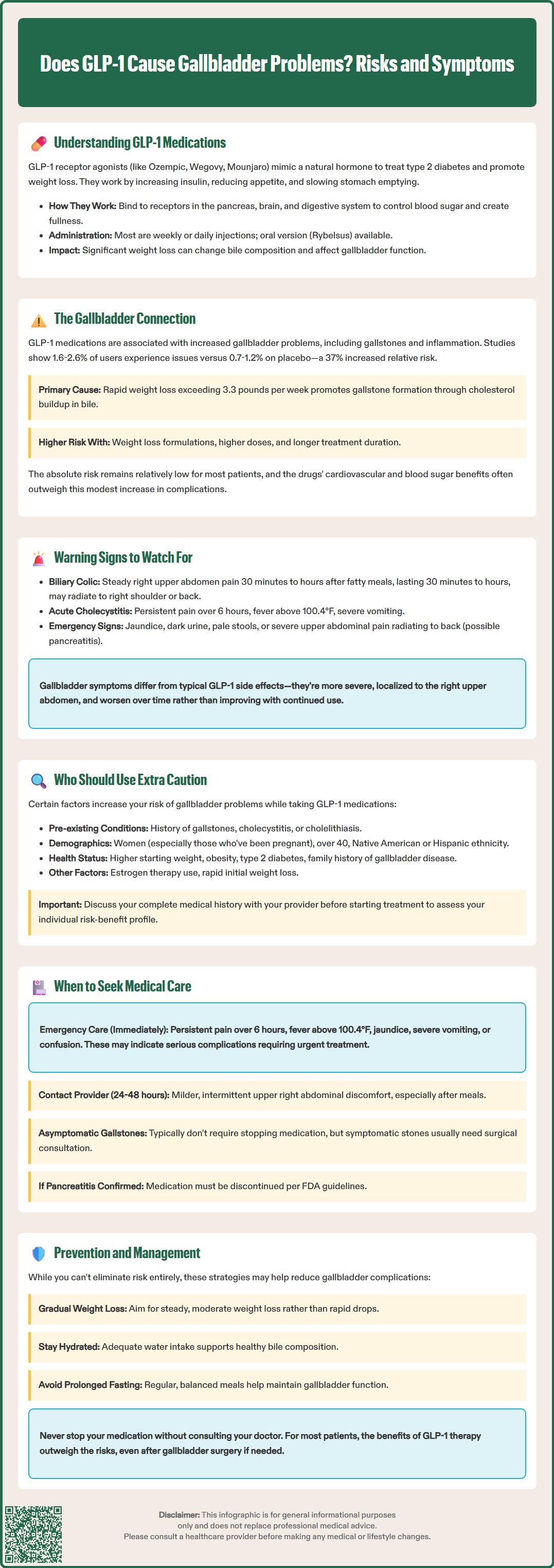

GLP-1 receptor agonists like semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy) and tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Zepbound) have transformed diabetes and weight management, but emerging evidence links these medications to increased gallbladder complications. Clinical trials show higher rates of gallstones and cholecystitis in patients taking GLP-1 drugs compared to placebo, though the absolute risk remains relatively low. Understanding whether these medications directly cause gallbladder problems—or whether rapid weight loss drives the association—is essential for patients and clinicians making treatment decisions. This article examines the evidence, mechanisms, symptoms, and management strategies for gallbladder issues related to GLP-1 therapy.

Quick Answer: GLP-1 receptor agonists are associated with increased risk of gallbladder complications including gallstones and cholecystitis, though the absolute risk remains relatively low for most patients.

We offer compounded medications and Zepbound®. Compounded medications are prepared by licensed pharmacies and are not FDA-approved. References to Wegovy®, Ozempic®, Rybelsus®, Mounjaro®, or Saxenda®, or other GLP-1 brands, are informational only. Compounded and FDA-approved medications are not interchangeable.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists represent a class of medications originally developed for type 2 diabetes management and now widely prescribed for chronic weight management. These drugs include semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy, Rybelsus), liraglutide (Victoza, Saxenda), dulaglutide (Trulicity), and exenatide (Byetta, Bydureon). Tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Zepbound) is a related but distinct dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and GLP-1 receptor agonist. Understanding their mechanism of action helps explain potential adverse effects, including those affecting the gallbladder.

GLP-1 is a naturally occurring incretin hormone released by intestinal cells in response to food intake. GLP-1 receptor agonists mimic this hormone by binding to GLP-1 receptors throughout the body, including the pancreas, brain, stomach, and other organs. In the pancreas, they stimulate glucose-dependent insulin secretion and suppress glucagon release, improving glycemic control. In the brain, they act on satiety centers to reduce appetite and food intake. These medications also slow gastric emptying—the rate at which food leaves the stomach—which contributes to prolonged fullness and reduced caloric intake, though this effect may attenuate over time with long-acting formulations.

