LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

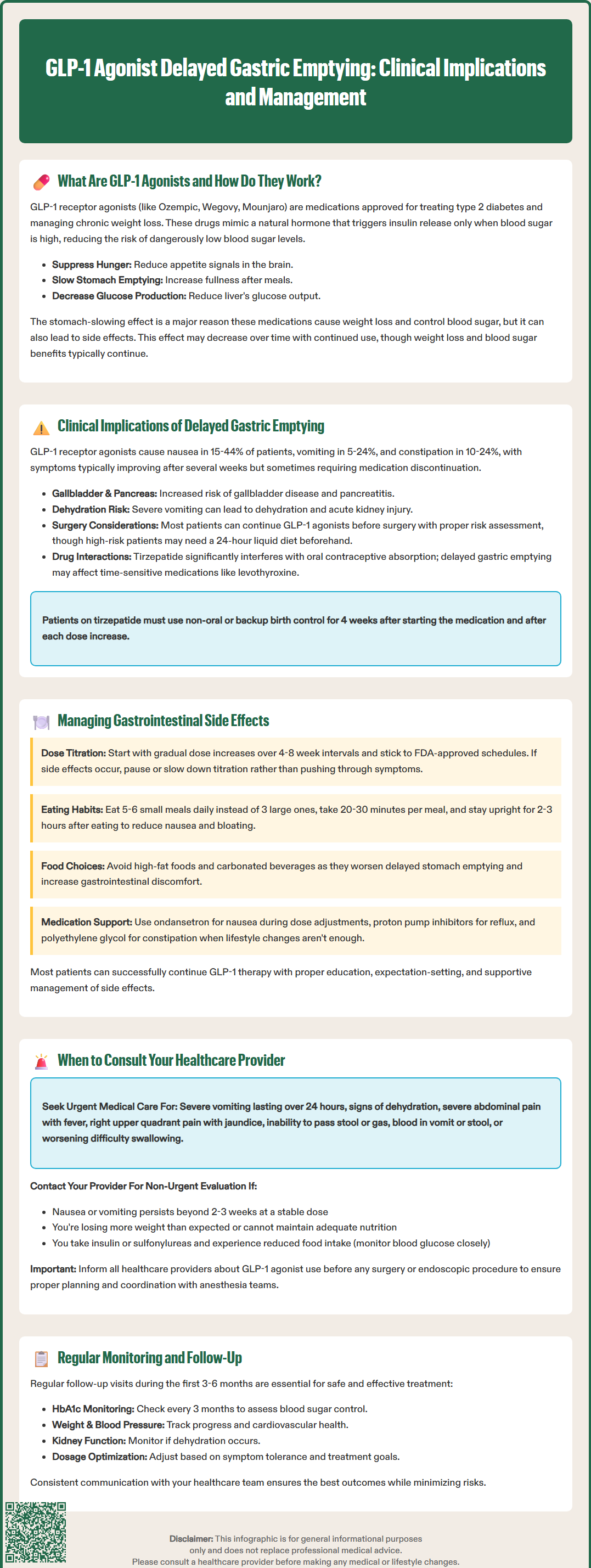

GLP-1 receptor agonists have transformed the management of type 2 diabetes and obesity, but their mechanism of delaying gastric emptying presents important clinical considerations. While this effect contributes to weight loss and glycemic control by prolonging satiety and moderating glucose excursions, it can also produce gastrointestinal symptoms and affect perioperative care. Understanding how GLP-1 agonist delayed gastric emptying impacts patient safety, medication tolerance, and procedural planning is essential for clinicians prescribing these increasingly common medications. This article examines the mechanisms, clinical implications, management strategies, and situations requiring medical consultation related to GLP-1-induced delayed gastric emptying.

Quick Answer: GLP-1 receptor agonists delay gastric emptying as a therapeutic mechanism that contributes to weight loss and glycemic control but can cause gastrointestinal symptoms and perioperative complications.

We offer compounded medications and Zepbound®. Compounded medications are prepared by licensed pharmacies and are not FDA-approved. References to Wegovy®, Ozempic®, Rybelsus®, Mounjaro®, or Saxenda®, or other GLP-1 brands, are informational only. Compounded and FDA-approved medications are not interchangeable.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists represent a class of medications primarily used for managing type 2 diabetes mellitus and, more recently, for chronic weight management. These agents include semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy, Rybelsus), dulaglutide (Trulicity), and liraglutide (Victoza, Saxenda), among others. Tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Zepbound) works through a distinct dual mechanism as a GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist. The FDA has approved various formulations for different indications, with growing clinical use across multiple patient populations.

