LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

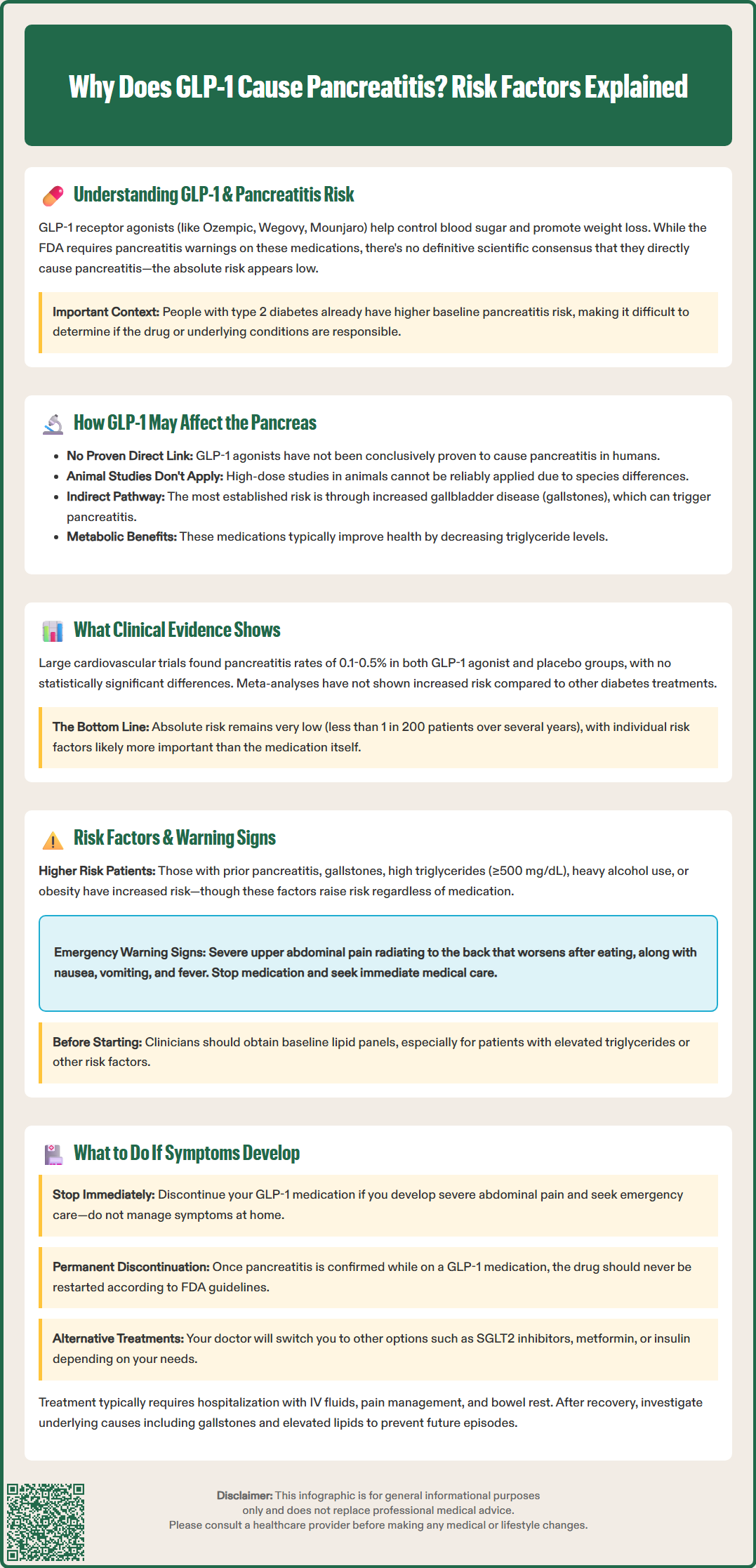

Concerns about pancreatitis have emerged since GLP-1 receptor agonists like semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy) and liraglutide (Victoza) became widely prescribed for type 2 diabetes and weight management. While the FDA requires pancreatitis warnings on these medications, the exact causal relationship remains unclear. Patients with diabetes already face elevated pancreatitis risk due to obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, and metabolic syndrome—conditions common among those prescribed GLP-1 medications. This overlap makes determining whether observed cases represent a true drug effect or reflect underlying patient susceptibility challenging. Understanding this nuanced relationship helps clinicians make informed prescribing decisions and enables patients to recognize warning signs requiring immediate medical attention.

Quick Answer: The exact mechanism by which GLP-1 receptor agonists might cause pancreatitis remains unproven, though proposed pathways include indirect effects through increased gallbladder disease risk rather than direct pancreatic toxicity.

