LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

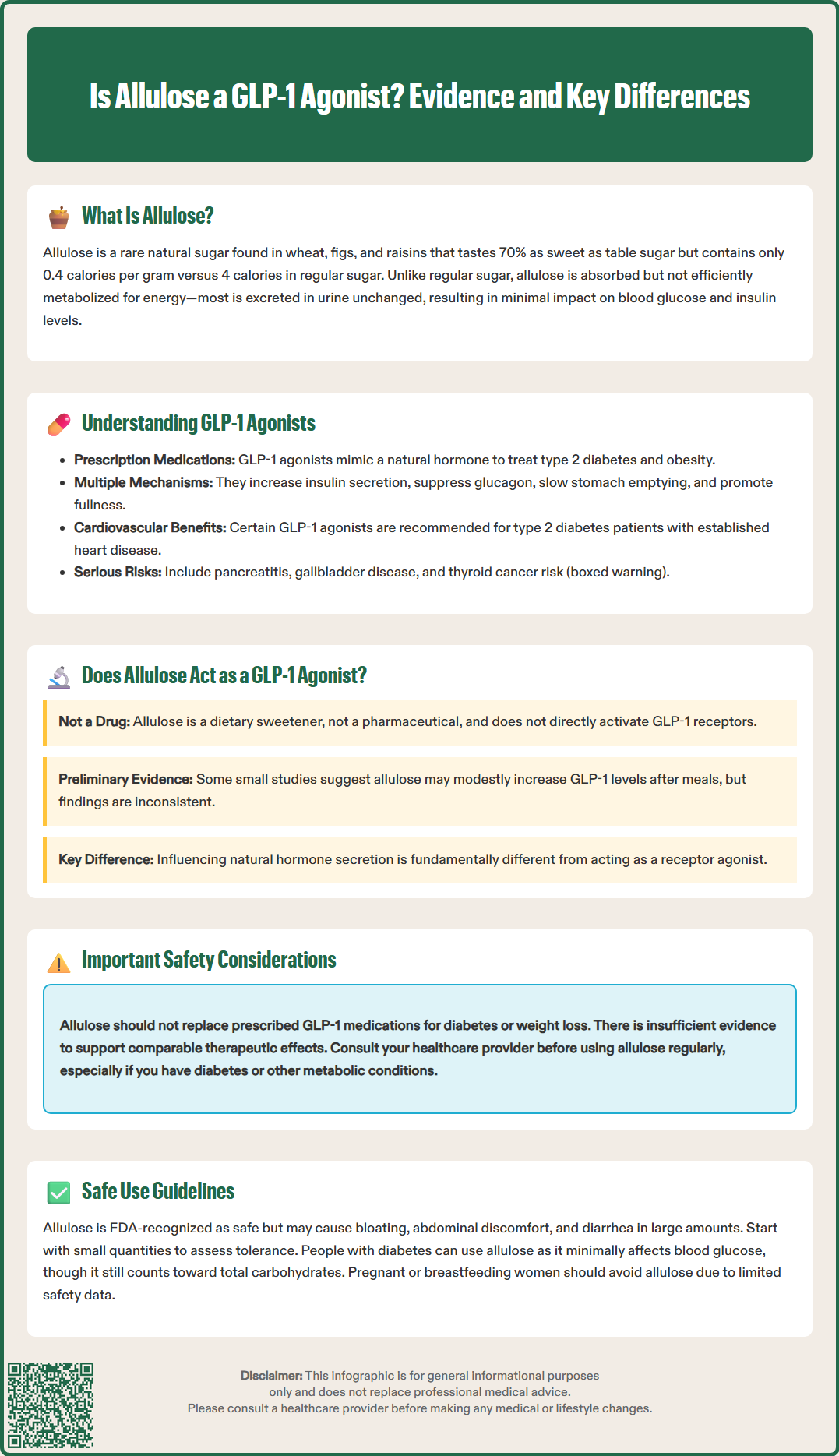

Is allulose a GLP-1 agonist? This question has emerged as consumers seek natural alternatives to prescription medications for blood sugar management. Allulose is a low-calorie rare sugar with FDA GRAS status, found naturally in small amounts in wheat, figs, and raisins. While it has minimal impact on blood glucose, allulose is fundamentally different from GLP-1 agonist medications like semaglutide or liraglutide. Understanding the distinction between this dietary sweetener and prescription incretin mimetics is essential for patients with diabetes and healthcare providers making evidence-based treatment decisions.

