LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

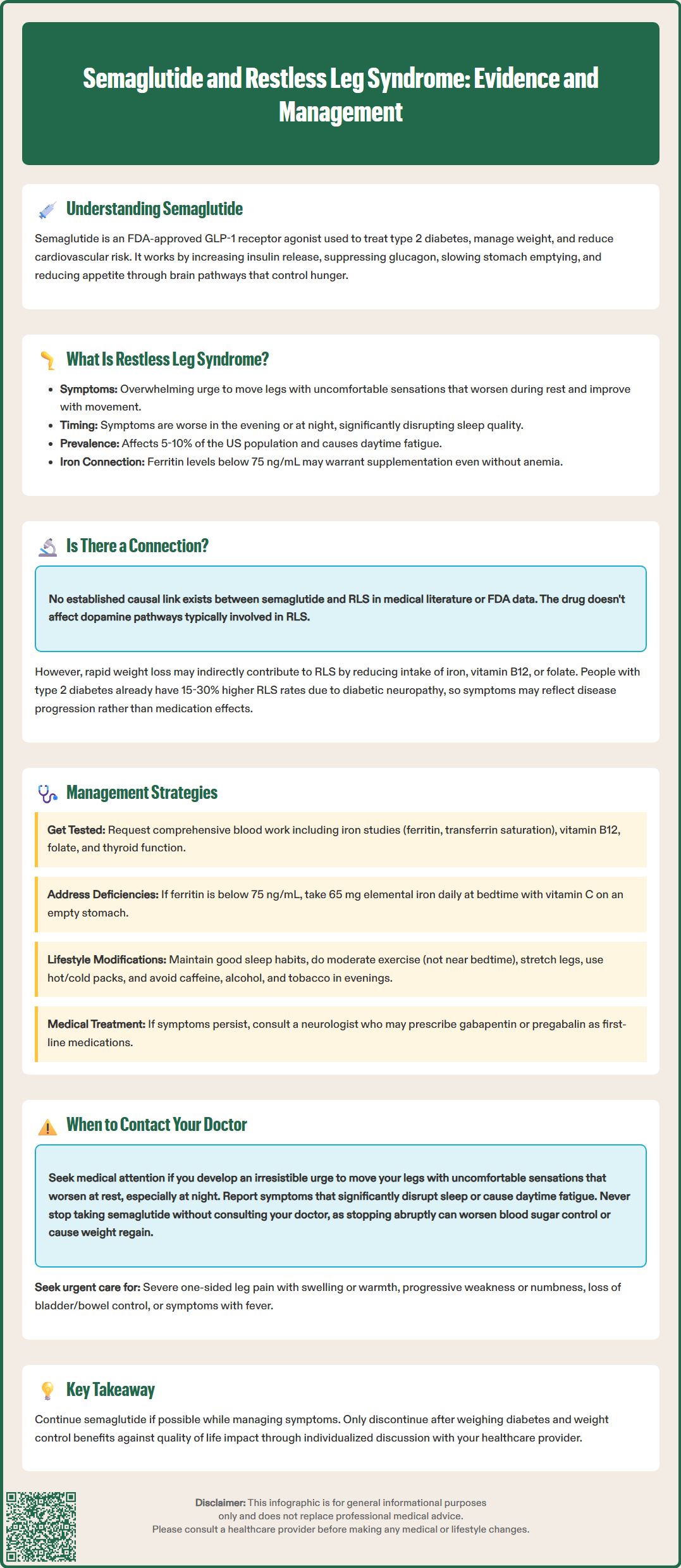

Semaglutide, marketed as Ozempic, Rybelsus, and Wegovy, is an FDA-approved GLP-1 receptor agonist used for type 2 diabetes, chronic weight management, and cardiovascular risk reduction. While this medication has transformed metabolic disease treatment, patients occasionally report new neurological symptoms during therapy, including restless leg syndrome. Currently, no established link exists between semaglutide and restless leg syndrome in medical literature or FDA labeling. However, understanding potential indirect connections—such as nutritional changes from rapid weight loss or the elevated baseline RLS risk in diabetic populations—helps clinicians provide comprehensive patient care and appropriate symptom evaluation.

Quick Answer: No established causal relationship exists between semaglutide and restless leg syndrome based on current FDA labeling and medical literature.

Semaglutide is a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist approved by the FDA for three primary indications: type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic weight management, and cardiovascular risk reduction in adults with obesity/overweight and established cardiovascular disease. Marketed under brand names including Ozempic and Rybelsus for diabetes, and Wegovy for weight management and cardiovascular risk reduction, semaglutide works by mimicking the action of the naturally occurring hormone GLP-1.