We offer compounded medications and Zepbound®. Compounded medications are prepared by licensed pharmacies and are not FDA-approved. References to Wegovy®, Ozempic®, Rybelsus®, Mounjaro®, or Saxenda®, or other GLP-1 brands, are informational only. Compounded and FDA-approved medications are not interchangeable.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists have become widely prescribed medications for type 2 diabetes and weight management in the United States. This class includes semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy), dulaglutide (Trulicity), and liraglutide (Victoza, Saxenda). Tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Zepbound) is a related but distinct medication that acts as a dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and GLP-1 receptor agonist. These medications work by mimicking natural hormones that regulate blood sugar and appetite, leading to improved glycemic control and significant weight loss in many patients.

Since their introduction, concerns have emerged regarding a potential association between these medications and acute pancreatitis—a serious inflammatory condition of the pancreas. The FDA has required manufacturers to include pancreatitis warnings in prescribing information for all GLP-1 medications, though the exact causal relationship remains incompletely understood. It is important to note that there is no definitive scientific consensus that these drugs directly cause pancreatitis, and the absolute risk appears to be low based on clinical trial data.

Patients with type 2 diabetes already face an elevated baseline risk of pancreatitis compared to the general population, independent of medication use. Obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, and metabolic syndrome—conditions commonly present in patients prescribed GLP-1 agonists—are themselves established risk factors for pancreatic inflammation. This overlap makes it challenging to determine whether observed cases represent a true drug effect or reflect the underlying patient population's inherent susceptibility.

Understanding the nuanced relationship between GLP-1 medications and pancreatitis helps clinicians make informed prescribing decisions and enables patients to recognize warning signs that warrant immediate medical attention.

The proposed mechanisms by which GLP-1 receptor agonists might influence pancreatic health involve several biological pathways, though none have been conclusively proven to cause pancreatitis in humans. While GLP-1 receptors are primarily found on pancreatic beta cells, their presence and significance on human pancreatic acinar and ductal cells remains uncertain, with earlier research complicated by antibody specificity issues.

Animal studies, particularly in rodents, have shown that high-dose GLP-1 exposure can lead to pancreatic ductal proliferation and, in some cases, inflammatory changes. However, extrapolating these findings to human physiology is problematic due to significant species differences in pancreatic anatomy, GLP-1 receptor distribution, and metabolic responses. The doses used in animal research often far exceed those used therapeutically in humans when adjusted for body surface area.

A more established pathway may involve gallbladder and biliary effects. Clinical studies and meta-analyses have identified an increased risk of gallbladder disease with GLP-1 receptor agonist use, particularly with weight loss medications. Gallstones and biliary sludge are known triggers for acute pancreatitis, potentially creating an indirect pathway between these medications and pancreatic inflammation in some patients.

GLP-1 receptor agonists slow gastric emptying, which has been hypothesized to affect pancreatic function, though this connection remains speculative and lacks supporting clinical evidence. Contrary to some hypotheses, these medications typically improve lipid profiles rather than worsen them, with most patients experiencing decreases in triglyceride levels during treatment.

It is crucial to emphasize that these mechanisms represent hypotheses rather than established pathophysiology. Large-scale human studies have not identified a clear dose-response relationship or consistent temporal pattern that would support a direct causal link. The pancreatic effects of GLP-1 receptor activation in humans appear to be complex and likely influenced by individual patient factors, pre-existing pancreatic health, and concurrent metabolic conditions.

The clinical evidence regarding GLP-1 receptor agonists and pancreatitis presents a complex picture. Post-marketing surveillance and case reports have documented instances of acute pancreatitis in patients taking these medications, prompting regulatory agencies to investigate the association. However, establishing causality in pharmacovigilance is inherently challenging, as temporal association does not prove causation.

Large cardiovascular outcome trials have provided the most robust safety data available. The LEADER trial (liraglutide) reported pancreatitis in 0.3% of liraglutide patients versus 0.1% of placebo patients over a median 3.8 years. SUSTAIN-6 (semaglutide) showed acute pancreatitis in 0.3% of semaglutide patients versus 0.2% of placebo patients. The REWIND trial (dulaglutide) found acute pancreatitis in 0.5% of dulaglutide patients versus 0.4% of placebo patients. None of these differences reached statistical significance, though the studies were not powered specifically for this outcome.

Comprehensive meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials have generally not found statistically significant increases in pancreatitis risk with GLP-1 agonists compared to other diabetes treatments. However, real-world observational studies have yielded mixed results. Some large database analyses have suggested a modest increase in pancreatitis risk, particularly in the first few months after initiation, while others have found no association after adjusting for confounding factors such as obesity, gallbladder disease, and alcohol use.

