LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

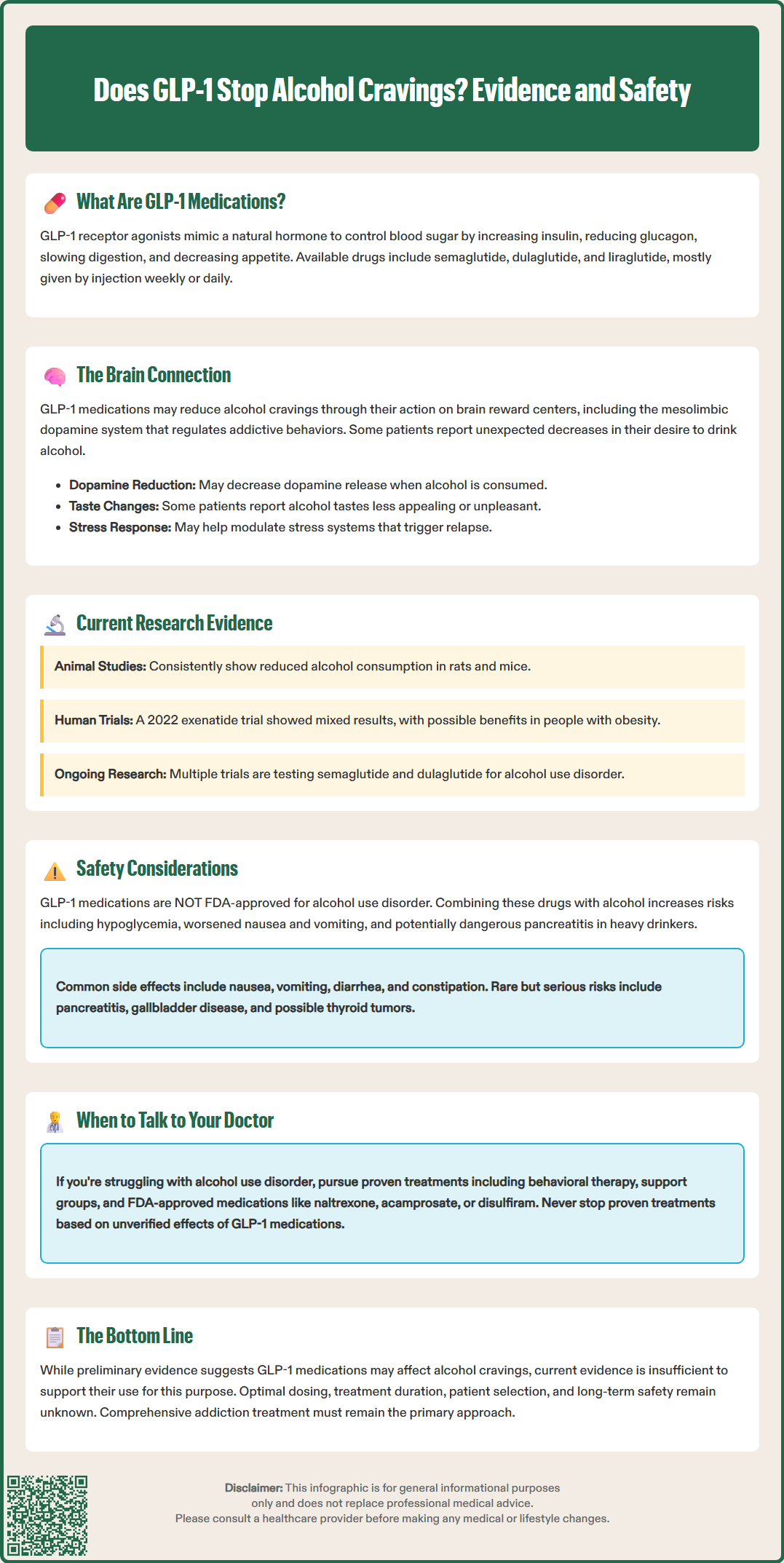

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, FDA-approved medications for type 2 diabetes and weight management, have recently sparked interest for an unexpected effect: some patients report reduced desire to drink alcohol while taking these drugs. Does GLP-1 stop alcohol cravings? While anecdotal reports and preliminary research suggest a potential connection between GLP-1 medications and decreased alcohol consumption, these agents are not FDA-approved for treating alcohol use disorder. This article examines the emerging evidence, proposed mechanisms involving brain reward pathways, and important safety considerations for clinicians and patients navigating this investigational area.

Quick Answer: GLP-1 receptor agonists may reduce alcohol cravings in some individuals, but they are not FDA-approved for treating alcohol use disorder and evidence remains preliminary.