The medication's mechanism of action involves multiple pathways that contribute to glycemic control and weight reduction. Semaglutide enhances glucose-dependent insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells, suppresses inappropriately elevated glucagon secretion, and slows gastric emptying. These effects collectively improve blood sugar control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Additionally, semaglutide acts on appetite-regulating centers in the brain, promoting satiety and reducing caloric intake, which facilitates weight loss.

Semaglutide carries a boxed warning for risk of thyroid C-cell tumors and is contraindicated in patients with a personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) or Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia syndrome type 2 (MEN2). Common adverse effects include gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation, which typically diminish over time. More serious risks include pancreatitis, gallbladder disease (cholelithiasis, cholecystitis), diabetic retinopathy complications (particularly with rapid improvement in glucose control), and acute kidney injury due to dehydration from gastrointestinal side effects. When used with insulin or sulfonylureas, dose adjustments of these medications may be needed to reduce hypoglycemia risk.

Semaglutide is administered either as a once-weekly subcutaneous injection or as a daily oral tablet. The choice between formulations should be individualized based on patient preferences, clinical factors, and treatment goals. Dosing is typically initiated at a low level and gradually titrated upward to minimize gastrointestinal side effects and improve tolerability. Semaglutide is not indicated for the treatment of type 1 diabetes.

Restless leg syndrome (RLS), also known as Willis-Ekbom disease, is a neurological sensorimotor disorder characterized by an overwhelming urge to move the legs, typically accompanied by uncomfortable sensations. The condition affects approximately 5-10% of the US population, with varying degrees of severity. RLS significantly impacts quality of life, particularly through sleep disruption and daytime fatigue.

The hallmark features of RLS include four essential diagnostic criteria established by the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group. First, patients experience an urge to move the legs, usually accompanied by uncomfortable sensations described as crawling, tingling, burning, or aching deep within the leg muscles. Second, symptoms begin or worsen during periods of rest or inactivity. Third, movement provides partial or complete relief of symptoms, at least temporarily. Fourth, symptoms follow a circadian pattern, being worse in the evening or at night.

RLS can be classified as either primary (idiopathic) or secondary to underlying conditions. Primary RLS often has a genetic component, with approximately 50% of cases showing familial clustering. Secondary RLS may result from iron deficiency, end-stage renal disease, pregnancy, peripheral neuropathy, or certain medications. Common pharmacological triggers include antihistamines, antidopaminergic antiemetics, most antidepressants (particularly selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants), and some antipsychotic medications. Some antidepressants like bupropion may have neutral or beneficial effects on RLS symptoms.

The pathophysiology of RLS involves dopaminergic dysfunction in the central nervous system and abnormalities in brain iron metabolism. Diagnostic evaluation should include assessment of serum ferritin levels and transferrin saturation, as iron deficiency is a treatable contributing factor. A fasting morning ferritin level below 75 ng/mL (with consideration of C-reactive protein, as ferritin is an acute phase reactant) may warrant iron supplementation even in the absence of anemia, as brain iron stores may be depleted despite normal peripheral iron indices.

Currently, there is no established causal relationship between semaglutide and restless leg syndrome in the medical literature or FDA prescribing information. Semaglutide is not listed among the medications known to trigger or exacerbate RLS, and the drug's mechanism of action does not directly involve dopaminergic pathways typically implicated in RLS pathophysiology. However, the absence of documented cases does not definitively exclude the possibility of an association, particularly given the relatively recent widespread use of semaglutide.

Several indirect mechanisms could theoretically link semaglutide use to RLS symptoms, though these remain entirely speculative. Rapid weight loss associated with semaglutide therapy may lead to reduced intake of nutrients, including iron, vitamin B12, or folate, which are recognized risk factors for secondary RLS. While semaglutide does slow gastric emptying, there is limited evidence that this leads to clinically significant nutrient malabsorption in most patients. Additionally, significant weight loss may unmask previously subclinical RLS or alter the severity of existing symptoms.

Patients with type 2 diabetes have an elevated baseline risk of RLS compared to the general population, with prevalence estimates ranging from 15-30% in diabetic cohorts. This increased risk is attributed to diabetic peripheral neuropathy, which shares overlapping symptoms with RLS and may complicate diagnosis. Therefore, RLS symptoms emerging during semaglutide treatment may represent the natural progression of diabetic complications rather than a drug-induced effect.

Clinicians should maintain awareness that correlation does not imply causation. If a patient develops RLS symptoms after initiating semaglutide, a comprehensive evaluation for alternative explanations is warranted before attributing symptoms to the medication. This includes assessment for nutritional deficiencies, progression of diabetic neuropathy, introduction of other medications, or development of comorbid conditions known to cause secondary RLS.

