LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

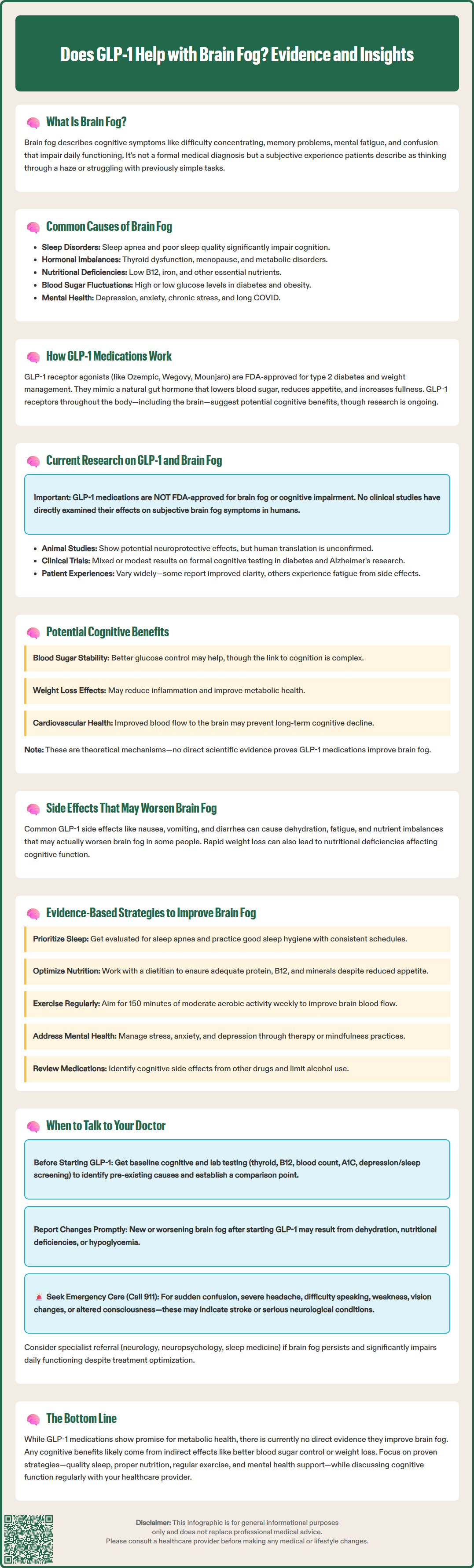

Does GLP-1 help with brain fog? Many patients taking GLP-1 receptor agonists for type 2 diabetes or weight management wonder whether these medications might improve cognitive symptoms like difficulty concentrating, memory problems, and mental fatigue. While GLP-1 medications are not FDA-approved for treating brain fog, emerging research suggests potential indirect cognitive benefits through improved blood sugar control, weight loss, and reduced inflammation. This article examines the current evidence on GLP-1 and brain fog, explores possible mechanisms, and provides guidance on managing cognitive symptoms while using these medications.

Quick Answer: GLP-1 receptor agonists are not FDA-approved for brain fog, and no direct clinical evidence confirms they improve these cognitive symptoms in humans.

We offer compounded medications and Zepbound®. Compounded medications are prepared by licensed pharmacies and are not FDA-approved. References to Wegovy®, Ozempic®, Rybelsus®, Mounjaro®, or Saxenda®, or other GLP-1 brands, are informational only. Compounded and FDA-approved medications are not interchangeable.

Brain fog is a colloquial term describing a constellation of cognitive symptoms rather than a formal medical diagnosis. Individuals experiencing brain fog typically report difficulty concentrating, memory problems, mental fatigue, and a sense of confusion or lack of mental clarity. These symptoms can significantly impair work performance, academic achievement, and daily functioning.

The subjective nature of brain fog makes it challenging to quantify, yet its impact on quality of life is substantial. Patients often describe feeling as though they are thinking through a haze, struggling to find words, or experiencing delayed mental processing. Tasks that previously required minimal effort may become exhausting, and multitasking becomes particularly difficult.

Brain fog is not a standalone condition but rather a symptom associated with numerous underlying causes. Common contributors include sleep disorders, chronic stress, hormonal imbalances (particularly thyroid dysfunction), nutritional deficiencies (such as vitamin B12 or iron), autoimmune conditions (like multiple sclerosis or lupus), medications, and metabolic disorders including diabetes. Depression, anxiety, chronic fatigue syndrome, post-COVID syndrome (long COVID), and menopause/perimenopause are also frequently associated with cognitive clouding.

For individuals with type 2 diabetes or obesity—conditions for which GLP-1 receptor agonists are prescribed—brain fog may stem from multiple sources. Both acute hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia can temporarily impair cognitive function. Additionally, insulin resistance, chronic inflammation, and the psychological burden of managing chronic disease can all contribute to cognitive symptoms. Understanding these connections is essential when evaluating whether GLP-1 medications might influence brain fog symptoms.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists are a class of medications approved by the FDA for treating type 2 diabetes and, in some formulations, for chronic weight management. Common medications in this class include semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy, Rybelsus), dulaglutide (Trulicity), liraglutide (Victoza, Saxenda), and tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Zepbound), though tirzepatide is technically a dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist.