The mechanism of action centers on mimicking endogenous GLP-1, an incretin hormone naturally released from intestinal L-cells following food intake. GLP-1 receptor agonists bind to GLP-1 receptors located throughout the body, including the pancreas, gastrointestinal tract, and central nervous system. This binding triggers multiple physiological responses that contribute to glycemic control and weight reduction.

Key pharmacological effects include:

Glucose-dependent insulin secretion – Enhanced pancreatic beta-cell insulin release only when blood glucose is elevated, reducing hypoglycemia risk

Suppression of glucagon secretion – Decreased hepatic glucose production from pancreatic alpha cells

Delayed gastric emptying – Slowed movement of food from the stomach to the small intestine

Central appetite regulation – Reduced hunger and increased satiety through hypothalamic pathways

The delayed gastric emptying effect is particularly significant and represents both a therapeutic mechanism and a potential source of adverse effects. By slowing the rate at which the stomach empties its contents into the duodenum, GLP-1 agonists prolong the sensation of fullness, contribute to reduced caloric intake, and moderate postprandial glucose excursions. Importantly, this effect often attenuates over time with long-acting agents (tachyphylaxis), though the weight loss and glycemic benefits typically persist. The delayed gastric emptying effect varies in intensity among different agents and individual patients, with clinical implications that warrant careful consideration in practice.

Delayed gastric emptying induced by GLP-1 receptor agonists carries important clinical implications that extend beyond the intended therapeutic effects. While this mechanism contributes to weight loss and glycemic control, it can produce gastrointestinal symptoms and affect other aspects of patient care.

Gastrointestinal symptom profile:

The most commonly reported adverse effects directly relate to delayed gastric motility. According to FDA prescribing information, nausea occurs in 15-44% of patients depending on the specific agent and dose, with vomiting affecting 5-24% and constipation occurring in 10-24% of users. These symptoms typically emerge during dose escalation and often diminish over several weeks as physiological adaptation occurs. However, some patients experience persistent symptoms that may limit medication tolerance or necessitate discontinuation.

Abdominal distension, early satiety, and gastroesophageal reflux symptoms may also develop as consequences of prolonged gastric retention. Severe vomiting can lead to dehydration and acute kidney injury in some cases. Additionally, GLP-1 receptor agonists carry risks of gallbladder disease (cholelithiasis, cholecystitis) and pancreatitis that may present with abdominal pain and other gastrointestinal symptoms.

Perioperative considerations:

Delayed gastric emptying has emerged as a significant concern in the perioperative setting. The American Society of Anesthesiologists and other professional organizations issued 2024 multi-society guidance regarding GLP-1 agonist use before procedures requiring anesthesia. Current recommendations suggest most patients can continue therapy with appropriate risk stratification rather than routine holds. High-risk patients may benefit from a 24-hour liquid diet before procedures, and coordination with anesthesia providers is essential. Preoperative assessment should include specific inquiry about GLP-1 agonist use, and consideration of gastric ultrasound may be appropriate in certain cases.

Drug absorption and interactions:

Delayed gastric emptying can theoretically affect the absorption kinetics of orally administered medications, particularly those with narrow therapeutic windows or requiring rapid onset. A clinically significant interaction exists between tirzepatide and oral contraceptives, with FDA labeling advising use of non-oral or backup contraception for 4 weeks after initiation and each dose increase. Patients taking levothyroxine or other time-sensitive medications warrant closer monitoring during GLP-1 agonist initiation.

Effective management of GLP-1 agonist-related gastrointestinal effects requires a systematic approach combining patient education, lifestyle modifications, and appropriate clinical interventions. Most patients can successfully continue therapy with proper support and expectation-setting.

Dose titration strategies:

Gradual dose escalation represents the cornerstone of minimizing gastrointestinal adverse effects. FDA-approved titration schedules typically involve 4-8 week intervals between dose increases, allowing physiological adaptation to occur. Clinicians should adhere to these schedules rather than accelerating titration, even when patients are tolerating current doses well. For patients experiencing significant symptoms, temporarily pausing therapy, maintaining the current dose for an additional 2-4 weeks before advancing, or implementing smaller dose increments when formulation allows, may improve tolerance.

