LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

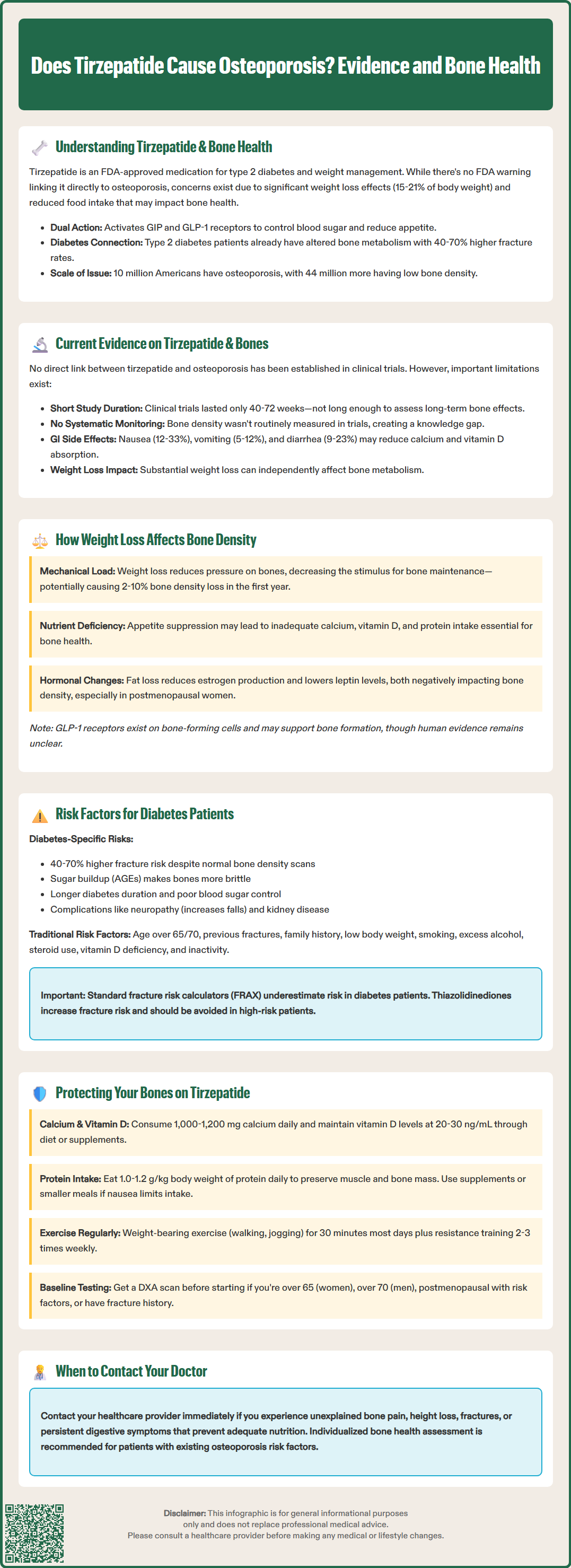

Does tirzepatide cause osteoporosis? This question concerns many patients starting Mounjaro or Zepbound for type 2 diabetes or weight management. Tirzepatide is a dual GIP and GLP-1 receptor agonist that produces significant weight loss, raising questions about potential effects on bone health. While clinical trials have not identified osteoporosis as a documented risk of tirzepatide, the medication's substantial metabolic effects and rapid weight reduction warrant careful consideration of skeletal health. Understanding the current evidence, mechanisms linking weight loss to bone density, and strategies to protect bone health helps patients and clinicians make informed treatment decisions.

Quick Answer: Current clinical trial data and FDA labeling show no established direct link between tirzepatide and osteoporosis.

Tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Zepbound) is a dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist approved by the FDA for type 2 diabetes management and chronic weight management. As this medication gains widespread use, patients and clinicians are increasingly asking about potential effects on bone health, particularly whether tirzepatide causes osteoporosis.

Osteoporosis is a systemic skeletal disorder characterized by low bone mass and microarchitectural deterioration of bone tissue, leading to increased bone fragility and fracture risk. The condition affects approximately 10 million Americans, with another 44 million having low bone density (osteopenia), according to the Bone Health and Osteoporosis Foundation. Concerns about tirzepatide and bone health arise from several factors: the medication's significant weight loss effects, reduced food intake due to appetite suppression, and the complex relationship between diabetes, obesity, and skeletal health.