We offer compounded medications and Zepbound®. Compounded medications are prepared by licensed pharmacies and are not FDA-approved. References to Wegovy®, Ozempic®, Rybelsus®, Mounjaro®, or Saxenda®, or other GLP-1 brands, are informational only. Compounded and FDA-approved medications are not interchangeable.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists are a class of medications originally developed to manage type 2 diabetes mellitus. These agents mimic the action of naturally occurring GLP-1, an incretin hormone released from the intestinal L-cells in response to food intake. The physiologic role of GLP-1 includes stimulating glucose-dependent insulin secretion, suppressing glucagon release, slowing gastric emptying, and promoting satiety through central nervous system pathways.

FDA-approved GLP-1 receptor agonists include semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy, Rybelsus), dulaglutide (Trulicity), liraglutide (Victoza, Saxenda), lixisenatide (Adlyxin), exenatide (Bydureon BCise), and tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Zepbound)—though tirzepatide is technically a dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist. Most are administered via subcutaneous injection, with dosing frequencies ranging from daily to weekly depending on the specific formulation. Oral semaglutide (Rybelsus) is the only FDA-approved oral GLP-1 receptor agonist.

Beyond glycemic control, certain GLP-1 receptor agonists have demonstrated significant benefits in weight management, cardiovascular risk reduction, and renal protection in patients with type 2 diabetes, though these benefits vary by specific agent. Semaglutide and liraglutide have received FDA approval specifically for chronic weight management in adults with obesity or overweight with at least one weight-related comorbidity. The American Diabetes Association recommends specific GLP-1 receptor agonists as preferred agents for patients with type 2 diabetes who have established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or indicators of high cardiovascular risk.

Common adverse effects include gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation, which typically diminish with continued use. More serious but rare complications include pancreatitis, gallbladder disease, and potential thyroid C-cell tumors (observed in rodent studies, with uncertain human relevance). Additional safety considerations include caution in patients with severe gastroparesis, and a potential risk of diabetic retinopathy complications with rapid glucose improvement, particularly with semaglutide.

The potential relationship between GLP-1 receptor agonists and alcohol consumption has emerged from both preclinical research and anecdotal clinical observations. GLP-1 receptors are widely distributed throughout the central nervous system, including brain regions involved in reward processing, motivation, and addictive behaviors—particularly the mesolimbic dopamine system, which includes the ventral tegmental area and nucleus accumbens.

Patients prescribed GLP-1 medications for diabetes or weight management have reported unexpected reductions in their desire to consume alcohol, with some describing a complete loss of interest in drinking. These anecdotal reports, which constitute low-level evidence, have gained considerable attention on social media platforms and in patient communities, prompting scientific investigation into whether these observations represent a genuine pharmacologic effect or coincidental behavioral changes associated with improved metabolic health and weight loss.

It is important to emphasize that there is currently no FDA-approved indication for GLP-1 receptor agonists in the treatment of alcohol use disorder (AUD). The connection remains investigational, and any effects on alcohol consumption should be considered preliminary findings requiring rigorous clinical validation. The mechanisms underlying these reported effects likely involve complex interactions between metabolic signaling, central reward pathways, and potentially altered taste preferences or hedonic responses to alcohol.

Clinicians should be aware of these emerging reports when counseling patients, particularly those with comorbid metabolic conditions and problematic alcohol use. While GLP-1 medications are not recommended solely for alcohol cravings outside research settings, if prescribed for approved indications, patients should be counseled on the limited evidence and monitored appropriately.

Preclinical studies in rodent models have consistently demonstrated that GLP-1 receptor agonists reduce voluntary alcohol intake and preference. Research published in neuroscience journals has shown that administration of exenatide, liraglutide, and semaglutide decreases alcohol consumption in alcohol-preferring rats and mice, with effects observed across various experimental paradigms including two-bottle choice tests and operant self-administration models.

Human research remains limited but is expanding. A randomized clinical trial of once-weekly exenatide for alcohol use disorder published in JAMA Psychiatry (2022) did not meet its primary endpoint of reducing heavy drinking days in the overall study population. However, exploratory analyses suggested potential benefits in participants with obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m²). A small observational study published in JCI Insight (2022) examined individuals with obesity receiving semaglutide who reported reductions in alcohol intake, though the relationship to weight loss requires further investigation in controlled trials.

Several ongoing clinical trials are specifically examining GLP-1 receptor agonists for alcohol use disorder. These include studies evaluating semaglutide and dulaglutide in individuals with AUD, with primary outcomes measuring changes in drinking patterns, craving intensity, and alcohol-related consequences. Researchers are also investigating whether the effects differ based on baseline drinking severity, metabolic status, and genetic factors related to GLP-1 receptor expression and function.

Despite these preliminary findings, substantial uncertainty remains. The optimal dosing, duration of treatment, patient selection criteria, and long-term efficacy and safety for this potential indication are unknown. Current evidence does not support routine clinical use of GLP-1 medications specifically for alcohol cravings, and patients with alcohol use disorder should be referred to evidence-based treatments including behavioral interventions, mutual support groups, and FDA-approved pharmacotherapies such as naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram.

