LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

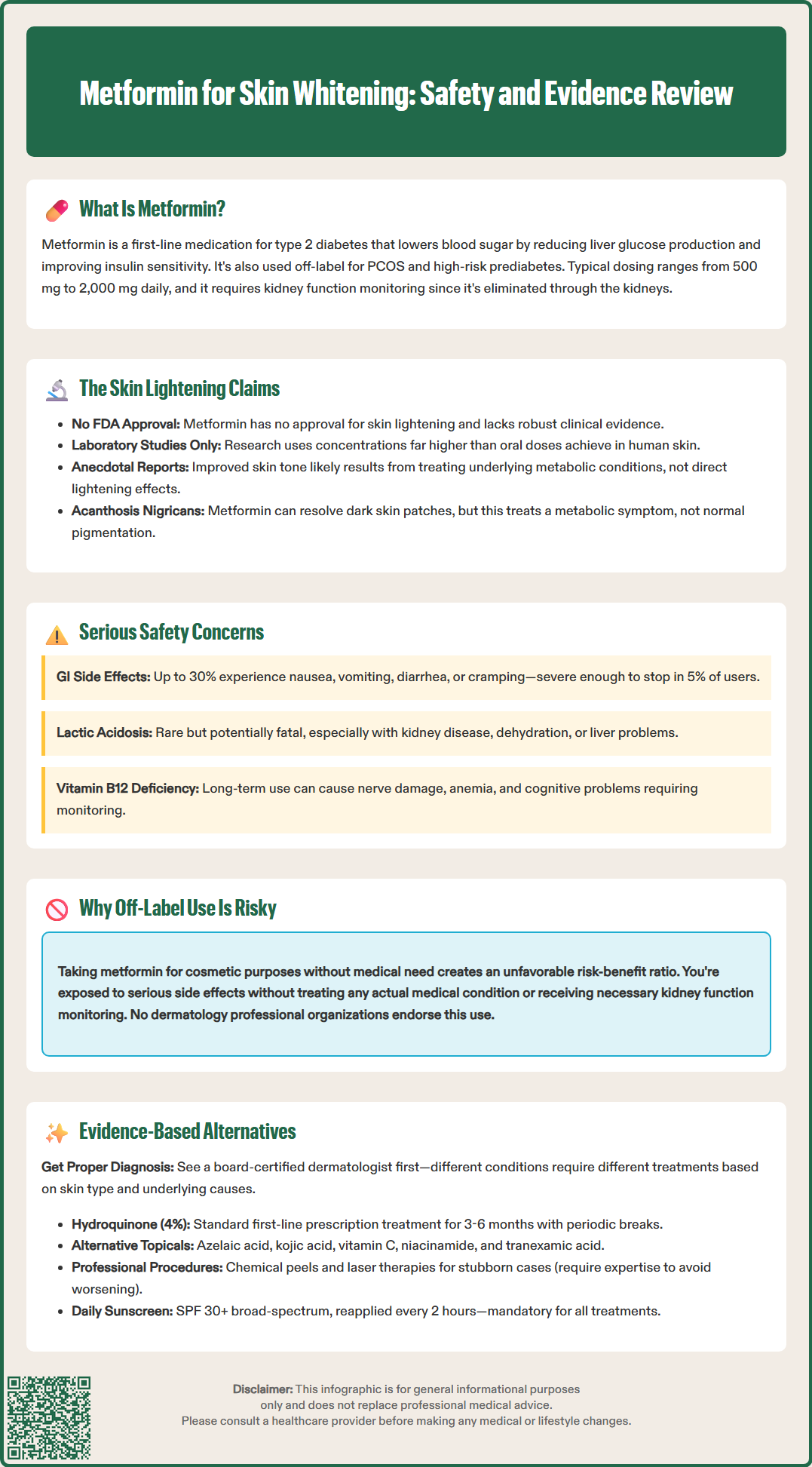

Metformin for skin whitening has emerged as an unproven claim circulating online, despite the medication's established role as a first-line therapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus. The FDA has not approved metformin for any dermatologic or cosmetic indication, and no clinical practice guidelines from the American Academy of Dermatology support this use. While metformin addresses insulin resistance and may improve acanthosis nigricans—a condition causing darkened skin patches—this represents treatment of an underlying metabolic disorder rather than cosmetic skin lightening. Using prescription diabetes medications without legitimate medical indication carries significant safety risks, including gastrointestinal distress and rare but serious complications like lactic acidosis. Patients seeking treatment for hyperpigmentation should consult board-certified dermatologists for evidence-based therapies.

