LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

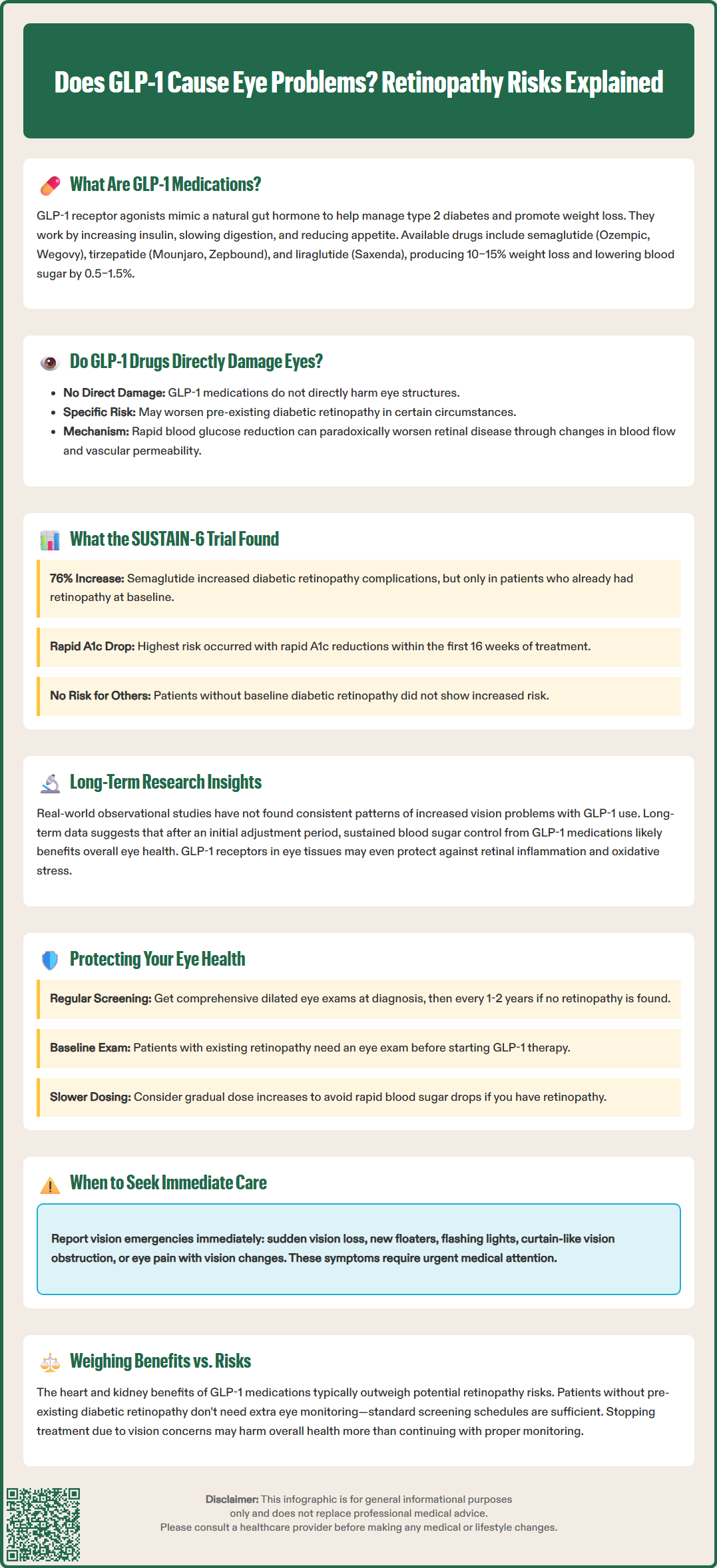

Does GLP-1 cause eye problems? This question has gained attention as GLP-1 receptor agonists like semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy) and tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Zepbound) become increasingly prescribed for type 2 diabetes and weight management. While these medications don't directly damage eye structures, clinical evidence shows they may worsen diabetic retinopathy in specific circumstances—particularly when patients with pre-existing retinal disease experience rapid blood sugar improvements. Understanding this nuanced relationship helps patients and clinicians make informed decisions about GLP-1 therapy while protecting vision through appropriate monitoring and individualized treatment approaches.

Quick Answer: GLP-1 receptor agonists do not directly cause eye damage but may worsen diabetic retinopathy in patients with pre-existing retinal disease who experience rapid blood glucose reductions.

