LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

Binge eating disorder (BED) affects millions of Americans, yet treatment options remain limited. As researchers explore new therapeutic approaches, GLP-1 receptor agonists—medications originally developed for type 2 diabetes and obesity—have emerged as a potential off-label treatment. These agents work on brain reward pathways and appetite regulation systems that may be dysregulated in BED. While preliminary evidence from case reports and small studies shows promise in reducing binge frequency, no GLP-1 agonist currently holds FDA approval for this indication. Understanding the current evidence, safety considerations, and how these medications compare to established treatments is essential for patients and clinicians navigating BED management.

Quick Answer: GLP-1 agonists show preliminary promise for binge eating disorder but lack FDA approval and robust clinical trial evidence for this indication.

We offer compounded medications and Zepbound®. Compounded medications are prepared by licensed pharmacies and are not FDA-approved. References to Wegovy®, Ozempic®, Rybelsus®, Mounjaro®, or Saxenda®, or other GLP-1 brands, are informational only. Compounded and FDA-approved medications are not interchangeable.

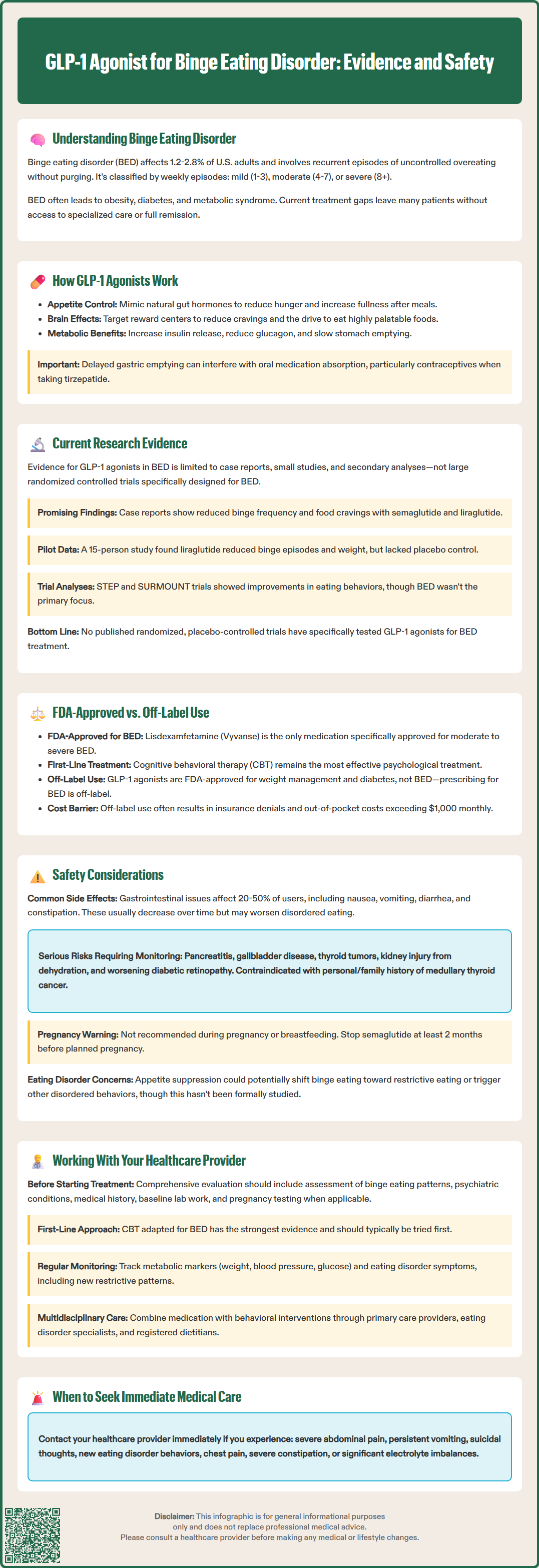

Binge eating disorder (BED) is the most common eating disorder in the United States, affecting approximately 1.2-2.8% of adults in their lifetime. It is characterized by recurrent episodes of consuming large quantities of food in a discrete period, accompanied by a sense of loss of control and marked distress. Unlike bulimia nervosa, BED does not involve compensatory behaviors such as purging or excessive exercise.