The pharmacological effects that make these medications effective for diabetes and weight loss may influence digestive physiology in ways that could affect gallbladder function. The significant weight loss associated with these medications can alter bile composition, while effects on gastrointestinal hormones may influence gallbladder motility. Most GLP-1 medications are administered by subcutaneous injection weekly or daily, though oral semaglutide (Rybelsus) is also available. The FDA has approved these agents based on extensive clinical trial data, but post-marketing surveillance continues to refine our understanding of their safety profile, including gastrointestinal and hepatobiliary effects.

Clinical evidence suggests an association between GLP-1 receptor agonists and dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonists with increased risk of gallbladder-related complications, though the relationship is complex and not fully characterized. The primary concerns include cholelithiasis (gallstones), cholecystitis (gallbladder inflammation), and choledocholithiasis (bile duct stones). Large-scale clinical trials and real-world data have documented higher rates of gallbladder events in patients taking these medications compared to control groups.

The STEP trials evaluating semaglutide 2.4 mg for weight management reported gallbladder disorders in approximately 1.6-2.6% of participants receiving the medication versus 0.7-1.2% receiving placebo. A 2022 systematic review and meta-analysis published in JAMA Internal Medicine found that GLP-1 receptor agonist use was associated with increased risk of biliary disease, with an overall relative risk of approximately 1.37. Notably, the risk appeared higher in trials studying weight loss indications, with higher doses, and with longer duration of treatment. FDA prescribing information for medications like Wegovy (semaglutide) and Mounjaro (tirzepatide) includes warnings that acute gallbladder disease has been reported in clinical trials.

The proposed mechanisms linking these therapies to gallbladder complications include altered gallbladder motility and bile composition changes. Effects on cholecystokinin and other gastrointestinal hormones may influence gallbladder contraction patterns. Rapid weight loss, particularly when exceeding 1.5 kg (3.3 pounds) per week, promotes cholesterol supersaturation in bile and crystal formation. Additionally, caloric restriction and altered fat intake patterns may further compromise gallbladder emptying. While the FDA labels acknowledge reports of acute gallbladder disease, they do not establish definitive causation, and the absolute risk remains relatively low for most patients. It remains challenging to determine whether the medications directly cause gallbladder problems or whether rapid weight loss—a known risk factor for gallstone formation—is the primary driver.

Recognizing gallbladder-related symptoms is essential for patients taking GLP-1 receptor agonists or dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonists, as early identification can prevent serious complications. Gallbladder problems typically manifest with characteristic patterns that differ from the common gastrointestinal side effects of these medications, such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Understanding these distinctions helps patients and clinicians determine when further evaluation is warranted.

Biliary colic, the hallmark symptom of gallstones, presents as episodic right upper quadrant or epigastric pain that typically occurs 30 minutes to several hours after eating, particularly following fatty meals. The pain is usually steady rather than cramping, lasts 30 minutes to several hours, and may radiate to the right shoulder or back. Unlike the transient nausea common with medication initiation or dose escalation, biliary pain is more severe and localized. Patients may also experience nausea and vomiting accompanying the pain episodes.

Acute cholecystitis represents a more serious condition requiring urgent medical attention. Warning signs include:

Persistent right upper quadrant pain lasting more than 6 hours

Fever (temperature above 100.4°F or 38°C)

Severe nausea and vomiting

Jaundice (yellowing of skin or eyes)

Dark urine or pale stools

Tenderness when pressing below the right rib cage

Patients should also be aware that sudden severe epigastric pain radiating to the back, especially when accompanied by vomiting, may indicate pancreatitis, including gallstone-induced pancreatitis. The combination of fever, jaundice, and right upper quadrant pain (Charcot's triad) suggests cholangitis, a medical emergency requiring immediate care.

It is important to distinguish these symptoms from typical medication-related gastrointestinal symptoms. Common medication-related gastrointestinal symptoms usually occur shortly after injection, improve between doses, and gradually diminish with continued use. They are typically diffuse rather than localized to the right upper abdomen. Gallbladder symptoms, conversely, tend to be more severe, localized, and may worsen over time rather than improve. Any patient experiencing persistent right upper quadrant pain, fever, or jaundice should seek prompt medical evaluation regardless of whether they attribute symptoms to their medication.

While GLP-1 receptor agonists and dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonists can benefit many patients with type 2 diabetes or obesity, certain individuals face elevated risk for gallbladder complications and require careful consideration before initiating therapy. Understanding these risk factors enables shared decision-making between patients and healthcare providers, with appropriate monitoring strategies for higher-risk individuals.

