LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

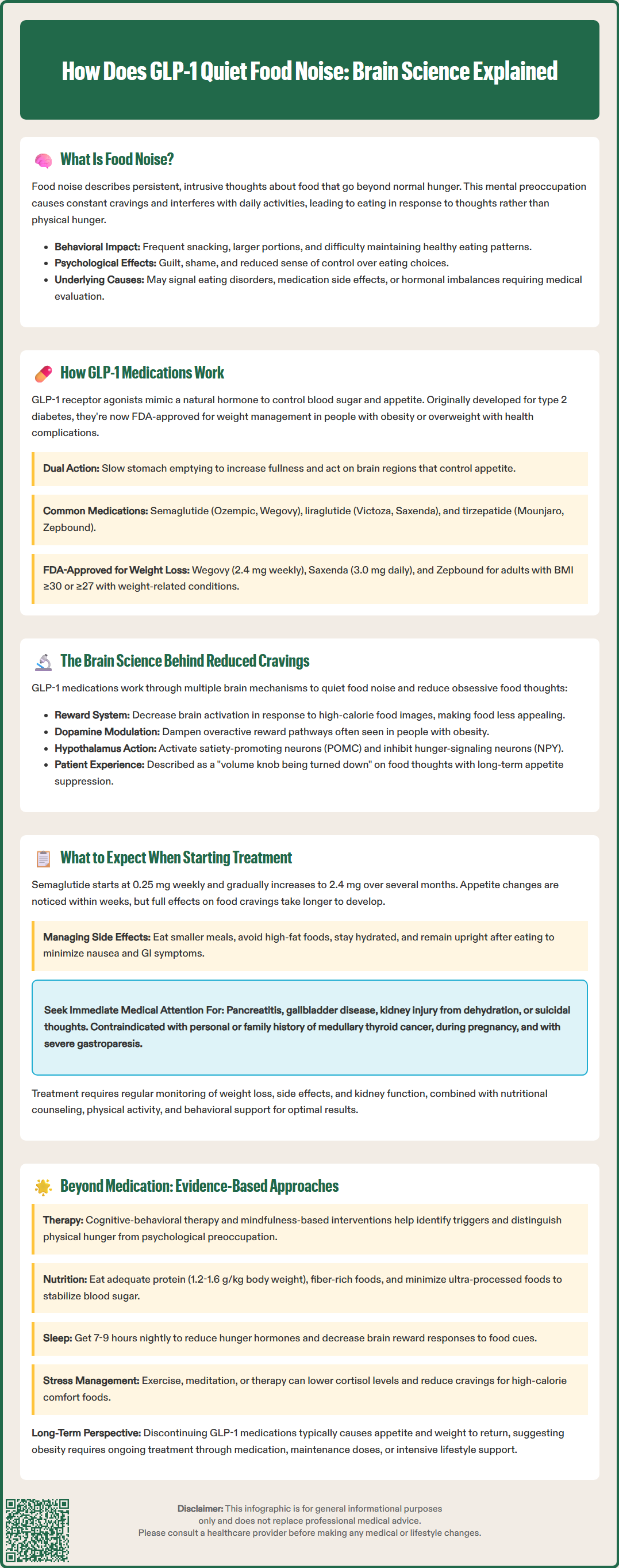

Many individuals struggle with persistent, intrusive thoughts about food throughout the day—a phenomenon increasingly described as "food noise." This constant mental preoccupation with eating can interfere with daily activities, contribute to excess caloric intake, and make weight management feel like an exhausting mental battle. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, a class of medications originally developed for type 2 diabetes, have emerged as effective tools for reducing this cognitive burden. By acting on brain regions that regulate appetite and reward processing, these medications appear to quiet food-related thoughts, diminish cravings, and help patients regain control over their eating behaviors.

Quick Answer: GLP-1 medications quiet food noise by activating receptors in brain regions that regulate appetite and reward processing, reducing neural responses to food cues and diminishing the mental preoccupation with eating.

We offer compounded medications and Zepbound®. Compounded medications are prepared by licensed pharmacies and are not FDA-approved. References to Wegovy®, Ozempic®, Rybelsus®, Mounjaro®, or Saxenda®, or other GLP-1 brands, are informational only. Compounded and FDA-approved medications are not interchangeable.

Food noise refers to the persistent, intrusive thoughts about food that occupy mental space throughout the day. These thoughts may manifest as constant cravings, preoccupation with the next meal, mental planning around food availability, or difficulty concentrating on other tasks due to food-related rumination. While not a formal medical diagnosis or clinically defined term, the concept has gained recognition among healthcare providers and patients as a meaningful descriptor of the cognitive burden associated with appetite dysregulation.