Quick Answer: Allulose is not a GLP-1 agonist and does not function as a pharmaceutical GLP-1 receptor agonist medication.

We offer compounded medications and Zepbound®. Compounded medications are prepared by licensed pharmacies and are not FDA-approved. References to Wegovy®, Ozempic®, Rybelsus®, Mounjaro®, or Saxenda®, or other GLP-1 brands, are informational only. Compounded and FDA-approved medications are not interchangeable.

Allulose, also known as D-psicose, is a rare sugar that occurs naturally in small quantities in foods such as wheat, figs, and raisins. Chemically classified as an epimer of fructose, allulose has approximately 70% of the sweetness of table sugar but provides only about 0.4 calories per gram compared to sucrose's 4 calories per gram. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has recognized allulose as Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS). In 2019, the FDA issued guidance excluding allulose from total and added sugar counts on nutrition labels, though it is still included in total carbohydrates.

When consumed, allulose is absorbed in the small intestine but is not efficiently metabolized for energy. Research suggests that a significant portion is excreted unchanged in the urine, with some undergoing colonic fermentation. This limited metabolism explains its minimal impact on blood glucose and insulin levels. Unlike artificial sweeteners, allulose is a naturally occurring monosaccharide that the body recognizes but processes differently than conventional sugars.

The mechanism by which allulose exerts its effects differs fundamentally from pharmaceutical agents. It does not bind to specific receptors or trigger direct hormonal responses in the manner of medications. Some preliminary research, primarily from animal studies with limited human data, suggests allulose may influence glucose metabolism and potentially improve insulin sensitivity, though these mechanisms remain under investigation and require further validation in robust human clinical trials.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists, also called GLP-1 receptor agonists or incretin mimetics, are a class of prescription medications used primarily to manage type 2 diabetes mellitus and, in some formulations, obesity. These pharmaceutical agents work by mimicking the action of endogenous GLP-1, an incretin hormone secreted by intestinal L-cells in response to food intake. FDA-approved GLP-1 agonists include semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy, Rybelsus), dulaglutide (Trulicity), liraglutide (Victoza, Saxenda), and exenatide (Byetta, Bydureon), among others. While most require subcutaneous injection, oral semaglutide (Rybelsus) is available as a tablet.

The mechanism of action of GLP-1 agonists involves binding to GLP-1 receptors on pancreatic beta cells, which stimulates glucose-dependent insulin secretion. This means insulin release occurs primarily when blood glucose levels are elevated, reducing the risk of hypoglycemia compared to some other diabetes medications. Additionally, GLP-1 agonists suppress glucagon secretion from pancreatic alpha cells, slow gastric emptying, and promote satiety through central nervous system effects, contributing to weight loss in many patients.

Clinically, certain GLP-1 agonists have demonstrated cardiovascular benefits. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) guidelines recommend specific GLP-1 agonists with proven cardiovascular benefit (such as liraglutide, injectable semaglutide, and dulaglutide) for patients with type 2 diabetes and established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. For patients with heart failure or chronic kidney disease, SGLT2 inhibitors are generally preferred, with GLP-1 agonists considered when SGLT2 inhibitors are not appropriate or for additional benefit. Common adverse effects include gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, which typically diminish over time. More serious risks include pancreatitis (requiring immediate medical attention if severe abdominal pain occurs), gallbladder disease, and a boxed warning for medullary thyroid carcinoma risk (contraindicated in patients with personal/family history of MTC or Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia syndrome type 2). GLP-1 agonists are not indicated for type 1 diabetes.