For patients experiencing restless leg symptoms while taking semaglutide, a systematic approach to evaluation and management is essential. Initial assessment should focus on identifying and addressing reversible contributing factors before considering medication discontinuation. Laboratory evaluation should include a fasting morning complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, serum ferritin, transferrin saturation, iron studies, C-reactive protein, vitamin B12, and folate levels. Thyroid function tests and hemoglobin A1c should also be reviewed, as both thyroid disorders and poorly controlled diabetes can contribute to neuropathic symptoms.

If iron deficiency is identified (ferritin <75 ng/mL and/or transferrin saturation <20%), iron supplementation represents a first-line intervention that may significantly improve or resolve RLS symptoms. Oral iron supplementation with 65 mg of elemental iron (e.g., ferrous sulfate 325 mg) daily or every other day, taken with vitamin C to enhance absorption and on an empty stomach when tolerated, is typically recommended. Iron should be taken at bedtime, away from calcium supplements and proton pump inhibitors. For patients with gastrointestinal intolerance, inadequate response to oral therapy, or ferritin 75-100 ng/mL with low transferrin saturation, intravenous iron (such as ferric carboxymaltose) may be considered. Improvement in RLS symptoms may take several weeks to months following iron repletion.

Non-pharmacological interventions should be emphasized as initial management strategies. These include maintaining good sleep hygiene, engaging in moderate regular exercise (avoiding intense exercise close to bedtime), performing leg stretches or massage, applying hot or cold packs to the legs, and practicing relaxation techniques. Patients should be advised to avoid potential triggers such as caffeine, alcohol, and tobacco, particularly in the evening hours. Maintaining adequate hydration and ensuring balanced nutrition despite reduced appetite from semaglutide is important.

If symptoms persist despite addressing nutritional deficiencies and implementing lifestyle modifications, consultation with a neurologist or sleep medicine specialist may be appropriate. Current guidelines recommend alpha-2-delta calcium channel ligands (gabapentin, pregabalin, or FDA-approved gabapentin enacarbil) as first-line pharmacological treatment. Dopamine agonists (FDA-approved pramipexole, ropinirole, or rotigotine) are effective but carry risks of augmentation (paradoxical worsening of symptoms) and impulse control disorders with long-term use. Low-dose opioids may be considered in severe refractory cases under specialist supervision. The decision to continue or discontinue semaglutide should be individualized, weighing the benefits of glycemic control and weight management against the impact of RLS symptoms on quality of life.

Patients taking semaglutide should contact their healthcare provider if they develop new or worsening symptoms suggestive of restless leg syndrome, particularly if these symptoms significantly impact sleep quality or daily functioning. While RLS is not a recognized adverse effect of semaglutide, any new neurological symptoms warrant medical evaluation to ensure appropriate diagnosis and exclude other potentially serious conditions.

Specific symptoms that should prompt medical consultation include an irresistible urge to move the legs, especially when accompanied by uncomfortable sensations such as crawling, pulling, tingling, or aching deep within the leg muscles. Patients should report if these symptoms worsen during rest or inactivity, improve with movement, and follow a pattern of being worse in the evening or nighttime hours. Additionally, any symptoms that interfere with the ability to fall asleep or stay asleep, leading to significant daytime fatigue or impaired concentration, require professional assessment.

Urgent medical attention is warranted for certain red flag symptoms that may indicate conditions other than RLS. These include sudden onset of severe leg pain, particularly if unilateral and associated with swelling or warmth (which could suggest deep vein thrombosis), progressive weakness or numbness in the legs, loss of bladder or bowel control, or symptoms accompanied by fever or signs of infection. Patients taking dopamine agonists for RLS should report any sudden worsening of symptoms or earlier onset during the day, which may indicate augmentation requiring medication adjustment.

Patients should not discontinue semaglutide without consulting their healthcare provider, as abrupt cessation may lead to deterioration in glycemic control or weight regain. A collaborative discussion between patient and provider can determine the most appropriate course of action, which may include further diagnostic evaluation, treatment of underlying contributing factors, symptomatic management of RLS, or consideration of alternative diabetes or weight management therapies if symptoms are severe and refractory to other interventions.

No, semaglutide is not listed among medications known to trigger RLS, and its mechanism of action does not directly involve dopaminergic pathways implicated in restless leg syndrome. However, indirect factors such as nutritional deficiencies from rapid weight loss may contribute to RLS symptoms in some patients.

Contact your healthcare provider for comprehensive evaluation including iron studies, vitamin B12, and folate levels. Do not discontinue semaglutide without medical guidance, as addressing nutritional deficiencies and implementing lifestyle modifications often resolves symptoms without stopping the medication.

Patients with type 2 diabetes have a 15-30% prevalence of RLS compared to 5-10% in the general population, primarily due to diabetic peripheral neuropathy. This elevated baseline risk means RLS symptoms during semaglutide treatment may represent natural disease progression rather than a medication effect.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.