Individuals experiencing significant food noise often report that eating becomes a primary focus of their day, even shortly after consuming a meal. This phenomenon differs from normal hunger cues or occasional cravings. The intrusive nature of these thoughts can interfere with work productivity, social interactions, and overall quality of life. Many patients describe feeling controlled by food rather than making autonomous choices about eating.

The impact on eating behavior is substantial. Food noise frequently contributes to frequent snacking, larger portion sizes, and difficulty adhering to structured eating patterns. Individuals may find themselves eating in response to these mental cues rather than physiological hunger, leading to excess caloric intake and weight gain over time. The psychological distress associated with constant food preoccupation can also contribute to feelings of guilt, shame, and reduced self-efficacy regarding dietary management.

It's important to note that persistent, distressing food-related thoughts may sometimes indicate an underlying eating disorder such as binge eating disorder or bulimia nervosa, which require specialized assessment and treatment. Additionally, certain medications (including some antipsychotics, antidepressants, and corticosteroids) and endocrine conditions can contribute to increased appetite and food preoccupation. Individuals experiencing significant distress from food-related thoughts should discuss these symptoms with their healthcare provider for appropriate evaluation.

While some evidence suggests that intrusive food thoughts may be more common in individuals with obesity, the relationship is complex and bidirectional. Neurobiological factors, including altered reward pathway signaling and hormonal dysregulation, appear to play significant roles in the intensity and persistence of food-related thoughts. Understanding this phenomenon has become increasingly important as clinicians recognize that weight management involves not only behavioral modification but also addressing underlying neurochemical factors that influence appetite regulation.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists represent a class of medications originally developed for type 2 diabetes management, with some now FDA-approved for chronic weight management. These agents mimic the action of endogenous GLP-1, an incretin hormone naturally secreted by intestinal L-cells in response to food intake. The physiological role of native GLP-1 includes stimulating insulin secretion, suppressing glucagon release, and slowing gastric emptying—all mechanisms that contribute to glucose homeostasis.

GLP-1 receptors are distributed throughout multiple organ systems, including the pancreas, gastrointestinal tract, cardiovascular system, and importantly, the central nervous system. In the brain, GLP-1 receptors are found in regions integral to appetite regulation, including the hypothalamus, brainstem, and reward-processing areas such as the nucleus accumbens and ventral tegmental area. This widespread receptor distribution explains the multifaceted effects of GLP-1 medications beyond glycemic control.

Currently available incretin-based therapies include GLP-1 receptor agonists such as semaglutide (Ozempic for diabetes; Wegovy for weight management), liraglutide (Victoza for diabetes; Saxenda for weight management), dulaglutide (Trulicity, approved for diabetes only), and oral semaglutide (Rybelsus, approved for diabetes only). Tirzepatide (Mounjaro for diabetes; Zepbound for weight management) represents a distinct class as a dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist. Most of these medications are administered via subcutaneous injection, with dosing frequencies ranging from daily to weekly depending on the specific agent, though oral semaglutide is available as a daily tablet.

For weight management specifically, the FDA has approved semaglutide 2.4 mg weekly (Wegovy), liraglutide 3.0 mg daily (Saxenda), and tirzepatide (Zepbound) for adults with BMI ≥30 kg/m² or ≥27 kg/m² with at least one weight-related comorbidity. Wegovy and Saxenda also have adolescent indications with specific criteria.

The mechanism by which these medications reduce appetite involves both peripheral and central pathways. Peripherally, these agents slow gastric emptying, which prolongs satiety after meals and reduces the rate at which nutrients enter the small intestine. Centrally, these medications may affect brain appetite centers through multiple pathways, including signaling via vagal afferents and action on circumventricular organs (brain regions with a more permeable blood-brain barrier). The extent of direct blood-brain barrier penetration varies by agent. This coordinated physiological response reduces hunger, increases fullness, and notably, appears to diminish the cognitive preoccupation with food that characterizes food noise.

The ability of GLP-1 receptor agonists to reduce food cravings and quiet food noise appears to stem from their effects on brain reward circuitry. Neuroimaging studies using functional MRI have investigated how these medications alter neural responses to food cues. For example, research by van Bloemendaal et al. (2014) and ten Kulve et al. (2016) has shown that when patients receive GLP-1 therapy, there may be reduced activation in brain regions associated with reward processing and motivation when viewing high-calorie food images compared to baseline or placebo conditions.

