LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

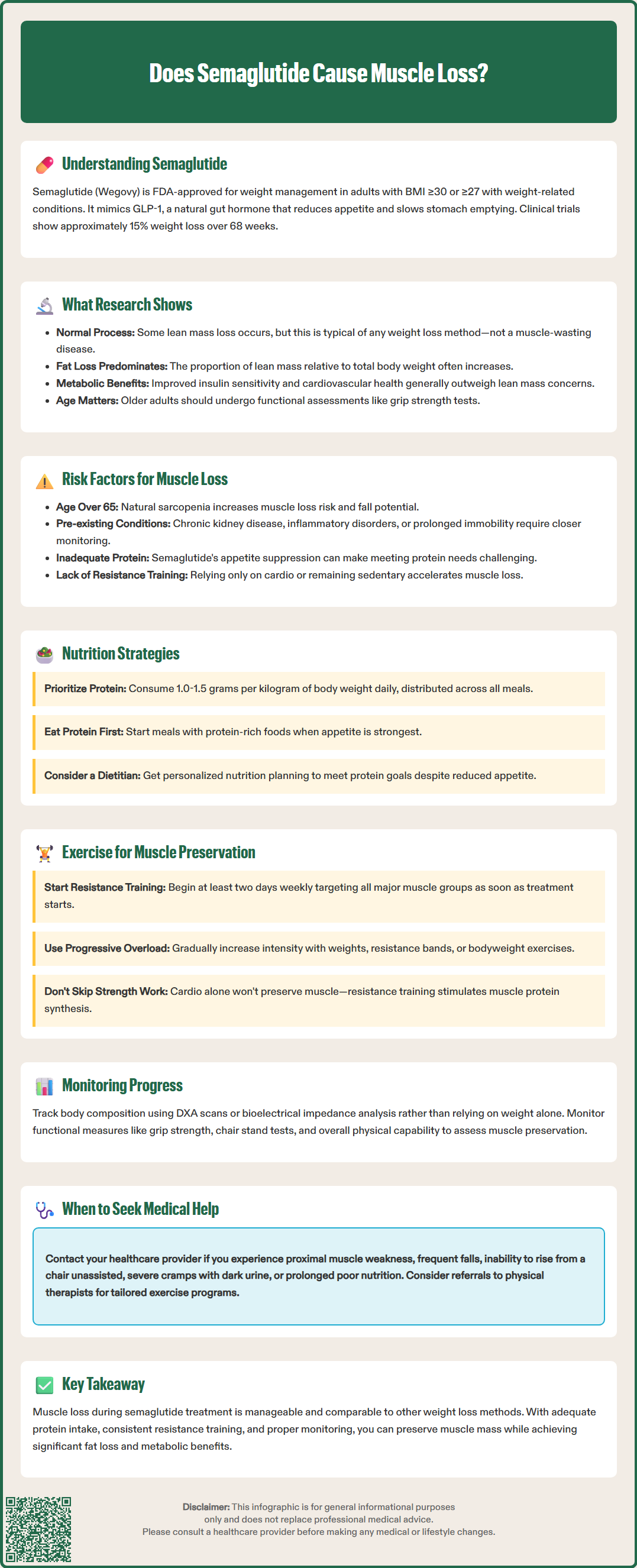

Does semaglutide cause muscle loss? This question concerns many patients considering or currently using this GLP-1 receptor agonist for weight management or type 2 diabetes. Semaglutide (Wegovy for weight management, Ozempic for diabetes) produces significant weight reduction, but like all substantial weight loss, it includes some lean body mass reduction alongside fat loss. Understanding the mechanisms behind this muscle loss, the factors that influence it, and evidence-based strategies to preserve muscle function helps patients and clinicians optimize treatment outcomes while maintaining strength and functional independence throughout therapy.

Quick Answer: Semaglutide causes some muscle loss as part of overall weight reduction, but this occurs through caloric deficit rather than direct muscle-wasting mechanisms.

