LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

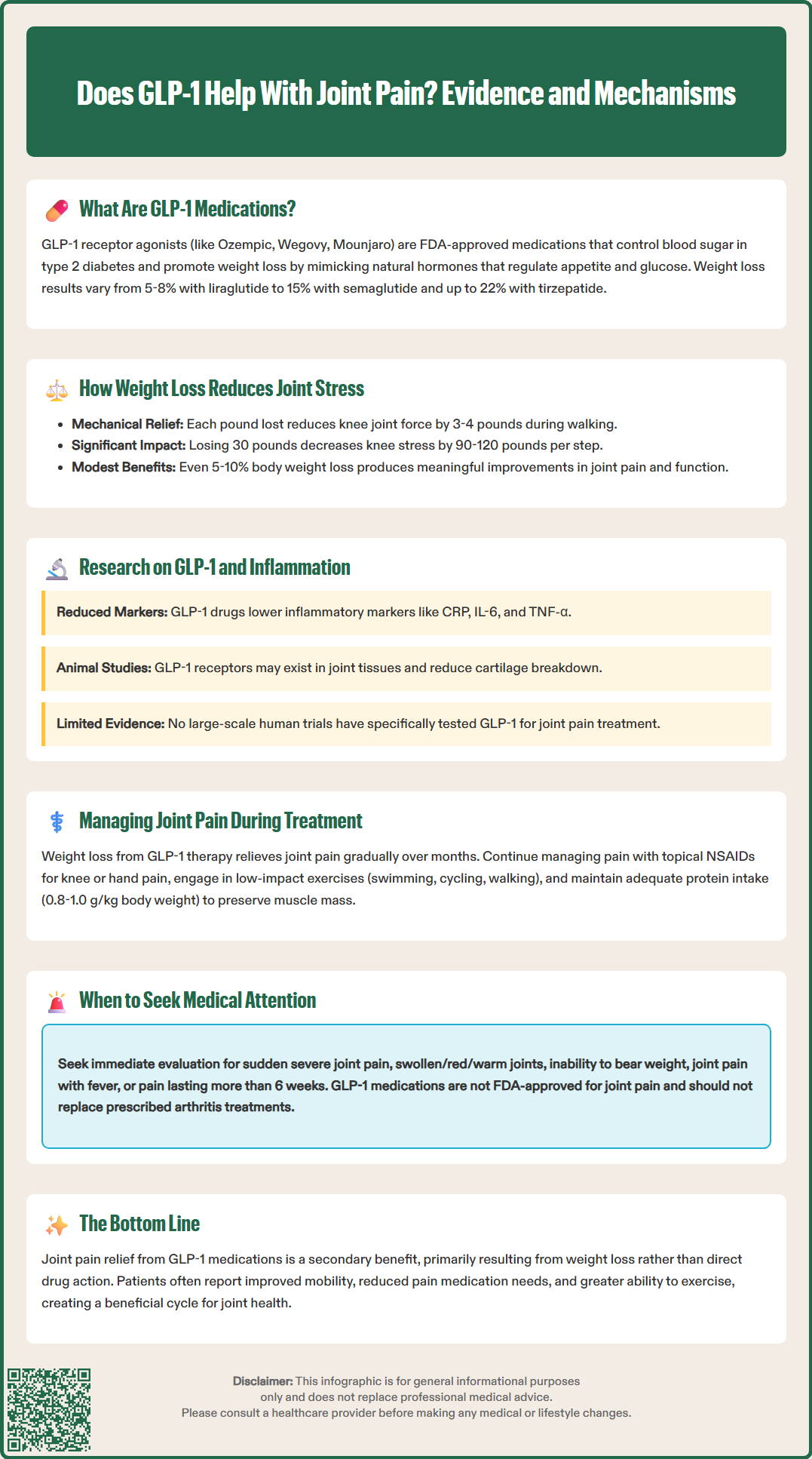

Many patients taking GLP-1 receptor agonists for diabetes or weight management report improvements in joint pain, prompting questions about whether these medications directly address musculoskeletal symptoms. While GLP-1 drugs like semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy) and tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Zepbound) are not FDA-approved for joint pain treatment, emerging evidence suggests they may provide indirect benefits through substantial weight loss. Understanding the relationship between GLP-1 therapy and joint symptom relief requires examining both biomechanical effects of weight reduction and potential anti-inflammatory properties. This article explores current research on GLP-1 medications and joint pain, helping patients and clinicians set appropriate expectations for musculoskeletal outcomes during treatment.

Quick Answer: GLP-1 medications may help reduce joint pain primarily through significant weight loss that decreases mechanical stress on weight-bearing joints, though they are not FDA-approved for this purpose.

