LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

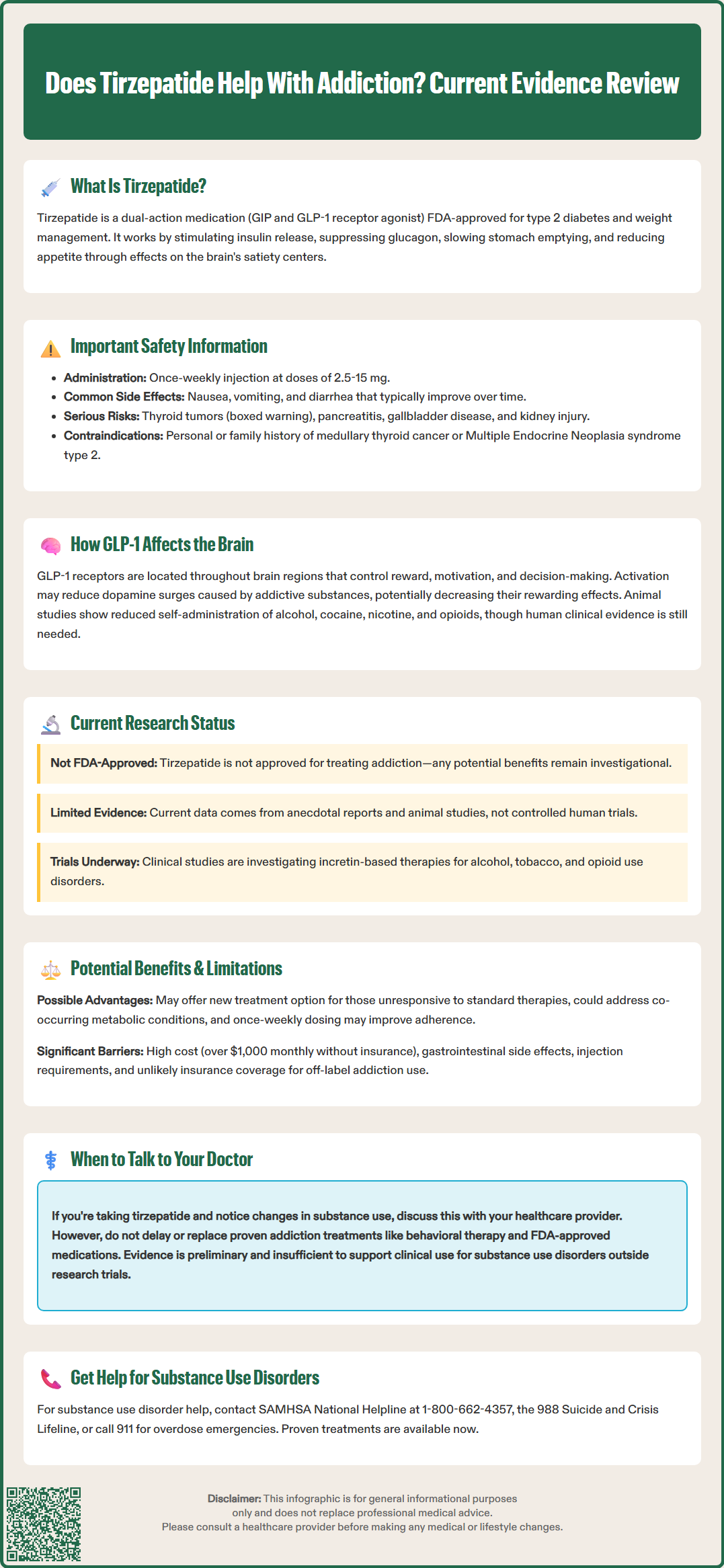

Tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Zepbound) is an FDA-approved medication for type 2 diabetes and chronic weight management that works by activating both GIP and GLP-1 receptors. Recent observations have sparked interest in whether tirzepatide might influence addictive behaviors beyond food intake, as these receptors affect brain reward pathways. While preliminary research on GLP-1 receptor agonists suggests potential effects on substance use, evidence specific to tirzepatide and addiction remains limited. Currently, there is no FDA-approved indication for tirzepatide in treating substance use disorders, and any potential benefits require validation through rigorous clinical trials before clinical application.

Quick Answer: Tirzepatide's effects on addiction are not established, with no FDA approval for substance use disorders and only preliminary evidence suggesting potential benefits.

Tirzepatide is a novel glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist approved by the FDA for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus (under the brand name Mounjaro) and chronic weight management in adults (as Zepbound). This dual-action medication represents a significant advancement in metabolic disease management, offering enhanced glycemic control and substantial weight loss compared to single-receptor agonists.