We offer compounded medications and Zepbound®. Compounded medications are prepared by licensed pharmacies and are not FDA-approved. References to Wegovy®, Ozempic®, Rybelsus®, Mounjaro®, or Saxenda®, or other GLP-1 brands, are informational only. Compounded and FDA-approved medications are not interchangeable.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists represent a class of medications primarily prescribed for type 2 diabetes management and, more recently, for chronic weight management. These drugs mimic the action of naturally occurring GLP-1, an incretin hormone released by the intestine in response to food intake. By binding to GLP-1 receptors throughout the body, these medications enhance glucose-dependent insulin secretion, suppress glucagon release, slow gastric emptying, and promote satiety.

Currently available GLP-1 receptor agonists in the United States include semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy, Rybelsus), dulaglutide (Trulicity), liraglutide (Victoza, Saxenda), exenatide (Byetta, Bydureon BCise), and tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Zepbound)—though tirzepatide is technically a dual GLP-1/GIP receptor agonist. The FDA has approved these agents for glycemic control in type 2 diabetes based on their demonstrated efficacy in lowering hemoglobin A1c levels by approximately 0.5–1.5%, depending on the specific agent and dose. Certain formulations have separate FDA approvals for chronic weight management (Wegovy, Saxenda, Zepbound), with higher-dose semaglutide and tirzepatide capable of producing 10–15% weight reduction, while other GLP-1 agents typically yield more modest weight loss.

These medications are administered via subcutaneous injection (with the exception of oral semaglutide) at varying frequencies from daily to weekly, depending on the specific formulation. Common adverse effects include gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation, which typically diminish over time. More serious but rare complications include pancreatitis and gallbladder disease. Importantly, these medications carry a boxed warning about thyroid C-cell tumors observed in rodent studies and are contraindicated in patients with personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) or Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia syndrome type 2 (MEN2). Understanding the full safety profile of GLP-1 medications, including potential effects on vision, remains essential for both prescribers and patients as use of these agents continues to expand rapidly across diverse patient populations.

The relationship between GLP-1 receptor agonists and eye problems is complex and requires careful interpretation of available evidence. There is no established direct causal mechanism by which GLP-1 medications damage ocular structures. However, clinical observations and trial data have identified specific circumstances where these drugs may be associated with worsening diabetic retinopathy, particularly in patients with pre-existing retinal disease.

The primary concern centers on the rapid reduction in blood glucose levels that GLP-1 medications can produce. When glycemic control improves too quickly, patients with existing diabetic retinopathy may experience paradoxical worsening of their retinal disease. This phenomenon, known as early worsening of diabetic retinopathy, has been documented with various diabetes treatments and is not unique to GLP-1 receptor agonists. The mechanism likely involves rapid changes in retinal blood flow, increased vascular permeability, and alterations in growth factor expression as glucose levels normalize.

It is important to emphasize that the risk of eye problems appears primarily concentrated in patients with pre-existing diabetic retinopathy who experience rapid glycemic improvement. The FDA label for semaglutide specifically includes a warning about diabetic retinopathy complications and advises monitoring in patients with a history of diabetic retinopathy. Most patients taking GLP-1 receptor agonists will not experience ocular complications, though rare reports of other eye conditions exist with uncertain causality. The highest risk appears to be in patients with type 2 diabetes who have established diabetic retinopathy at the time of treatment initiation, particularly when aggressive glycemic targets are pursued rapidly without appropriate ophthalmologic monitoring.

The association between GLP-1 receptor agonists and diabetic retinopathy progression gained significant attention following the SUSTAIN-6 trial, published in 2016. This cardiovascular outcomes trial of semaglutide versus placebo in patients with type 2 diabetes at high cardiovascular risk revealed an unexpected finding: patients receiving semaglutide experienced a statistically significant increase in diabetic retinopathy complications (hazard ratio 1.76, 95% CI 1.11–2.78, p=0.02). The composite endpoint included the need for retinal photocoagulation, treatment with intravitreal agents, vitreous hemorrhage, or diabetes-related blindness.

Subsequent analysis of SUSTAIN-6 data revealed that the increased risk was concentrated among patients who entered the trial with pre-existing diabetic retinopathy and experienced rapid improvements in glycemic control. Participants with baseline retinopathy who achieved substantial A1c reductions within the first 16 weeks of treatment faced the highest risk of progression. Importantly, patients without baseline retinopathy did not demonstrate increased risk, and the overall cardiovascular benefits of semaglutide were maintained despite this ocular safety signal.

Other GLP-1 receptor agonist trials have yielded mixed results regarding retinopathy risk. The LEADER trial with liraglutide and the REWIND trial with dulaglutide did not show significant increases in retinopathy complications, though differences in trial design, patient populations, baseline retinopathy prevalence, and rates of glycemic improvement may explain these discrepant findings. The SUSTAIN-6 findings led to updates in FDA labeling for semaglutide, noting that patients with a history of diabetic retinopathy should be monitored for progression. Current clinical practice considerations emphasize the importance of ophthalmologic screening before initiating GLP-1 therapy in patients with longstanding diabetes and implementing more gradual titration schedules in those with known retinal disease to minimize the risk of early worsening.