We offer compounded medications and Zepbound®. Compounded medications are prepared by licensed pharmacies and are not FDA-approved. References to Wegovy®, Ozempic®, Rybelsus®, Mounjaro®, or Saxenda®, or other GLP-1 brands, are informational only. Compounded and FDA-approved medications are not interchangeable.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists represent a class of medications originally developed for type 2 diabetes management and now widely prescribed for chronic weight management. These agents include semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy), dulaglutide (Trulicity), and liraglutide (Victoza, Saxenda). Tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Zepbound) is a dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist with similar clinical effects. These medications work by mimicking naturally occurring hormones that regulate blood glucose and appetite.

The primary mechanism of action involves stimulating insulin secretion in a glucose-dependent manner, suppressing glucagon release, slowing gastric emptying, and promoting satiety through central nervous system pathways. According to FDA labeling, these medications are indicated for improving glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes and, in higher doses for certain formulations, for chronic weight management in adults with obesity or overweight with at least one weight-related comorbidity. Wegovy is also approved for adolescents aged 12 and older with obesity.

Clinical trials have demonstrated varying efficacy across the class, with weight reductions ranging from approximately 5-8% with liraglutide 3 mg to 15% with semaglutide 2.4 mg and 10-22% with tirzepatide, depending on dose. Common adverse effects include gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation, which typically diminish with gradual dose titration. More serious risks include pancreatitis, gallbladder disease, acute kidney injury, and a boxed warning for thyroid C-cell tumors (with a contraindication in patients with personal/family history of MTC or MEN2). Semaglutide carries a warning about diabetic retinopathy complications, and all agents can cause hypoglycemia when used with insulin or sulfonylureas.

While joint pain relief is not an FDA-approved indication for GLP-1 medications, emerging clinical observations and patient reports have prompted investigation into potential musculoskeletal benefits. Understanding whether these effects are direct pharmacological actions or secondary to weight loss remains an important clinical question.

There is no official FDA-approved indication for GLP-1 receptor agonists in treating joint pain, and these medications are not classified as analgesics or anti-inflammatory agents. However, clinical observations and patient-reported outcomes from weight loss trials have documented improvements in joint symptoms among individuals taking these medications. The relationship between GLP-1 therapy and joint pain relief appears to be multifactorial rather than a direct pharmacological effect on joint tissues.

The most established connection involves mechanical stress reduction on weight-bearing joints. Obesity significantly increases loading forces on the knees, hips, ankles, and spine, accelerating cartilage degradation and contributing to osteoarthritis development and progression. According to the Arthritis Foundation and CDC resources, each pound of body weight translates to approximately 3-4 pounds of force across the knee joint during walking. When patients achieve substantial weight loss through GLP-1 therapy, the biomechanical burden on these joints decreases proportionally. This mechanical unloading can translate into meaningful symptom improvement, as supported by the American College of Rheumatology guidelines.

Additionally, preclinical research suggests GLP-1 receptors may be present in various tissues beyond the pancreas and brain, including synovial tissue and chondrocytes. While the clinical significance remains uncertain, this raises the theoretical possibility of direct anti-inflammatory or chondroprotective effects. Some studies have shown reductions in systemic inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) in patients taking GLP-1 medications, though whether this translates to clinically meaningful joint pain reduction independent of weight loss is not definitively established.

Patients considering GLP-1 therapy should understand that any joint pain improvement is likely a secondary benefit rather than a primary therapeutic target. Those with significant joint disease should continue appropriate orthopedic or rheumatologic care while pursuing weight management strategies.

The biomechanical relationship between body weight and joint loading provides a clear physiological basis for understanding how GLP-1-induced weight loss may alleviate joint pain. Research indicates that each pound of body weight translates to approximately 3-4 pounds of force across the knee joint during walking and even greater forces during activities like stair climbing or running. Consequently, a 30-pound weight loss could reduce knee loading by 90-120 pounds with each step, representing substantial mechanical relief.

Osteoarthritis, the most common form of joint disease, is strongly associated with obesity. Excess weight accelerates cartilage breakdown through increased mechanical stress and contributes to a pro-inflammatory state that may further damage joint structures. The American College of Rheumatology guidelines emphasize weight loss as a core non-pharmacological intervention for overweight and obese patients with knee osteoarthritis, with evidence supporting that even modest weight reduction (5-10% of body weight) can produce clinically meaningful improvements in pain and function.

GLP-1 medications facilitate weight loss primarily through reducing appetite and caloric intake and slowing gastric emptying to prolong satiety. Unlike dietary interventions alone, which often result in weight regain, GLP-1 therapy can help maintain weight loss as long as treatment continues. However, clinical trials such as STEP-4 demonstrate that weight regain typically occurs after discontinuation of therapy. This sustained weight reduction while on treatment may provide ongoing joint protection and symptom relief.