Patients with type 2 diabetes already face altered bone metabolism compared to the general population. While they often have normal or even elevated bone mineral density (BMD), they paradoxically experience higher fracture rates. This creates a unique clinical context when introducing medications that cause substantial weight loss. Understanding whether tirzepatide specifically contributes to osteoporosis risk requires examining clinical trial data, mechanistic considerations, and the broader effects of weight loss on skeletal integrity. Currently, there is no official FDA warning linking tirzepatide directly to osteoporosis, but the question merits careful clinical consideration given the medication's metabolic effects.

Based on available clinical trial data and FDA labeling, there is no established direct causal link between tirzepatide and osteoporosis. The pivotal SURPASS clinical trial program for type 2 diabetes and the SURMOUNT trials for weight management did not identify osteoporosis or significant bone density loss as adverse events associated with tirzepatide use. The FDA prescribing information for both Mounjaro and Zepbound does not list osteoporosis, bone loss, or fractures as known risks of the medication.

However, the absence of a documented association does not mean the question is fully resolved. Most tirzepatide trials have followed patients for 40-72 weeks, which may be insufficient to detect gradual bone density changes that typically develop over years. Bone mineral density assessments were not primary or secondary endpoints in the major tirzepatide trials, meaning systematic bone health monitoring was not conducted across the study populations. This represents a knowledge gap rather than definitive reassurance.

What we do know is that tirzepatide causes substantial weight loss—averaging 15-21% of body weight in obesity trials. Rapid or significant weight loss from any cause can affect bone metabolism, as discussed in the next section. Additionally, gastrointestinal side effects occur in many tirzepatide users, with rates varying by dose: nausea (12-33%), vomiting (5-12%), and diarrhea (9-23%), potentially affecting nutritional intake including calcium and vitamin D, which are essential for bone health.

The American Diabetes Association and American Association of Clinical Endocrinology have not issued specific guidance regarding bone health monitoring for patients on tirzepatide. Clinical judgment should guide individualized assessment, particularly for patients with pre-existing osteoporosis risk factors. Ongoing post-marketing surveillance and longer-term studies will provide more definitive answers about tirzepatide's effects on skeletal health over extended treatment periods.

Weight loss, regardless of the method, can influence bone density through multiple physiological mechanisms. Understanding these pathways helps contextualize concerns about tirzepatide and similar medications. Mechanical loading is a primary stimulus for bone formation—the skeleton adapts to the forces placed upon it. When body weight decreases substantially, the mechanical load on weight-bearing bones diminishes, potentially reducing the stimulus for bone remodeling and maintenance. Studies of bariatric surgery consistently show bone density decreases of 2-10% in the first year post-procedure, with hip and spine most affected.

Nutritional factors play an equally important role. Rapid weight loss can create relative deficiencies in calcium, vitamin D, and protein—all essential for bone health. Tirzepatide's mechanism of action includes delayed gastric emptying and reduced appetite, which may lead to decreased overall nutrient intake. Patients experiencing persistent nausea or early satiety may inadvertently consume insufficient calcium-rich foods or protein. During weight loss, ensuring adequate vitamin D status through appropriate intake and supplementation is important, as serum levels may change with significant changes in body composition.

Hormonal changes accompanying weight loss also affect bone metabolism. Adipose tissue produces estrogen through aromatization of androgens, and substantial fat loss reduces this endogenous estrogen production, potentially affecting bone density, particularly in postmenopausal women. Weight loss also typically decreases leptin levels, a hormone that influences bone formation. Severe caloric restriction may affect stress hormone levels, though this varies considerably between individuals and weight loss approaches.

For GLP-1 and dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonists specifically, preclinical research suggests these incretin hormones may have direct effects on bone cells. GLP-1 receptors are expressed on osteoblasts (bone-forming cells), and some animal studies suggest GLP-1 may actually support bone formation. However, translating these findings to clinical outcomes in humans remains uncertain. The net effect of tirzepatide on bone health likely represents a balance between potential direct skeletal effects of incretin signaling and the mechanical and nutritional challenges of significant weight loss.

Patients with type 2 diabetes face a complex and somewhat paradoxical relationship with bone health. Despite often having normal or elevated bone mineral density on DXA scanning, individuals with type 2 diabetes experience approximately 40-70% higher fracture risk compared to those without diabetes. This disconnect between bone quantity and bone quality reflects diabetes-related alterations in bone microarchitecture, collagen cross-linking, and bone turnover that are not captured by standard BMD measurements.

Several diabetes-specific factors contribute to skeletal fragility. Chronic hyperglycemia leads to accumulation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) in bone collagen, reducing bone material properties and increasing brittleness. Microvascular complications affecting bone blood supply may impair bone remodeling. Additionally, diabetes-related complications such as neuropathy increase fall risk, compounding fracture susceptibility. Longer diabetes duration is associated with increased fracture risk in observational studies.