There is no established evidence that allulose functions as a GLP-1 agonist in the pharmacological sense. Allulose is a dietary sweetener with GRAS status as a food ingredient, not a pharmaceutical compound, and it does not directly bind to or activate GLP-1 receptors as prescription GLP-1 agonist medications do. The mechanisms of action are fundamentally different: GLP-1 agonists are synthetic or modified peptides designed to mimic incretin hormones and directly stimulate specific cellular receptors, while allulose is a simple sugar that undergoes passive absorption and excretion.

Some preliminary animal studies and limited human research have explored whether allulose consumption might indirectly influence incretin hormone secretion, including GLP-1. A few small studies have suggested that allulose may modestly increase postprandial GLP-1 levels when consumed with carbohydrates, potentially through mechanisms involving intestinal sensing of nutrients. However, these findings are preliminary, inconsistent across studies, and do not demonstrate that allulose acts as a GLP-1 agonist. Any observed increases in GLP-1 secretion would represent an indirect effect of nutrient sensing rather than direct receptor activation.

It is critical to distinguish between a substance that may influence endogenous hormone secretion and one that functions as a receptor agonist. The clinical significance of any potential GLP-1 modulation by allulose remains uncertain and has not been validated in rigorous human trials. Patients should not consider allulose a substitute for prescribed GLP-1 agonist medications or expect comparable therapeutic effects for diabetes management or weight loss. The evidence base for allulose's metabolic effects is insufficient to support claims of GLP-1 agonist activity, and such characterizations would be scientifically inaccurate and potentially misleading.

Allulose is generally well tolerated when consumed in moderate amounts, with the FDA recognizing it as safe for use as a food ingredient. The most commonly reported adverse effects are gastrointestinal in nature, including bloating, abdominal discomfort, and diarrhea, particularly when consumed in larger quantities. Individual tolerance varies, and gradual introduction is advisable to assess personal response. If severe or persistent gastrointestinal symptoms occur, especially with signs of dehydration, discontinue use and consult a healthcare provider.

For individuals with diabetes, allulose appears to have minimal impact on blood glucose levels and does not require insulin dose adjustments in the way that regular sugars do. However, patients should be aware that allulose is still counted in total carbohydrates on nutrition labels, which may be relevant for carbohydrate counting. Patients taking diabetes medications should monitor their blood glucose as they would with any dietary change. There is insufficient evidence to recommend allulose as a therapeutic intervention for glycemic control, and it should not replace prescribed medications or established dietary management strategies.

Pregnant or breastfeeding individuals should exercise caution with allulose, as safety data in these populations are limited. Similarly, individuals with pre-existing gastrointestinal conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome may experience exacerbated symptoms with allulose consumption due to its osmotic effects. While allulose does not appear to interact with medications in the manner of pharmaceutical agents, patients should inform their healthcare providers about all dietary supplements and food ingredients they consume regularly. As with any dietary modification, consultation with a healthcare provider or registered dietitian is recommended, particularly for those with diabetes or other metabolic conditions.

No, allulose cannot replace prescription GLP-1 agonist medications. Allulose is a dietary sweetener with minimal metabolic effects, while GLP-1 agonists are FDA-approved prescription drugs with proven efficacy for type 2 diabetes management and cardiovascular benefits.

Some preliminary studies suggest allulose may modestly increase postprandial GLP-1 secretion indirectly through nutrient sensing mechanisms. However, this evidence is limited, inconsistent, and does not demonstrate clinically significant effects comparable to prescription GLP-1 agonists.

Allulose is generally safe for individuals with diabetes and has minimal impact on blood glucose levels. However, it should not replace prescribed medications or established dietary management, and patients should consult their healthcare provider before incorporating it into their diabetes care plan.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.