According to DSM-5-TR criteria, BED severity is classified as mild (1-3 episodes/week), moderate (4-7 episodes/week), or severe (8+ episodes/week), with each level requiring appropriate treatment intensity.

The disorder presents significant clinical challenges beyond the psychological distress it causes. Individuals with BED frequently experience comorbid conditions including obesity, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and metabolic syndrome. The relationship between BED and weight gain creates a complex cycle: binge eating episodes contribute to weight gain, while weight-related stigma and distress may trigger further binge episodes.

Current FDA-approved treatment options for BED are limited. Lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse) is the only medication specifically approved for moderate to severe BED in adults, typically used alongside psychotherapy. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) remains the gold-standard psychological intervention, with evidence supporting its efficacy in reducing binge frequency and associated psychopathology. Other medications with some evidence but not FDA approval include certain SSRIs and topiramate. However, access to specialized eating disorder treatment is often limited, and many patients do not achieve full remission with available therapies.

The neurobiological underpinnings of BED involve dysregulation in reward processing, impulse control, and appetite regulation pathways. This has led researchers to investigate medications that modulate these systems, including the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists originally developed for type 2 diabetes and obesity management. Understanding how these agents affect both metabolic and neural pathways has opened new avenues for potential BED treatment.

GLP-1 receptor agonists are a class of medications that mimic the action of glucagon-like peptide-1, an incretin hormone naturally produced in the intestinal L-cells following food intake. These agents include semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy), liraglutide (Victoza, Saxenda), dulaglutide (Trulicity), and tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Zepbound), which also targets the glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) receptor.

In the periphery, GLP-1 agonists enhance glucose-dependent insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells, suppress inappropriate glucagon release, and slow gastric emptying. These mechanisms improve glycemic control in type 2 diabetes and contribute to weight loss by prolonging satiety and reducing appetite. The delayed gastric emptying creates a sensation of fullness that persists longer after meals, though this effect may attenuate over time with continued use. This gastric slowing can also affect the absorption of some oral medications, particularly with tirzepatide, which can reduce the effectiveness of oral contraceptives.

GLP-1 receptors are distributed throughout the central nervous system, including regions involved in appetite regulation and reward processing. The hypothalamus, particularly the arcuate nucleus, contains GLP-1 receptors that modulate hunger and satiety signals. Animal studies have demonstrated that GLP-1 receptors are present in the mesolimbic reward pathway, including the ventral tegmental area and nucleus accumbens—brain regions implicated in food reward and addictive behaviors.

Research suggests that GLP-1 agonists may reduce the hedonic or reward-driven aspects of eating, not merely physiological hunger. Preclinical studies have shown that GLP-1 receptor activation decreases motivation to work for palatable food rewards and reduces consumption of highly rewarding foods. In humans, neuroimaging studies show associative evidence that GLP-1 agonists alter brain responses to food cues, potentially dampening the neural reactivity to appetizing foods that may trigger binge episodes in susceptible individuals.

The evidence base for GLP-1 agonists in binge eating disorder remains preliminary, with most data coming from case reports, small case series, and secondary analyses rather than large randomized controlled trials specifically designed for BED. However, the existing research provides intriguing signals that warrant further investigation.

Several case reports have documented reductions in binge eating frequency among patients treated with semaglutide or liraglutide for obesity or diabetes who also had BED. A 2023 case series published in the Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology reported on six patients with BED treated with semaglutide, five of whom experienced substantial reductions in binge frequency and loss of control eating. While promising, these small samples cannot establish efficacy.

Small pilot studies have begun to explore this application more systematically. One open-label study of liraglutide in 15 individuals with obesity and BED found reductions in both binge eating episodes and body weight over 17 weeks. Participants reported decreased food cravings and improved control over eating. However, the lack of a placebo control group limits interpretation, as placebo responses in eating disorder trials can be substantial.