Traditional osteoporosis risk factors remain highly relevant in the diabetes population and should be systematically assessed:

Major risk factors include:

Age over 65 years (women) or 70 years (men)

Previous fragility fracture

Family history of hip fracture

Postmenopausal status in women

Low body weight (BMI <20 kg/m²) or recent significant weight loss

Current smoking

Excessive alcohol consumption (>3 drinks daily)

Prolonged corticosteroid use (>3 months at ≥5 mg prednisone equivalent daily)

Chronic kidney disease (common in diabetes)

Vitamin D deficiency

Sedentary lifestyle

Certain diabetes medications also influence bone health. Thiazolidinediones (pioglitazone, rosiglitazone) are associated with increased fracture risk and bone loss. Conversely, metformin may have neutral or slightly protective effects on bone. Insulin use has shown variable associations with fracture risk in different studies. When initiating tirzepatide, clinicians should review the patient's complete medication profile and cumulative risk factor burden to determine whether baseline bone density assessment is warranted.

Importantly, the Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) tends to underestimate fracture risk in patients with type 2 diabetes. Clinicians may compensate by considering diabetes as equivalent to rheumatoid arthritis in the FRAX calculation, adjusting T-scores downward, or using lower intervention thresholds for patients with diabetes.

Patients taking tirzepatide can take proactive steps to support bone health during treatment. A comprehensive approach addresses nutrition, physical activity, and appropriate medical monitoring. These strategies are particularly important for individuals with pre-existing osteoporosis risk factors or those experiencing rapid weight loss.

Nutritional optimization is foundational. Ensure adequate calcium intake of 1,000-1,200 mg daily through dietary sources (dairy products, fortified plant milks, leafy greens, sardines with bones) or supplementation if needed. Vitamin D sufficiency is equally critical—aim for serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels of at least 20-30 ng/mL (depending on clinical guidelines), which typically requires 1,000-2,000 IU daily supplementation, though individual needs vary. Protein intake should be maintained at 1.0-1.2 g/kg body weight daily to support both muscle and bone health during weight loss, with adjustments for those with chronic kidney disease (consult with your healthcare provider). If tirzepatide-related nausea or early satiety limits food intake, consider protein supplements or smaller, more frequent meals.

Weight-bearing and resistance exercise provides essential mechanical stimulus for bone maintenance. Aim for at least 30 minutes of weight-bearing activity (walking, jogging, dancing, stair climbing) most days of the week. Resistance training 2-3 times weekly helps maintain both muscle mass and bone density during weight loss. Balance exercises reduce fall risk, particularly important for older adults or those with diabetic neuropathy.

Medical monitoring and assessment should be individualized based on risk factors. Discuss with your healthcare provider whether baseline bone density testing (DXA scan) is appropriate before starting tirzepatide, particularly if you are a woman over 65, a man over 70, postmenopausal with risk factors, have a history of fractures, or have multiple risk factors. In the US, treatment is typically recommended for those with a T-score of ≤-2.5, a history of hip or vertebral fracture, or a FRAX 10-year probability of ≥3% for hip fracture or ≥20% for major osteoporotic fracture.

When to seek medical attention: Contact your healthcare provider if you experience unexplained bone pain, height loss, or fractures while taking tirzepatide. Report persistent gastrointestinal symptoms that limit nutritional intake. If you have established osteoporosis, ensure appropriate treatment (bisphosphonates, denosumab, or other bone-specific therapies) is optimized before and during tirzepatide therapy. Regular follow-up allows monitoring of weight loss velocity and adjustment of bone health strategies as needed. While tirzepatide is not known to cause osteoporosis, maintaining skeletal health during significant metabolic change requires attention and proactive management.

No, clinical trials and FDA labeling have not identified a direct causal link between tirzepatide and osteoporosis. However, the substantial weight loss it produces may indirectly affect bone metabolism through reduced mechanical loading and potential nutritional changes.

Bone density testing should be individualized based on your risk factors. Discuss with your healthcare provider if you are over 65 (women) or 70 (men), postmenopausal with risk factors, have a fracture history, or have multiple osteoporosis risk factors.

Maintain adequate calcium (1,000-1,200 mg daily) and vitamin D intake, consume sufficient protein (1.0-1.2 g/kg body weight), perform regular weight-bearing and resistance exercise, and discuss appropriate monitoring with your healthcare provider based on your individual risk factors.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.