These medications work by mimicking the action of naturally occurring GLP-1, an incretin hormone released by the intestines in response to food intake. The primary mechanisms of action include:

Enhanced insulin secretion: GLP-1 receptor agonists stimulate glucose-dependent insulin release from pancreatic beta cells, meaning insulin is released only when blood glucose levels are elevated, reducing hypoglycemia risk when used as monotherapy (though risk increases when combined with insulin or sulfonylureas).

Suppressed glucagon secretion: They inhibit glucagon release from pancreatic alpha cells, decreasing hepatic glucose production.

Delayed gastric emptying: These medications slow the rate at which food leaves the stomach, contributing to improved postprandial glucose control and increased satiety, though this effect may diminish over time with some agents.

Central appetite regulation: GLP-1 receptors in the brain, particularly in areas regulating appetite and reward, are activated, leading to reduced food intake and body weight.

GLP-1 receptors are distributed throughout the body, including in the pancreas, gastrointestinal tract, heart, kidneys, and notably, the central nervous system. This widespread distribution has prompted research into potential effects beyond glucose control, including neuroprotective and cognitive benefits. The presence of GLP-1 receptors in brain regions involved in learning, memory, and cognition has generated particular interest in whether these medications might influence cognitive function.

Important safety considerations include a boxed warning for medullary thyroid carcinoma risk and contraindication in patients with Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia syndrome type 2 (MEN2). These medications also carry risks of pancreatitis and gallbladder disease, and are not recommended in patients with severe gastrointestinal disease.

There is currently no direct clinical evidence specifically examining whether GLP-1 receptor agonists improve subjective brain fog symptoms in humans. The term "brain fog" itself is not a standardized clinical endpoint in research studies, making it difficult to draw definitive conclusions. It's important to note that GLP-1 medications are not FDA-approved for treating cognitive impairment or brain fog, and should not be prescribed specifically for these indications.

Preclinical studies in animal models have demonstrated neuroprotective effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists. These include reduced neuroinflammation, decreased oxidative stress, enhanced neuronal survival, and improved synaptic plasticity. Some research has shown potential benefits in models of Alzheimer's disease and other neurodegenerative conditions, though translating these findings to human cognitive symptoms remains uncertain.

Clinical trials evaluating GLP-1 medications for diabetes and obesity have not systematically assessed brain fog as a primary outcome. Some studies have examined formal cognitive testing, with mixed results. The REWIND trial's cognitive substudy with dulaglutide and smaller trials of liraglutide in Alzheimer's disease have shown modest or inconsistent effects. Ongoing research, including the semaglutide EVOKE trials in Alzheimer's disease, may provide more definitive evidence. However, these studies typically use standardized neuropsychological tests rather than measuring subjective cognitive complaints like brain fog.

Anecdotal reports from patients taking GLP-1 medications vary considerably. Some individuals report improved mental clarity, which may relate to better glycemic control, weight loss, reduced inflammation, or improved sleep quality. Conversely, others report fatigue or cognitive symptoms, potentially related to rapid weight loss, nutritional changes, or medication side effects. The heterogeneity of these experiences underscores the complexity of attributing cognitive changes directly to GLP-1 receptor agonism versus the multiple physiological changes these medications induce.

While direct evidence for brain fog improvement is lacking, several mechanisms suggest GLP-1 medications could theoretically influence cognitive function. Understanding these pathways helps contextualize potential benefits and guides realistic expectations.

Improved glycemic control represents a primary mechanism. Chronic hyperglycemia and glycemic variability are associated with cognitive impairment in individuals with diabetes. By stabilizing blood glucose levels, GLP-1 receptor agonists may reduce glucose-related cognitive fluctuations. However, the relationship between improved glycemic control and cognitive function is complex, as demonstrated by mixed results in large trials like ACCORD-MIND. Hypoglycemia, which can impair cognition, is uncommon with GLP-1 monotherapy but risk increases when combined with insulin or sulfonylureas.

Weight loss and metabolic improvement may contribute to cognitive benefits. Obesity is associated with chronic low-grade inflammation, insulin resistance, and altered brain structure and function. Weight reduction achieved through GLP-1 therapy may improve metabolic health and reduce systemic inflammation. However, the Look AHEAD trial and other studies examining intentional weight loss and cognition have shown variable results, suggesting this relationship is not straightforward.

Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular benefits may play a role. Specific GLP-1 receptor agonists (liraglutide, semaglutide, dulaglutide) have demonstrated cardiovascular benefits in clinical trials, including reduced risk of major adverse cardiovascular events. Improved vascular health may enhance cerebral blood flow and reduce risk of vascular cognitive impairment, though this represents a long-term preventive effect rather than immediate symptom relief.

Common adverse effects of GLP-1 medications must also be considered when evaluating cognitive impacts. Gastrointestinal symptoms—including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation—are frequent, particularly during dose escalation. These symptoms, along with reduced caloric intake, may cause fatigue, dehydration, or electrolyte imbalances that could paradoxically worsen brain fog in some individuals. Monitoring for adequate nutrition, hydration, and electrolyte balance is essential during treatment.