The mechanism of action involves simultaneous activation of both GIP and GLP-1 receptors, which are incretin hormones naturally produced in the gastrointestinal tract. When tirzepatide binds to GLP-1 receptors, it stimulates glucose-dependent insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells, suppresses inappropriate glucagon release, and slows gastric emptying. The GIP receptor activation complements these effects by further enhancing insulin secretion and may contribute to improved lipid metabolism.

Beyond its metabolic effects, tirzepatide significantly reduces appetite and food intake through both peripheral and central mechanisms. The medication has effects on hypothalamic regions involved in satiety and reward processing, though direct blood-brain barrier penetration in humans remains uncertain. This central mechanism has prompted researchers to investigate whether tirzepatide might influence other reward-driven behaviors, including substance use and addiction.

Tirzepatide is administered as a once-weekly subcutaneous injection, with doses ranging from 2.5 mg to 15 mg depending on the indication and individual response. Common adverse effects include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation, which are typically mild to moderate and diminish over time with dose titration. Important safety considerations include a boxed warning for thyroid C-cell tumors, contraindications in patients with personal/family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma or Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia syndrome type 2, and risks of pancreatitis, gallbladder disease, hypoglycemia (when used with insulin or insulin secretagogues), and acute kidney injury. Tirzepatide may reduce the effectiveness of oral contraceptives, requiring alternative or backup contraception methods.

Research examining tirzepatide's potential effects on addiction is in its early stages, with most evidence derived from preclinical studies, case reports, and observational data rather than randomized controlled trials. There is currently no FDA-approved indication for tirzepatide in treating substance use disorders, and clinicians should recognize that any discussion of addiction-related benefits remains investigational.

Observational reports have noted changes in alcohol consumption among some patients prescribed tirzepatide for diabetes or obesity. These anecdotal observations have generated interest in the scientific community, prompting researchers to explore whether the medication's effects on brain reward pathways might extend beyond food intake to other addictive substances. However, these observations are preliminary and have not been validated in controlled studies specific to tirzepatide.

Preliminary animal studies suggest that GLP-1 receptor agonists may modulate dopaminergic signaling in brain regions associated with reward and motivation, including the nucleus accumbens and ventral tegmental area. These findings have led to ongoing clinical trials investigating GLP-1-based therapies for alcohol use disorder and other substance use conditions. It is important to emphasize that tirzepatide-specific research in addiction remains limited compared to other GLP-1 receptor agonists like semaglutide and exenatide, which have more published data in this area.

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) and other research organizations are currently funding studies to systematically evaluate whether incretin-based medications, including tirzepatide, can effectively reduce substance use behaviors. Several trials can be found on ClinicalTrials.gov investigating GLP-1 receptor agonists for various substance use disorders. Until these rigorous trials are completed, any potential benefits for addiction should be considered preliminary and require further validation through well-designed clinical research.

GLP-1 receptors are widely distributed throughout the central nervous system, including regions critically involved in reward processing, motivation, and decision-making. These receptors are found in the hypothalamus, hippocampus, amygdala, and in areas associated with the mesolimbic reward pathway. This anatomical distribution provides a biological basis for understanding how GLP-1 receptor agonists might influence behaviors beyond glucose metabolism and appetite regulation.

The mesolimbic dopamine system, often called the brain's reward circuit, plays a central role in addiction pathology. Addictive substances typically increase dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens, creating pleasurable sensations that reinforce drug-seeking behavior. Preclinical research indicates that GLP-1 receptor activation may attenuate this dopamine surge in response to drugs of abuse, potentially reducing their rewarding effects. Animal studies have demonstrated that GLP-1 receptor agonists can decrease self-administration of alcohol, cocaine, nicotine, and opioids in rodent models, though these findings require translation to human clinical outcomes.

Neuroimaging studies in humans have shown that GLP-1 receptor agonists alter brain activity in response to food cues, reducing activation in reward-related regions. Researchers hypothesize that similar mechanisms might apply to drug and alcohol cues, potentially diminishing craving intensity and the motivation to use substances, though direct evidence for this in humans with substance use disorders remains limited. Additionally, GLP-1 signaling appears to influence stress response systems and emotional regulation, which are important factors in addiction vulnerability and relapse.

It is important to note that while the GLP-1 component of tirzepatide likely contributes to these neurobiological effects, the additional GIP receptor activation introduces complexity. The specific contribution of GIP signaling to reward processing and addictive behaviors remains less well understood, and the combined effects of dual agonism may differ from single GLP-1 receptor activation. Further research is needed to fully characterize tirzepatide's unique neurobiological profile and its potential implications for addiction treatment.