The American Diabetes Association's Standards of Care acknowledge the ongoing uncertainty, noting that while pancreatitis has been reported with GLP-1 receptor agonist use, a definitive causal relationship has not been established. The absolute incidence of pancreatitis in clinical trials has been consistently low across studies, typically affecting fewer than 1 in 200 patients over multi-year follow-up periods. Individual patient risk factors likely play a more significant role than the medication itself in determining pancreatitis susceptibility.

Certain patient characteristics may increase the likelihood of developing pancreatitis while taking GLP-1 receptor agonists, though these same factors elevate risk regardless of medication use. Established risk factors include:

History of pancreatitis: Patients with prior episodes face substantially higher recurrence risk and require careful consideration before initiating GLP-1 therapy

Gallstone disease: Cholelithiasis and biliary sludge can precipitate pancreatitis, particularly during periods of rapid weight loss

Hypertriglyceridemia: Triglyceride levels ≥1,000 mg/dL significantly increase pancreatitis risk, with risk beginning to rise at levels ≥500 mg/dL

Excessive alcohol consumption: Alcohol remains one of the most common pancreatitis triggers and may interact with metabolic changes induced by GLP-1 medications

Obesity and rapid weight loss: While weight reduction is therapeutic, very rapid loss may increase gallstone formation

Warning signs of acute pancreatitis that patients should recognize include severe, persistent abdominal pain, typically in the upper abdomen and often radiating to the back. The pain characteristically worsens after eating and is not relieved by over-the-counter medications. Associated symptoms frequently include nausea, vomiting, fever, and abdominal tenderness.

Patients experiencing these symptoms should discontinue their GLP-1 medication immediately and seek urgent medical evaluation. Diagnosis of acute pancreatitis typically requires at least two of the following three criteria (Atlanta classification): characteristic abdominal pain, serum lipase or amylase elevated to at least three times the upper limit of normal, and imaging findings consistent with pancreatic inflammation.

Clinicians should consider obtaining baseline lipid panels before initiating GLP-1 therapy, particularly in patients with known hypertriglyceridemia or other risk factors for pancreatitis. Patient education about warning signs at the time of prescribing enables early recognition and appropriate response, potentially preventing progression to severe or necrotizing pancreatitis.

If you develop symptoms suggestive of pancreatitis while taking a GLP-1 medication, immediate action is essential. Stop taking your GLP-1 medication as soon as severe abdominal pain develops—do not wait for a scheduled appointment or attempt to manage symptoms at home with over-the-counter remedies. Contact your healthcare provider immediately or, if symptoms are severe, go directly to an emergency department for evaluation.

In the emergency setting, clinicians will perform blood tests to measure pancreatic enzymes (lipase and amylase) and assess for complications. Imaging studies help confirm the diagnosis and determine severity. Acute pancreatitis requires supportive care, which may include hospitalization, intravenous fluids, pain management, and bowel rest. Most cases resolve with conservative management, though severe pancreatitis can lead to serious complications requiring intensive care.

Once acute pancreatitis has been confirmed in a patient taking a GLP-1 receptor agonist, the medication should not be restarted. According to FDA prescribing information, these medications should be discontinued promptly if pancreatitis is suspected and should not be restarted if pancreatitis is confirmed. For patients with a history of pancreatitis, FDA labeling advises considering other antidiabetic or weight management therapies, though this is not a formal contraindication.

Your healthcare provider will need to identify alternative treatment strategies for diabetes management or weight loss. Options may include SGLT2 inhibitors, metformin, thiazolidinediones, or insulin for diabetes, noting that DPP-4 inhibitors also carry pancreatitis warnings. The appropriate alternative depends on your individual clinical situation and treatment goals.

After recovery from pancreatitis, investigation into underlying causes is important. Your physician may recommend abdominal ultrasound to evaluate for gallstones, lipid panel assessment, and review of alcohol intake and other medications. Addressing modifiable risk factors reduces the likelihood of recurrent episodes regardless of the initial trigger.

For patients without a history of pancreatitis who are considering GLP-1 therapy, discussing your individual risk profile with your healthcare provider before starting treatment allows for informed decision-making. The benefits of improved glycemic control and weight loss must be weighed against potential risks in the context of your complete medical history and risk factor profile.

Patients with a history of pancreatitis face substantially higher recurrence risk and should discuss alternative treatments with their healthcare provider, as FDA labeling advises considering other therapies in this population.

Severe, persistent upper abdominal pain radiating to the back, worsening after eating, accompanied by nausea, vomiting, and fever are key warning signs requiring immediate medication discontinuation and emergency evaluation.

Clinical trials show pancreatitis affects fewer than 1 in 200 patients over multi-year follow-up, with most large studies finding no statistically significant increase compared to placebo after adjusting for underlying risk factors.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.