Quick Answer: Metformin is not FDA-approved for skin whitening and lacks clinical evidence supporting this cosmetic use.

Metformin is an oral antihyperglycemic agent in the biguanide class, primarily prescribed for the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus. The FDA first approved metformin in 1994, and it remains a cornerstone pharmacologic therapy for glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes. Current American Diabetes Association (ADA) guidelines recommend individualizing initial therapy based on comorbidities, with metformin often used as first-line therapy but sometimes preceded by GLP-1 receptor agonists or SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with established cardiovascular or kidney disease.

The medication works through several complementary mechanisms of action. Metformin decreases hepatic glucose production by inhibiting gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis in the liver. It also enhances insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues, particularly skeletal muscle, improving glucose uptake and utilization. Additionally, metformin reduces intestinal absorption of glucose. These combined effects lower both fasting and postprandial blood glucose levels without causing hypoglycemia when used as monotherapy.

Metformin is commonly prescribed off-label for polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), where it addresses insulin resistance that contributes to hormonal imbalances, irregular menstruation, and metabolic complications. While metformin is not FDA-approved for prediabetes prevention, the ADA suggests considering it for high-risk individuals with prediabetes, particularly those with BMI ≥35 kg/m², those under 60 years of age, and women with prior gestational diabetes.

Metformin is available in immediate-release and extended-release formulations, with typical dosing ranging from 500 mg to 2,000 mg daily, divided or taken once daily depending on the formulation. The medication requires dose adjustment in patients with reduced kidney function, as metformin is eliminated unchanged through renal excretion. Metformin is contraindicated in patients with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) below 30 mL/min/1.73 m², should not be initiated in those with eGFR 30-45 mL/min/1.73 m², and requires risk-benefit reassessment if eGFR falls below 45 mL/min/1.73 m² during treatment.

There is no FDA-approved indication for metformin as a skin lightening or depigmentation agent, and robust clinical evidence supporting this use remains absent. The notion that metformin might lighten skin tone appears to stem from anecdotal reports and limited preliminary research rather than established dermatologic practice. Some proponents suggest that metformin's effects on insulin signaling and cellular metabolism could theoretically influence melanin production, but this hypothesis lacks substantiation through rigorous clinical trials.

A small number of in vitro studies have explored metformin's potential effects on melanocytes, the cells responsible for producing melanin pigment. These laboratory investigations suggest that metformin may activate AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathways, which could theoretically modulate melanogenesis. However, in vitro findings do not reliably translate to clinical outcomes in human skin, and the concentrations used in laboratory settings often far exceed what would be achieved through oral administration in patients.

Some individuals have reported subjective improvements in skin tone while taking metformin for diabetes or PCOS, but these observations are confounded by multiple variables. Improvements in insulin resistance, hormonal balance, and inflammatory markers associated with metabolic conditions may indirectly affect skin appearance, including reduction of acanthosis nigricans—a condition characterized by dark, velvety skin patches often associated with insulin resistance. However, resolution of acanthosis nigricans represents treatment of an underlying metabolic disorder rather than a lightening effect on normal skin.

The American Academy of Dermatology and other dermatology professional organizations have not endorsed metformin for cosmetic skin lightening, and no clinical practice guidelines recommend this application. Using prescription medications without a legitimate medical indication is potentially unsafe and inappropriate. Patients seeking skin tone modification should consult board-certified dermatologists who can provide evidence-based treatments tailored to specific dermatologic diagnoses rather than pursuing unproven off-label uses of diabetes medications.

Using metformin without appropriate medical indication and supervision carries significant safety risks that outweigh any unproven cosmetic benefits. The most common adverse effects of metformin involve the gastrointestinal system, affecting up to 30% of users. These include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal cramping, and metallic taste. Gastrointestinal symptoms often improve with dose titration and use of extended-release formulations, but they can be severe enough to necessitate discontinuation in approximately 5% of patients.

The most serious risk associated with metformin is lactic acidosis, a rare but potentially fatal complication occurring in approximately 3 to 10 cases per 100,000 patient-years. Lactic acidosis develops when metformin accumulates in the body, typically due to impaired renal function, leading to dangerous buildup of lactate. Risk factors include kidney disease, sepsis, hypoxemia, dehydration, hepatic impairment, excessive alcohol consumption, and acute or unstable heart failure. Symptoms of lactic acidosis include muscle pain, respiratory distress, severe fatigue, and altered mental status, requiring immediate emergency medical attention.