Semaglutide is a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist approved by the FDA for type 2 diabetes management (under the brand name Ozempic) and chronic weight management (as Wegovy). Wegovy is specifically indicated for adults with a BMI ≥30 kg/m² or ≥27 kg/m² with at least one weight-related comorbidity. Importantly, while Ozempic may result in weight loss, it is not FDA-approved for weight management.

This medication mimics the action of endogenous GLP-1, a hormone released from the intestine in response to food intake. By binding to GLP-1 receptors in multiple tissues, semaglutide enhances glucose-dependent insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells, suppresses inappropriate glucagon release, and slows gastric emptying, though this gastric-slowing effect tends to attenuate over time.

The weight loss effects of semaglutide occur primarily through central nervous system pathways. The medication acts on appetite-regulating centers in the hypothalamus, reducing hunger signals and increasing satiety after meals. Clinical trials have demonstrated substantial weight reduction, with patients losing an average of approximately 15% of their initial body weight over 68 weeks in the STEP-1 trial program with semaglutide 2.4 mg.

It is important to recognize that semaglutide does not selectively target fat tissue. When the body experiences a caloric deficit—whether induced pharmacologically or through dietary restriction alone—weight loss typically includes both fat mass and fat-free mass (which comprises muscle, bone, organs, and water). The proportion of muscle loss relative to total weight loss becomes a critical consideration for patients and clinicians, particularly in older adults or those with limited baseline muscle mass. Understanding this physiological reality helps frame appropriate expectations and guides strategies to optimize body composition during treatment.

Current evidence indicates that semaglutide treatment is associated with some degree of lean body mass reduction, though this occurs as part of overall weight loss rather than through a direct muscle-wasting mechanism. There is no official link between semaglutide and a specific myopathy or muscle-degrading process. Instead, the muscle loss observed reflects the general physiological response to weight reduction.

Analysis of the STEP clinical trials reveals that lean body mass typically accounts for a portion of total weight lost during semaglutide treatment. Body composition substudies using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) have shown that while patients lost significant total weight, lean mass decreased proportionally less than fat mass. Importantly, while absolute lean mass decreases, the proportion of lean mass relative to total body weight often increases because fat loss predominates.

The absolute amount of muscle loss correlates with the magnitude of total weight reduction. Patients who lose more weight will inevitably lose more lean mass in absolute terms, even if the percentage remains consistent. Research has not identified semaglutide as causing disproportionate muscle wasting compared to equivalent weight loss achieved through other methods.

Clinicians should counsel patients that some lean mass reduction is an expected component of significant weight loss, but this does not indicate a pathological process. The metabolic benefits of fat mass reduction, including improved insulin sensitivity and cardiovascular risk profile, generally outweigh concerns about proportional lean mass loss in patients with obesity. However, in older adults or those with sarcopenia, functional assessment (using tools like grip strength measurement or the SARC-F questionnaire) is warranted to identify patients who may need additional intervention to preserve muscle function.

Multiple patient-specific and behavioral factors determine the extent of muscle loss during semaglutide therapy. Age represents a significant variable, as older adults naturally experience sarcopenia (age-related muscle loss) and may have reduced capacity for muscle protein synthesis. Patients over 65 years require particular attention to muscle preservation, as excessive lean mass loss can impair functional independence and increase fall risk.

Baseline body composition also matters considerably. Individuals with higher initial muscle mass relative to fat mass may experience greater absolute lean tissue loss, while those with severe obesity and limited muscle mass face different risks. Patients with pre-existing conditions affecting muscle health—such as chronic kidney disease, inflammatory disorders, or previous prolonged immobility—warrant closer monitoring.

Dietary protein intake during weight loss critically influences muscle preservation. Inadequate protein consumption, particularly when combined with severe caloric restriction, accelerates muscle catabolism. Evidence suggests that 1.0-1.5 grams of protein per kilogram of adjusted body weight daily may help preserve muscle during weight loss, though targets should be individualized. Patients with chronic kidney disease should not increase protein intake without medical guidance. Many patients on semaglutide experience reduced appetite and early satiety, which can inadvertently lead to insufficient protein intake if not addressed proactively.