The neurobiological mechanisms by which GLP-1 receptor agonists might influence alcohol consumption involve complex interactions within brain reward circuitry. GLP-1 receptors are expressed in several key regions implicated in addiction and reward processing, including the ventral tegmental area (VTA), nucleus accumbens, amygdala, hippocampus, and lateral hypothalamus. These areas form interconnected networks that regulate motivated behavior, hedonic responses, and the reinforcing properties of both natural rewards and substances of abuse.

Preclinical studies suggest that GLP-1 receptor activation in the mesolimbic dopamine system appears to modulate dopamine signaling, which is central to the rewarding effects of alcohol and other addictive substances. Rodent research indicates that GLP-1 agonists may reduce dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens in response to alcohol, thereby potentially diminishing its rewarding properties. Additionally, GLP-1 signaling may influence GABAergic and glutamatergic neurotransmission, further modulating reward-related neural activity.

Beyond direct effects on reward pathways, GLP-1 receptor agonists may alter alcohol consumption through putative effects on stress response systems, including the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Stress and negative emotional states are significant triggers for alcohol craving and relapse in individuals with alcohol use disorder. By potentially modulating stress reactivity and improving mood regulation, GLP-1 medications might indirectly reduce alcohol-seeking behavior.

Another proposed mechanism involves changes in taste perception and palatability. Some patients report that alcohol tastes less appealing or even unpleasant while taking GLP-1 medications. This altered hedonic response could reflect changes in gustatory processing or central integration of taste and reward signals. The delayed gastric emptying caused by GLP-1 agonists might theoretically contribute to reduced alcohol consumption by altering absorption kinetics and the subjective experience of intoxication, though this hypothesis requires human pharmacokinetic studies for validation.

Clinicians must recognize that GLP-1 receptor agonists are not FDA-approved for treating alcohol use disorder or reducing alcohol cravings. Current approved indications are limited to type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic weight management (for specific agents at designated doses). While off-label prescribing is legally permissible in the US, it should be approached with caution, informed consent, and appropriate monitoring when considering these medications for patients with problematic alcohol use.

Patients with alcohol use disorder may have unique safety considerations when using GLP-1 medications. Alcohol consumption can affect glycemic control, and the combination of GLP-1 therapy with alcohol might increase hypoglycemia risk, particularly in patients taking concomitant insulin or sulfonylureas. Gastrointestinal adverse effects of GLP-1 agonists—including nausea, vomiting, and dehydration—could be exacerbated by alcohol use and may complicate medication adherence.

The risk of pancreatitis associated with GLP-1 receptor agonists warrants particular attention in patients with heavy alcohol consumption, as chronic alcohol use is itself a significant risk factor for both acute and chronic pancreatitis. Additional safety considerations include caution in patients with severe gastroparesis, gallbladder disease, and a potential risk of diabetic retinopathy complications with rapid glucose improvement (particularly with semaglutide). Patients with a personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma or multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2 should not receive GLP-1 medications due to the theoretical risk of thyroid C-cell tumors.

Appropriate clinical management for patients with comorbid metabolic conditions and problematic alcohol use should include:

Comprehensive assessment of alcohol consumption patterns using validated screening tools (AUDIT, AUDIT-C)

Referral to addiction medicine specialists or behavioral health providers for evidence-based AUD treatment, especially with red flags such as history of severe withdrawal, seizures, delirium tremens, pregnancy, severe liver disease, or suicidality

Consideration of FDA-approved pharmacotherapies for alcohol use disorder (naltrexone, acamprosate, disulfiram) with attention to their specific contraindications

If GLP-1 therapy is indicated for diabetes or obesity, close monitoring for changes in alcohol consumption and related behaviors

Patient education emphasizing that any effects on alcohol cravings are not established therapeutic benefits

Regular follow-up to assess medication adherence, adverse effects, and overall treatment response

Patients should never discontinue evidence-based treatments for alcohol use disorder in favor of unproven approaches. Any observed reductions in alcohol consumption while taking GLP-1 medications should be discussed with healthcare providers, and comprehensive addiction treatment should remain the standard of care.

No, GLP-1 receptor agonists are not FDA-approved for treating alcohol use disorder or reducing alcohol cravings. Their approved indications are limited to type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic weight management for specific agents at designated doses.

Preclinical studies in rodents consistently show reduced alcohol intake with GLP-1 medications, but human clinical trials have produced mixed results. A 2022 randomized trial of exenatide did not meet its primary endpoint for reducing heavy drinking days in the overall population, though exploratory analyses suggested potential benefits in participants with obesity.

GLP-1 receptors are located in brain reward regions including the ventral tegmental area and nucleus accumbens. Activation of these receptors may modulate dopamine signaling, potentially reducing alcohol's rewarding properties, though the exact mechanisms in humans remain under investigation.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.