Post-hoc analyses of weight loss trials provide additional context. In the STEP trials (semaglutide) and SURMOUNT trials (tirzepatide) for obesity, participants with baseline binge eating behaviors showed improvements in eating-related measures alongside weight loss, as assessed by questionnaires such as the Control of Eating Questionnaire. However, these trials did not specifically recruit individuals with diagnosed BED, and eating disorder symptoms were not primary outcomes.

As of this writing, there is no published randomized, placebo-controlled trial specifically examining GLP-1 agonists as a treatment for BED. The existing evidence, while promising, does not establish efficacy, optimal dosing, treatment duration, or long-term outcomes for this indication.

No GLP-1 receptor agonist currently holds FDA approval for the treatment of binge eating disorder. The only medication specifically approved for BED is lisdexamfetamine dimesylate (Vyvanse), a central nervous system stimulant approved in 2015 for moderate to severe BED in adults. Clinical trials demonstrated that lisdexamfetamine significantly reduced binge eating days per week compared to placebo, with effects maintained over six months.

Lisdexamfetamine is a Schedule II controlled substance with potential for abuse and dependence. It is contraindicated in patients taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) or with hypersensitivity to amphetamine products. The medication carries warnings and precautions regarding cardiovascular risks, blood pressure and heart rate increases, psychiatric adverse events, and potential for misuse. Patients with serious heart problems, advanced arteriosclerosis, or recent history of substance use disorder require careful evaluation and monitoring.

Several GLP-1 agonists have FDA approval for other indications that may overlap with BED patient populations:

Semaglutide (Wegovy) and liraglutide (Saxenda) are approved for chronic weight management in adults with obesity (BMI ≥30) or overweight (BMI ≥27) with at least one weight-related comorbidity

Semaglutide (Ozempic), liraglutide (Victoza), dulaglutide (Trulicity), and tirzepatide (Mounjaro) are approved for type 2 diabetes management

Tirzepatide (Zepbound) is approved for chronic weight management

When clinicians prescribe GLP-1 agonists for BED, this constitutes off-label use—a legal and common practice in medicine when evidence suggests potential benefit and approved treatments are inadequate. However, off-label prescribing carries important considerations. Insurance coverage may be limited or denied for non-approved indications, creating significant cost barriers as these medications can exceed $1,000 monthly without coverage. Additionally, the evidence base for efficacy and safety specifically in BED populations remains limited.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) remain first-line evidence-based treatments for BED, with robust data supporting their efficacy. The American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines recommend psychotherapy as initial treatment, with medication considered when psychotherapy is unavailable, declined, or insufficient.

GLP-1 receptor agonists are generally well-tolerated, but clinicians and patients must understand their adverse effect profile, particularly when considering use in individuals with eating disorders who may have unique vulnerabilities.

Common gastrointestinal side effects occur in the majority of patients and include nausea (reported in 20-50% depending on the agent and dose), vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, and abdominal pain. These effects are typically dose-dependent and often diminish over time with continued use. However, in individuals with BED, severe nausea or vomiting could potentially trigger or exacerbate disordered eating patterns or lead to nutritional deficiencies if food intake becomes severely restricted.

Serious adverse effects require careful monitoring:

Pancreatitis: GLP-1 agonists carry warnings about acute pancreatitis risk. These medications should generally be avoided in patients with a history of pancreatitis. Patients should be counseled to report severe abdominal pain immediately

Gallbladder disease: Increased risk of cholelithiasis and cholecystitis, likely related to rapid weight loss

Hypoglycemia: Risk is low when used alone but increases when combined with insulin or sulfonylureas

Thyroid C-cell tumors: Based on rodent studies, these agents carry a boxed warning and are contraindicated in patients with personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma or Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia syndrome type 2

Acute kidney injury: Can occur, particularly with dehydration from gastrointestinal side effects

Diabetic retinopathy complications: Semaglutide may worsen diabetic retinopathy in patients with diabetes, particularly with rapid improvement in glucose control

Severe gastrointestinal disease: Use with caution in patients with gastroparesis or severe gastrointestinal disease; rare cases of intestinal obstruction have been reported

Pregnancy and lactation: GLP-1 agonists are not recommended during pregnancy or breastfeeding. Women of childbearing potential should use effective contraception during treatment. For semaglutide, discontinuation at least 2 months before a planned pregnancy is recommended due to its long half-life. With tirzepatide, non-oral contraceptive methods should be considered for 4 weeks after initiation and dose increases due to reduced oral contraceptive efficacy.