Pre-existing gallbladder disease represents a significant consideration. Patients with a history of gallstones, previous cholecystitis, or known cholelithiasis on imaging should discuss these conditions with their healthcare provider before starting therapy. While prior gallbladder disease is not an absolute contraindication, it may influence the risk-benefit assessment. According to current guidelines, asymptomatic gallstones generally do not require intervention, and decisions should be individualized based on symptoms and overall clinical picture.

Rapid weight loss trajectory increases gallstone risk independent of medication choice. Patients losing weight very quickly face higher risk of gallstone formation. This is especially relevant for individuals starting at higher body weights who may experience dramatic initial weight loss. According to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), rapid weight loss is a recognized risk factor for gallstone formation.

Additional risk factors include:

Female sex and pregnancy history: Women, particularly those who have been pregnant, have higher baseline gallstone risk

Age over 40 years: Gallbladder disease incidence increases with age

Obesity: Higher BMI correlates with increased gallstone prevalence

Diabetes: Type 2 diabetes itself is associated with gallbladder dysfunction

Rapid weight cycling: History of repeated weight loss and regain

Certain ethnicities: Native American and Hispanic populations have higher gallstone rates

Family history: Genetic predisposition to gallbladder disease

Estrogen therapy: May increase cholesterol saturation in bile

Patients with multiple risk factors should engage in thorough discussion with their healthcare provider about symptom awareness. The decision to prescribe these medications should weigh the substantial metabolic benefits against individual gallbladder risk, recognizing that for most patients, the cardiovascular and glycemic advantages outweigh the relatively modest absolute risk increase.

Prompt recognition and appropriate response to potential gallbladder symptoms can prevent serious complications in patients taking GLP-1 receptor agonists or dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonists. A systematic approach to symptom evaluation and medical care ensures patient safety while allowing continuation of beneficial therapy when appropriate.

Immediate medical attention is warranted for severe or concerning symptoms. Patients should seek emergency care if they experience persistent right upper quadrant pain lasting more than 6 hours, fever above 100.4°F (38°C), jaundice, severe vomiting preventing oral intake, or signs of sepsis such as confusion or rapid heart rate. These symptoms may indicate acute cholecystitis, choledocholithiasis, or cholangitis—conditions requiring urgent intervention and potentially surgical management. Emergency department evaluation typically includes laboratory testing (complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, liver function tests) and imaging, most commonly right upper quadrant ultrasound, which is the first-line imaging modality according to American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria.

Non-urgent evaluation is appropriate for milder, intermittent symptoms. Patients experiencing episodic right upper quadrant discomfort, particularly after meals, should contact their healthcare provider within 24-48 hours. The provider will determine whether the medication should be temporarily held pending evaluation, based on clinical judgment and in accordance with FDA prescribing information. Initial assessment typically includes physical examination, laboratory studies, and abdominal ultrasound—the first-line imaging modality for gallbladder disease with sensitivity of approximately 84-89% for cholelithiasis.

Management decisions depend on findings and symptom severity. Asymptomatic gallstones discovered incidentally generally do not require intervention, and therapy may continue with patient education about warning symptoms. Symptomatic cholelithiasis typically warrants surgical consultation for cholecystectomy, which can often be performed laparoscopically. The timing of surgery and whether to continue therapy during the interim requires individualized decision-making. Importantly, confirmed acute pancreatitis is a reason to discontinue therapy per FDA prescribing information.

Preventive strategies may theoretically reduce risk, though evidence is limited. Maintaining gradual rather than precipitous weight loss, ensuring adequate hydration, and avoiding prolonged fasting may help, but these approaches have not been specifically validated in patients taking these medications. Ursodeoxycholic acid, a bile acid that reduces cholesterol saturation, has been studied for gallstone prevention during rapid weight loss, but is not routinely recommended. Patients should maintain open communication with their healthcare team, report new symptoms promptly, and never discontinue prescribed medications without medical guidance. For many patients, the substantial benefits of therapy for diabetes control and weight management justify continued use even after gallbladder issues are addressed surgically.

Clinical trials report gallbladder disorders in approximately 1.6-2.6% of patients taking semaglutide for weight loss compared to 0.7-1.2% receiving placebo. Meta-analyses show an overall relative risk increase of about 1.37-fold, with higher risk at higher doses and longer treatment duration.

Treatment decisions depend on symptom severity and individual circumstances. Asymptomatic gallstones discovered incidentally may not require stopping medication, while symptomatic gallstones typically warrant surgical consultation for cholecystectomy. Always consult your healthcare provider before discontinuing prescribed medications.

Seek immediate medical attention for persistent right upper quadrant pain lasting more than 6 hours, fever above 100.4°F, jaundice (yellowing of skin or eyes), severe vomiting, or signs of infection. These may indicate acute cholecystitis, bile duct obstruction, or cholangitis requiring urgent intervention.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.