Beyond the specific concern about diabetic retinopathy progression, broader research into GLP-1 receptor agonists and ocular health has been limited but generally reassuring. Real-world observational studies examining clinical data have not identified consistent patterns of increased rates of general vision problems associated with GLP-1 use, though most studies were not specifically designed to detect rare ocular events. It's important to note that high-quality evidence regarding non-diabetic retinopathy eye conditions is still evolving.

Preclinical studies have demonstrated that GLP-1 receptors are expressed in various ocular tissues, including the retina, and may play roles in neuroprotection, inflammation modulation, and vascular regulation. Animal models have shown that GLP-1 receptor activation can reduce retinal inflammation, decrease oxidative stress, and protect retinal ganglion cells from apoptosis. These laboratory findings suggest potential protective mechanisms, though their clinical relevance in humans remains uncertain. The apparent contradiction between these potential protective mechanisms and clinical observations of retinopathy worsening likely reflects the complex interplay between rapid metabolic changes and pre-existing vascular damage.

Long-term follow-up data from cardiovascular outcomes trials indicate that any early increase in retinopathy events tends to plateau over time, and the overall trajectory of retinal health may ultimately be favorable due to sustained improvements in glycemic control. Post-hoc analyses suggest that after the initial period of rapid glucose lowering, retinopathy event rates became more similar between treatment groups. This pattern aligns with decades of diabetes research demonstrating that while rapid glycemic improvement carries short-term risks for retinopathy progression, sustained long-term glucose control reduces the incidence and severity of diabetic eye disease. Current evidence suggests that GLP-1 medications, when used with appropriate patient selection and monitoring, likely do not pose significant long-term threats to vision for most patients and may contribute to better overall ocular outcomes through improved metabolic control.

Patients prescribed GLP-1 receptor agonists can take several evidence-based steps to minimize any potential risks to their vision while maximizing the metabolic benefits of these medications. The American Diabetes Association recommends that adults with type 2 diabetes undergo comprehensive dilated eye examinations by an ophthalmologist or optometrist at the time of diabetes diagnosis. If no evidence of retinopathy is found and glycemic control is stable, examinations every 1-2 years may be considered. If retinopathy is present, more frequent examinations are needed based on severity.

For patients with known diabetic retinopathy who are candidates for GLP-1 therapy, additional precautions are warranted. Key protective strategies include:

Pre-treatment ophthalmologic evaluation: Establish baseline retinal status before initiating GLP-1 therapy, particularly in patients with diabetes duration exceeding 10 years or poor prior glycemic control

Individualized medication titration: Consider a more gradual dose escalation approach to avoid precipitous drops in blood glucose for patients with advanced diabetic retinopathy, in coordination with ophthalmology care

Appropriate monitoring: Discuss with your healthcare provider whether more frequent eye examinations are needed based on your individual risk factors and baseline retinal status

Prompt reporting of visual symptoms: Contact your healthcare provider immediately if you experience sudden vision loss, new or dense floaters, flashing lights, a "curtain" over your vision, eye pain with vision changes, or any sudden vision disturbance

Patients without pre-existing diabetic retinopathy can generally follow standard eye examination schedules and do not require additional ophthalmologic monitoring solely due to GLP-1 use. However, maintaining overall metabolic health through blood pressure control (target <130/80 mmHg if safely attainable, or <140/90 mmHg), lipid management, smoking cessation, and regular physical activity all contribute to reducing long-term diabetic eye disease risk. It is important to recognize that the cardiovascular and renal benefits of GLP-1 medications typically outweigh the potential for retinopathy progression in appropriately selected patients, and discontinuing these medications due to unfounded concerns about vision may result in worse overall health outcomes. Collaborative decision-making between patients, endocrinologists or primary care providers, and ophthalmologists ensures that GLP-1 therapy is implemented safely with appropriate safeguards for ocular health.

Semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy) may worsen diabetic retinopathy in patients with pre-existing retinal disease who experience rapid blood sugar improvements, but it does not directly damage eye structures. Patients without baseline diabetic retinopathy do not face increased vision risks.

Patients with type 2 diabetes who have established diabetic retinopathy at treatment initiation face the highest risk, particularly when experiencing rapid A1c reductions within the first 16 weeks of therapy. Those without pre-existing retinopathy are not at increased risk.

Patients with longstanding diabetes (over 10 years) or poor prior glycemic control should undergo comprehensive dilated eye examination before starting GLP-1 medications to establish baseline retinal status. Those with known diabetic retinopathy require pre-treatment ophthalmologic evaluation and closer monitoring.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.