Specific concerns in eating disorder populations warrant consideration. Rapid weight loss may not be appropriate for all individuals with BED, particularly those without obesity. There is theoretical concern that appetite suppression could transition binge eating patterns toward restrictive eating or trigger other eating disorder behaviors, though this has not been systematically studied. Additionally, the psychological aspects of BED—including emotional regulation difficulties and the functional role of binge eating—may not be adequately addressed by medication alone.

Patients should be monitored for signs of dehydration, electrolyte abnormalities, and nutritional deficiencies, particularly if gastrointestinal side effects limit intake. Mental health symptoms, including depression and suicidal ideation, should be assessed regularly, as these may occur in the context of eating disorders regardless of treatment.

Individuals considering GLP-1 agonists for binge eating disorder should engage in thorough, collaborative discussions with healthcare providers who understand both the medications and eating disorders. A comprehensive treatment approach typically involves multiple specialists.

Initial evaluation should include a detailed assessment of binge eating patterns, frequency, triggers, and associated distress. Providers should screen for other eating disorder symptoms, psychiatric comorbidities (particularly depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders), and medical complications of BED. A complete medical history, including cardiovascular risk factors, thyroid disease, pancreatitis history, and current medications, is essential before considering GLP-1 agonist therapy.

Baseline testing typically includes comprehensive metabolic panel, hemoglobin A1C or fasting glucose, lipid panel, and pregnancy testing when applicable. For patients with diabetes, retinal examination should be considered before starting semaglutide.

Treatment planning should prioritize evidence-based interventions. Patients should be informed that psychotherapy, particularly CBT adapted for BED, has the strongest evidence base and should typically be considered first-line treatment. When medication is appropriate, the discussion should include:

The limited evidence for GLP-1 agonists specifically in BED

FDA-approved alternatives, including lisdexamfetamine

Realistic expectations about outcomes and timeline

Potential side effects and monitoring requirements

Cost considerations and insurance coverage

The importance of combining medication with behavioral interventions

Monitoring during treatment should be systematic and multifaceted. Beyond standard metabolic monitoring (weight, blood pressure, glucose, lipids), providers should regularly assess binge eating frequency, eating disorder cognitions, mood symptoms, and quality of life. Patients should be asked specifically about any new restrictive eating patterns, compensatory behaviors, or shifts in eating disorder symptoms.

Red flags requiring immediate evaluation include severe abdominal pain (possible pancreatitis), persistent vomiting leading to dehydration, suicidal thoughts, development of new eating disorder behaviors, syncope, chest pain, hematemesis/melena, severe constipation/obstipation, orthostatic hypotension, or marked electrolyte abnormalities. Patients should have clear instructions on when to seek emergency care and how to contact their provider.

Given the complexity of eating disorders, multidisciplinary care is ideal, involving collaboration between primary care providers, psychiatrists or psychologists specializing in eating disorders, and registered dietitians. This team approach addresses the biological, psychological, and nutritional aspects of BED comprehensively. Patients should be empowered as active participants in treatment decisions, with ongoing dialogue about benefits, risks, and treatment goals tailored to their individual circumstances.

No GLP-1 receptor agonist currently has FDA approval for treating binge eating disorder. Lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse) is the only medication specifically approved for moderate to severe BED in adults, while GLP-1 agonists may be prescribed off-label based on emerging evidence.

GLP-1 agonists work on brain reward pathways and appetite regulation centers, potentially reducing the hedonic or reward-driven aspects of eating. They slow gastric emptying, prolong satiety, and may dampen neural reactivity to food cues that trigger binge episodes.

Common side effects include nausea, vomiting, and gastrointestinal symptoms. Serious risks include pancreatitis, gallbladder disease, and potential for triggering restrictive eating patterns in individuals with eating disorders. These medications require careful monitoring by healthcare providers experienced in eating disorder treatment.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.