Long-term metformin use can lead to vitamin B12 deficiency in some patients, potentially causing peripheral neuropathy, anemia, and cognitive changes. The mechanism involves impaired calcium-dependent absorption of the vitamin B12-intrinsic factor complex in the terminal ileum. The ADA recommends periodic assessment of vitamin B12 levels, especially in patients with anemia or peripheral neuropathy.

Metformin should be temporarily discontinued at the time of or prior to procedures involving iodinated contrast media in patients with eGFR 30-60 mL/min/1.73 m² or other risk factors for acute kidney injury. It should also be held during acute illness or major surgery, and restarted only when renal function is stable.

For individuals without diabetes or insulin resistance taking metformin for unproven cosmetic purposes, the risk-benefit ratio is unfavorable. These patients expose themselves to medication side effects and potential serious complications without addressing any underlying medical condition. Furthermore, metformin requires baseline and periodic monitoring of kidney function—medical oversight that may be absent when the drug is obtained through inappropriate channels or used without physician supervision.

Patients concerned about skin hyperpigmentation have access to numerous evidence-based treatments with established safety and efficacy profiles. The first step involves accurate diagnosis by a board-certified dermatologist, as various conditions cause skin darkening, including melasma, post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, solar lentigines, and acanthosis nigricans. Treatment selection depends on the specific diagnosis, skin type, and underlying contributing factors.

Topical therapies represent the first-line approach for most hyperpigmentation disorders. Hydroquinone is a standard depigmenting agent, available by prescription only in the United States (typically 4% strength). Hydroquinone inhibits tyrosinase, the rate-limiting enzyme in melanin synthesis. Treatment typically continues for 3 to 6 months under dermatologic supervision, with periodic breaks to minimize risk of ochronosis (paradoxical darkening). Triple combination cream (fluocinolone 0.01%, hydroquinone 4%, tretinoin 0.05%; Tri-Luma) is FDA-approved for short-term treatment (up to 8 weeks) of facial melasma. Prolonged use of this combination should be avoided due to risks associated with chronic topical corticosteroid application.

Alternative topical agents include azelaic acid (15% to 20%), which inhibits tyrosinase and provides anti-inflammatory effects with an excellent safety profile suitable for long-term use. Kojic acid, vitamin C (L-ascorbic acid), niacinamide, and tranexamic acid offer additional options with varying mechanisms of action. Topical tranexamic acid has fewer safety concerns than oral formulations. Retinoids (tretinoin, adapalene) enhance epidermal turnover and can improve hyperpigmentation when combined with other agents.

Procedural interventions provide options for refractory cases. Chemical peels using glycolic acid, salicylic acid, or trichloroacetic acid remove pigmented epidermal layers. Laser and light-based therapies, including Q-switched lasers, intense pulsed light (IPL), and fractional lasers, target melanin or stimulate collagen remodeling. These procedures require expertise in treating diverse skin types to avoid post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Oral tranexamic acid is sometimes used off-label for melasma but carries thromboembolic risks and is contraindicated in patients with active or history of thrombosis, requiring careful patient selection and monitoring.

Photoprotection with broad-spectrum sunscreen (SPF 30 or higher) is essential for all hyperpigmentation treatments, as ultraviolet radiation stimulates melanogenesis and can reverse therapeutic gains. Patients should apply sunscreen daily and reapply every two hours during sun exposure. Addressing underlying conditions—such as hormonal imbalances, inflammatory skin diseases, or metabolic disorders—is crucial for optimal outcomes and prevention of recurrence.

No, metformin is not FDA-approved for skin lightening or any dermatologic indication. It is approved only for managing type 2 diabetes mellitus, and no clinical evidence supports its use for cosmetic skin whitening.

Using metformin without medical indication exposes patients to gastrointestinal side effects, rare but potentially fatal lactic acidosis, vitamin B12 deficiency, and requires kidney function monitoring that may be absent without physician supervision.

Evidence-based treatments include prescription topical hydroquinone, azelaic acid, tretinoin, triple combination cream for melasma, chemical peels, and laser therapies, all requiring diagnosis and supervision by a board-certified dermatologist.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.