Physical activity patterns represent perhaps the most modifiable factor. Resistance training provides a powerful stimulus for muscle protein synthesis and can substantially mitigate lean mass loss during caloric deficit. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Physical Activity Guidelines recommend muscle-strengthening activities at least twice weekly. Conversely, sedentary patients or those engaging only in cardiovascular exercise without resistance components will experience greater muscle loss. The rate of weight loss also influences outcomes—generally, more gradual weight reduction (approximately 1-2 pounds weekly) may help preserve lean mass.

Concurrent medications may affect muscle metabolism. Chronic glucocorticoid use, certain medications with myopathy as a rare side effect (such as statins or fluoroquinolones), and systemic illnesses can promote muscle catabolism. Clinicians should review medication lists and consider potential interactions when assessing muscle loss risk in patients initiating semaglutide.

Evidence-based strategies can significantly reduce muscle loss during semaglutide treatment. Prioritizing adequate protein intake stands as the foundational intervention. Most patients should aim for 1.0-1.5 grams of protein per kilogram of adjusted body weight daily, distributed across meals to optimize muscle protein synthesis. Patients with kidney or liver disease should consult their healthcare provider before increasing protein intake. Practical approaches include consuming protein-rich foods at each meal (lean meats, fish, eggs, dairy, legumes) and considering protein supplementation if appetite limitations make whole-food targets difficult to achieve. Given semaglutide's appetite-suppressing effects, patients may benefit from consuming protein early in meals when hunger is greatest.

Resistance training provides the most effective stimulus for muscle preservation during weight loss. The U.S. Physical Activity Guidelines recommend muscle-strengthening activities at least two days weekly targeting all major muscle groups, with progressive overload (gradually increasing weight or resistance) as tolerated. Even modest resistance training—using body weight, resistance bands, or light weights—demonstrates benefit. Patients should be encouraged to begin or continue strength training concurrent with semaglutide initiation rather than waiting until significant weight loss has occurred. For older adults or those with mobility limitations, physical therapy referral may facilitate safe, appropriate exercise prescription.

Monitoring body composition, rather than weight alone, allows for more nuanced assessment of treatment effects. While dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) provides detailed body composition analysis, it may not be readily accessible or covered by insurance in all clinical settings. Bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA), though less precise and affected by hydration status, offers a practical alternative for tracking trends. Functional assessments—such as grip strength measurement, timed up-and-go tests, or chair stand tests—provide clinically meaningful data about muscle function and can identify patients requiring intervention.

Patients should be advised to seek medical evaluation for concerning symptoms such as new or progressive proximal weakness, frequent falls, inability to rise from a chair without assistance, severe muscle cramps with dark urine, or prolonged poor nutritional intake. Semaglutide dosing should follow FDA-approved titration schedules, with adjustments made primarily for gastrointestinal tolerability rather than muscle preservation specifically. Referral to registered dietitians with expertise in weight management can optimize nutritional strategies, while physical therapists or exercise physiologists can design individualized resistance training programs. Regular follow-up visits should include discussion of protein intake, exercise adherence, and functional status, with adjustments to the treatment plan as needed to balance weight loss goals with muscle preservation.

Muscle loss during semaglutide treatment is not necessarily permanent. With resistance training and adequate protein intake, patients can rebuild muscle mass, though this requires consistent effort and appropriate exercise programming.

The amount of muscle loss varies by individual and correlates with total weight reduction. Body composition studies show lean mass decreases proportionally less than fat mass, with the ratio influenced by protein intake, resistance training, age, and baseline body composition.

Older adults should not necessarily avoid semaglutide, but they require closer monitoring with functional assessments and proactive muscle preservation strategies including resistance training and adequate protein intake. The metabolic benefits may outweigh risks when muscle preservation is actively addressed.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.