Clinical trials of GLP-1 medications, including the STEP program for semaglutide and SURMOUNT trials for tirzepatide, have documented improvements in physical function scores and quality of life measures. While these trials were not specifically designed to assess joint pain, patients with obesity-related joint pain who achieve significant weight loss through GLP-1 therapy often report improved mobility, reduced need for analgesics, and enhanced ability to engage in physical activity—creating a positive cycle of further weight management and joint health.

Beyond mechanical effects, emerging evidence suggests GLP-1 receptor agonists may exert anti-inflammatory properties that could theoretically benefit joint health. Obesity is characterized by chronic low-grade systemic inflammation, with elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and C-reactive protein. This inflammatory milieu contributes to insulin resistance, cardiovascular disease, and potentially to joint inflammation and cartilage degradation.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials have found that GLP-1 receptor agonists significantly decreased CRP levels compared to placebo or other diabetes medications. Similar reductions have been observed for other inflammatory biomarkers. However, it remains uncertain whether these changes result from direct anti-inflammatory effects of GLP-1 receptor activation or are secondary to weight loss and improved metabolic health.

Preclinical research in animal models has identified GLP-1 receptors in synovial tissue, cartilage, and bone, suggesting potential for direct effects on joint structures. Some laboratory studies have shown that GLP-1 analogs may reduce cartilage degradation and synovial inflammation in experimental arthritis models. Certain preclinical investigations indicate GLP-1 may inhibit inflammatory signaling pathways and reduce oxidative stress in joint tissues. Nevertheless, translating these laboratory findings to clinical joint pain relief in humans requires further investigation.

Currently, there are no large-scale clinical trials specifically designed to evaluate GLP-1 medications for joint pain or osteoarthritis treatment. Most evidence comes from secondary analyses of diabetes and obesity trials where joint symptoms were not primary endpoints. While the anti-inflammatory properties of GLP-1 therapy are promising, clinicians should counsel patients that definitive evidence for direct joint pain relief independent of weight loss is lacking. Patients with inflammatory arthritis conditions should continue disease-modifying treatments as prescribed by their rheumatologist.

Patients initiating GLP-1 therapy for diabetes or weight management who also experience joint pain should maintain a comprehensive approach to musculoskeletal health. While weight loss may provide significant joint symptom relief over time, this benefit typically emerges gradually over months as weight reduction accumulates. During this period, appropriate joint pain management remains essential for maintaining quality of life and physical function.

In alignment with American College of Rheumatology and American College of Physicians guidelines, first-line management for osteoarthritis includes exercise and weight loss. For pharmacological management, topical NSAIDs are strongly recommended as initial therapy for knee or hand osteoarthritis. Oral NSAIDs such as ibuprofen or naproxen may be appropriate for moderate pain when used at the lowest effective dose for the shortest duration necessary, particularly in patients without cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, or gastrointestinal risk factors. Acetaminophen offers limited benefit but may be considered for some patients. For persistent symptoms, intra-articular corticosteroid injections or duloxetine may be appropriate adjunctive therapies.

Physical therapy and structured exercise programs represent crucial non-pharmacological interventions. Strengthening exercises for muscles surrounding affected joints can improve stability and reduce pain, while low-impact aerobic activities such as swimming, cycling, or walking support both weight loss and joint health. As patients lose weight on GLP-1 therapy, increased mobility often becomes feasible, creating opportunities for enhanced physical activity that further supports weight management and joint function.

Key management considerations include:

Continuing prescribed arthritis medications (disease-modifying agents, corticosteroids) as directed

Monitoring for new or worsening joint symptoms that may require evaluation

Maintaining adequate protein intake (generally 0.8-1.0 g/kg body weight, individualized based on age and kidney function) to preserve muscle mass during weight loss

Ensuring sufficient calcium and vitamin D for bone health

Reporting severe joint pain, swelling, or functional limitation promptly

Patients should seek medical evaluation if they experience sudden onset of severe joint pain, joint swelling with redness or warmth, inability to bear weight, joint symptoms accompanied by fever, or persistent pain lasting more than 6 weeks. While joint pain is not a common adverse effect of GLP-1 medications, arthralgia can occur, and any new or worsening musculoskeletal symptoms warrant appropriate clinical assessment. Collaboration between primary care providers, endocrinologists, and orthopedic or rheumatology specialists ensures comprehensive care addressing both metabolic health and joint function.

No, GLP-1 receptor agonists are not FDA-approved for joint pain treatment. They are indicated for type 2 diabetes management and chronic weight management, though patients may experience joint symptom improvements as a secondary benefit of weight loss.

Weight loss reduces mechanical stress on weight-bearing joints, with each pound lost decreasing knee loading by approximately 3-4 pounds during walking. This biomechanical relief can lead to meaningful improvements in osteoarthritis symptoms and physical function over time.

No, patients should continue prescribed arthritis medications and maintain comprehensive joint care as directed by their healthcare providers. GLP-1 therapy should complement, not replace, appropriate orthopedic or rheumatologic treatment for joint conditions.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.