Addressing brain fog requires a comprehensive approach that considers multiple contributing factors beyond any single medication. For individuals with diabetes or obesity considering or taking GLP-1 medications, several evidence-based strategies may help improve cognitive symptoms.

Optimizing sleep quality is fundamental to cognitive function. Sleep disorders, including obstructive sleep apnea (common in obesity), insomnia, and insufficient sleep duration, significantly impair concentration, memory, and mental clarity. Evaluation for sleep disorders and implementation of good sleep hygiene practices—consistent sleep schedule, dark and cool bedroom environment, limiting screen time before bed—are essential first steps.

Nutritional adequacy becomes particularly important during GLP-1 therapy. The appetite suppression and reduced food intake associated with these medications may lead to inadequate protein, vitamin, and mineral consumption. Deficiencies in vitamin B12 (particularly in patients also taking metformin), iron, and other nutrients have been linked to cognitive symptoms. Working with a registered dietitian to ensure nutrient-dense food choices within reduced caloric intake can help prevent deficiency-related brain fog. While vitamin D deficiency and low omega-3 levels have been associated with cognitive complaints, evidence for supplementation in the absence of deficiency remains limited.

Physical activity has well-established cognitive benefits. Regular aerobic exercise improves cerebral blood flow, promotes neuroplasticity, reduces inflammation, and enhances mood. The American Diabetes Association recommends at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity weekly for individuals with diabetes, with additional benefits from resistance training.

Stress management and mental health warrant attention. Chronic stress, anxiety, and depression profoundly affect cognitive function. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, mindfulness practices, and, when appropriate, psychiatric medication can address these contributors to brain fog. The psychological aspects of managing chronic disease should not be overlooked.

Medication review is prudent, as numerous medications can cause cognitive side effects. Sedating antihistamines, certain blood pressure medications, anticholinergic drugs, and others may contribute to mental cloudiness. Limiting alcohol and cannabis use can also improve cognitive clarity. A comprehensive medication review with a healthcare provider can identify potential culprits.

Adequate hydration is often overlooked but essential for optimal brain function. Maintaining proper fluid intake, especially during GLP-1 therapy when gastrointestinal symptoms may affect hydration status, is important for cognitive performance.

Patients experiencing brain fog should engage in open communication with their healthcare providers, particularly when considering or currently taking GLP-1 medications. Several scenarios warrant medical evaluation and discussion.

Before starting GLP-1 therapy, discuss existing cognitive symptoms with your physician. A baseline assessment helps distinguish pre-existing brain fog from any changes that might occur after medication initiation. Your provider should evaluate potential underlying causes, including thyroid function tests, vitamin B12 levels (especially if you take metformin), complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, A1C, and screening for depression or sleep disorders. This workup establishes whether brain fog stems from potentially reversible causes that require specific treatment.

New or worsening cognitive symptoms after starting a GLP-1 medication require prompt evaluation. While these medications are not typically associated with cognitive impairment, individual responses vary. Severe nausea, vomiting, or reduced oral intake may lead to dehydration or electrolyte imbalances that manifest as confusion or difficulty concentrating. Rapid weight loss may occasionally be associated with nutritional deficiencies. If you take insulin or sulfonylureas with GLP-1 therapy, check your blood glucose when experiencing cognitive symptoms, as hypoglycemia can mimic brain fog. Your provider can assess whether symptoms relate to medication side effects, inadequate nutrition, or other factors.

Red flag symptoms necessitate urgent medical attention. Sudden confusion, severe headache, difficulty speaking, weakness, vision changes, or altered consciousness may indicate serious conditions such as stroke, severe hypoglycemia, or other neurological emergencies. Call 911 immediately if you experience these symptoms, as they require immediate evaluation and are not attributable to typical brain fog.

Monitoring and follow-up should include discussion of cognitive function alongside traditional diabetes and weight management metrics. The American Diabetes Association guidelines emphasize individualized care that considers quality of life and patient-reported outcomes. If brain fog significantly impairs daily functioning despite GLP-1 therapy and optimization of other factors, your provider may consider alternative treatment approaches or additional investigations. Referral to neurology, neuropsychology, sleep medicine, endocrinology, or psychiatry may be appropriate for persistent, unexplained cognitive symptoms that do not respond to initial interventions.

No, GLP-1 receptor agonists are not FDA-approved for treating cognitive impairment or brain fog. They are approved only for type 2 diabetes management and chronic weight management in specific formulations.

Gastrointestinal symptoms including nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea are most common, particularly during dose escalation. These effects, along with reduced food intake, may cause dehydration or nutritional deficiencies that could worsen brain fog in some individuals.

Contact your doctor if you experience new or worsening cognitive symptoms after starting GLP-1 therapy, especially if accompanied by severe nausea, dehydration, or signs of hypoglycemia. Seek emergency care immediately for sudden confusion, severe headache, difficulty speaking, or vision changes.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.