The potential benefits of tirzepatide for substance use disorders, if confirmed through rigorous research, could represent a valuable addition to existing treatment approaches. Current evidence-based treatments for addiction include behavioral therapies, mutual support groups, and FDA-approved medications such as naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram for alcohol use disorder; buprenorphine, methadone, and extended-release naltrexone for opioid use disorder; and varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine replacement therapies for tobacco use disorder. If tirzepatide proves effective, it might offer an alternative or complementary approach, particularly for individuals who have not responded adequately to standard treatments or who have co-occurring metabolic conditions.

One theoretical advantage is that tirzepatide addresses multiple physiological systems simultaneously. Many individuals with substance use disorders also struggle with obesity, metabolic syndrome, or type 2 diabetes—conditions for which tirzepatide is already approved. A medication that could potentially improve both metabolic health and reduce substance use would address the complex, interconnected nature of these conditions. Additionally, the once-weekly dosing schedule may improve adherence compared to daily medications, though this requires confirmation in addiction populations.

However, significant limitations and uncertainties must be acknowledged. First, there is currently insufficient evidence from randomized controlled trials to support tirzepatide's use for addiction treatment. The existing data consists primarily of case reports and observational studies, which cannot establish causation or rule out confounding factors. Second, the medication's adverse effect profile—particularly gastrointestinal symptoms, as well as risks of pancreatitis, gallbladder disease, and hypoglycemia when combined with certain medications—may limit tolerability in some patients, potentially affecting treatment retention.

Cost and accessibility represent additional barriers. Tirzepatide is expensive, with monthly costs exceeding $1,000 without insurance coverage, and insurance authorization for off-label addiction treatment would likely be challenging. Furthermore, the medication requires subcutaneous injection, which may present challenges for some patients. Patient selection, monitoring protocols, and integration with comprehensive addiction treatment programs would require careful consideration. While off-label prescribing is legal in the US, tirzepatide is generally not recommended for addiction treatment outside of clinical trials or specialist oversight until stronger evidence emerges.

The current evidence regarding tirzepatide's effects on addiction is preliminary and does not support routine clinical use for substance use disorders at this time. While emerging data suggest a potential signal worthy of further investigation, there is no established causal relationship between tirzepatide treatment and reduced addictive behaviors. Clinicians and patients should interpret early reports with appropriate caution and recognize the distinction between hypothesis-generating observations and proven therapeutic interventions.

Most available evidence comes from the broader class of GLP-1 receptor agonists rather than tirzepatide specifically. Studies of semaglutide, liraglutide, and exenatide have shown promising results in reducing alcohol consumption in both animal models and small human trials. Recent pharmacoepidemiological studies published in journals such as JAMA Network Open have found that individuals prescribed GLP-1 receptor agonists for diabetes had lower rates of alcohol-related events compared to those on other diabetes medications, suggesting a potential association. However, these findings require replication, and the specific contribution of tirzepatide's dual GIP/GLP-1 mechanism remains unclear.

Several ongoing clinical trials are investigating incretin-based therapies for alcohol use disorder, tobacco use disorder, and opioid use disorder. These studies will provide more definitive answers about efficacy, optimal dosing, patient selection criteria, and safety considerations. Until results from these rigorous trials become available, any use of tirzepatide for addiction should be considered experimental and generally not recommended outside of clinical trials or specialist oversight.

For patients currently taking tirzepatide for approved indications who notice changes in their substance use patterns, open communication with healthcare providers is essential. These observations should be documented and may contribute to our understanding of the medication's effects. However, patients with active substance use disorders require comprehensive, evidence-based addiction treatment that may include behavioral therapy, peer support, and FDA-approved medications for their specific condition. Tirzepatide should not replace or delay access to these established interventions.

Individuals seeking help for substance use disorders can contact the SAMHSA National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357) or the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline for support and treatment referrals. For medical emergencies related to substance use, including overdose, call 911 immediately.

No, tirzepatide is not FDA-approved for treating substance use disorders or addiction. It is currently approved only for type 2 diabetes mellitus (Mounjaro) and chronic weight management (Zepbound), and any potential addiction-related benefits remain investigational.

Current evidence is preliminary and consists mainly of observational reports, case studies, and animal research rather than randomized controlled trials. Most data comes from other GLP-1 receptor agonists, not tirzepatide specifically, and cannot establish causation or support clinical use for addiction at this time.

Individuals with substance use disorders should pursue evidence-based treatments including behavioral therapy, peer support, and FDA-approved medications for their specific condition. Tirzepatide should not replace established addiction treatments and is generally not recommended for substance use disorders outside of clinical trials or specialist oversight.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.