Dietary and lifestyle modifications:

Patients benefit from specific guidance regarding eating patterns and food choices:

Smaller, more frequent meals – Consuming 5-6 small meals rather than 3 large meals reduces gastric distension

Slower eating pace – Taking 20-30 minutes per meal and chewing thoroughly

Avoiding high-fat foods – Fatty meals delay gastric emptying further and may exacerbate symptoms

Limiting very high-fiber foods – During symptomatic periods, as these can worsen bloating

Limiting carbonated beverages – Reducing bloating and distension

Adequate hydration – Maintaining fluid intake between meals rather than with meals

Remaining upright after eating – Avoiding recumbent positions for 2-3 hours post-meal

Symptomatic management:

When lifestyle modifications prove insufficient, pharmacological interventions may provide relief. For nausea, ondansetron or other antiemetics can be used short-term during dose escalation periods. Proton pump inhibitors may benefit patients with reflux symptoms, though they do not address the underlying motility issue. Osmotic laxatives like polyethylene glycol can manage constipation effectively.

Prokinetic agents like metoclopramide present a theoretical option but should be used cautiously given potential adverse effects (including tardive dyskinesia with use beyond 12 weeks) and the counterintuitive nature of accelerating gastric emptying while using a medication that intentionally slows it. There is limited evidence supporting this approach, and it should be reserved for severe, refractory cases under gastroenterology specialist guidance.

While mild gastrointestinal symptoms are expected with GLP-1 agonist therapy, certain presentations warrant prompt medical evaluation. Patients and clinicians should maintain clear communication regarding symptom severity and trajectory.

Red flag symptoms requiring urgent assessment:

Severe, persistent vomiting – Inability to tolerate oral intake for more than 24 hours, suggesting possible gastroparesis or other complications

Signs of dehydration – Decreased urine output, dizziness, dry mucous membranes, or tachycardia

Severe abdominal pain – Particularly if acute, localized, or associated with fever, which may indicate pancreatitis or other acute abdominal pathology

Right upper quadrant pain, fever, or jaundice – Suggesting possible gallbladder disease

Severe abdominal distension with inability to pass stool or gas – Potential bowel obstruction or ileus

Hematemesis or melena – Suggesting gastrointestinal bleeding

Progressive dysphagia – Difficulty swallowing that worsens over time

Situations requiring routine consultation:

Patients should contact their healthcare provider for non-urgent evaluation when experiencing persistent nausea or vomiting lasting beyond 2-3 weeks at a stable dose, as this may indicate inadequate adaptation or the need for dose adjustment. Unintentional weight loss exceeding expected therapeutic goals, or inability to maintain adequate nutritional intake, requires assessment for excessive medication effect or other underlying conditions.

Patients taking insulin or sulfonylureas should monitor blood glucose closely during periods of reduced intake and contact their provider for medication adjustments to prevent hypoglycemia.

Before scheduled surgical or endoscopic procedures, patients must inform all healthcare providers about GLP-1 agonist use. Risk stratification and individualized plans should be developed in coordination with anesthesia providers.

Monitoring and follow-up:

Regular follow-up during the first 3-6 months of therapy allows for symptom assessment, dose optimization, and early identification of complications. The American Diabetes Association recommends monitoring HbA1c every 3 months during dose titration, with assessment of weight, blood pressure, and medication tolerance at each visit. Renal function should be checked if dehydration is suspected.

Patients with persistent symptoms despite appropriate management may benefit from gastroenterology consultation. Diagnostic testing such as gastric emptying scintigraphy should be performed after appropriate washout of GLP-1 receptor agonists per American College of Gastroenterology guidelines.

Patients with pre-existing gastroparesis, significant gastrointestinal disease, or previous gastric surgery require particularly careful monitoring and may benefit from gastroenterology consultation before initiating GLP-1 agonist therapy. Shared decision-making should incorporate discussion of the delayed gastric emptying effect and its potential implications for each individual's clinical circumstances.

The delayed gastric emptying effect often attenuates over time with long-acting GLP-1 agonists through tachyphylaxis, though the weight loss and glycemic benefits typically persist. Most gastrointestinal symptoms diminish over several weeks as physiological adaptation occurs, particularly after the initial dose escalation period.

Current 2024 multi-society guidance suggests most patients can continue GLP-1 agonist therapy with appropriate risk stratification rather than routine holds. You should inform all healthcare providers about your medication use, and your anesthesia team will develop an individualized plan based on your specific procedure and risk factors.

Delayed gastric emptying can theoretically affect absorption of oral medications, particularly those with narrow therapeutic windows. A clinically significant interaction exists between tirzepatide and oral contraceptives, requiring backup contraception for 4 weeks after initiation and each dose increase, and patients taking levothyroxine or other time-sensitive medications warrant closer monitoring.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.