These brain regions are central to the dopaminergic reward system, which governs motivation, pleasure, and reinforcement learning related to food intake. In individuals with obesity, this reward system often shows heightened responsiveness to food cues, contributing to increased cravings and difficulty resisting palatable foods. Animal studies suggest that GLP-1 receptor activation may modulate dopamine signaling in these pathways, potentially dampening the reward value assigned to food stimuli. While human evidence for direct dopamine modulation is more limited, the clinical effect translates into patients reporting that food seems less appealing, cravings diminish, and the mental space occupied by food-related thoughts decreases substantially.

Additionally, GLP-1 receptors in the hypothalamus interact with key appetite-regulating neuropeptides, including pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) and neuropeptide Y (NPY). Activation of POMC neurons promotes satiety, while inhibition of NPY neurons reduces hunger signaling. Through these mechanisms, GLP-1 medications create a neurohormonal environment that favors reduced food intake and decreased appetite drive.

Patient-reported outcomes from clinical trials consistently demonstrate significant reductions in food cravings and preoccupation with eating. In the STEP trials evaluating semaglutide for weight management, participants reported marked improvements in control over eating and reductions in food cravings compared to placebo, as measured by validated instruments such as the Control of Eating Questionnaire. Similar findings have been reported in the SURMOUNT trials with tirzepatide. Many patients describe the experience as a "volume knob being turned down" on food thoughts—a qualitative shift that facilitates adherence to reduced-calorie eating patterns without the constant mental struggle previously experienced.

It's worth noting that early in treatment, nausea and other gastrointestinal side effects may contribute to reduced food appeal, though the appetite-suppressing effects persist even as these side effects typically diminish with continued therapy. While individual responses vary, the majority of patients on therapeutic doses report meaningful changes in their relationship with food and eating behavior.

Initiation of GLP-1 therapy follows a gradual dose-escalation protocol designed to minimize gastrointestinal adverse effects while achieving therapeutic benefit. For semaglutide (Wegovy), the typical starting dose is 0.25 mg weekly, with increases every four weeks until reaching the maintenance dose of 2.4 mg weekly (or 1.7 mg if the higher dose is not tolerated). This titration schedule allows the body to adapt to the medication's effects on gastric emptying and reduces the incidence of nausea and vomiting, the most commonly reported side effects.

Patients often notice changes in appetite and food-related thoughts within the first few weeks of treatment, though the full effect on food noise may take several weeks to months as doses are increased. Early in treatment, the most prominent sensation is typically increased fullness after meals and reduced capacity to consume large portions. As therapy continues and doses escalate, many patients report a more profound shift—the intrusive thoughts about food begin to quiet, cravings diminish, and eating becomes a more neutral, less emotionally charged activity.

Common adverse effects include nausea (reported in 20-44% of patients), vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, and abdominal discomfort. These gastrointestinal symptoms are generally most pronounced during dose escalation and tend to improve with continued use. Strategies to minimize side effects include eating smaller, more frequent meals, avoiding high-fat foods, staying well-hydrated, and not lying down immediately after eating. If symptoms are severe or persistent, dose escalation may be delayed or the dose reduced temporarily.

Serious adverse effects require vigilance and prompt medical attention. FDA-labeled warnings include:

Risk of thyroid C-cell tumors (contraindicated in patients with personal/family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma or Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia syndrome type 2)

Pancreatitis (report severe abdominal pain, with or without vomiting)

Gallbladder disease (including gallstones and cholecystitis)

Acute kidney injury secondary to dehydration from gastrointestinal symptoms

Hypoglycemia when used with insulin or insulin secretagogues (dose adjustments may be needed)

Diabetic retinopathy complications in patients with type 2 diabetes and pre-existing retinopathy

Suicidal behavior and ideation (monitor for depression or suicidal thoughts)

Intestinal obstruction/ileus (particularly with severe constipation)

These medications are contraindicated during pregnancy and should be discontinued at least two months before a planned pregnancy. They should be used with caution in patients with severe gastroparesis or other severe gastrointestinal diseases.

Regular monitoring during GLP-1 therapy should include assessment of weight loss progress, tolerability, adherence, and screening for adverse effects. Laboratory monitoring may include renal function tests, particularly in patients experiencing significant gastrointestinal symptoms. The American Diabetes Association recommends that weight management with GLP-1 agonists be part of a comprehensive approach including nutritional counseling, physical activity, and behavioral support to optimize outcomes and maintain weight loss long-term.

While GLP-1 medications represent a powerful pharmacological tool for reducing food noise, comprehensive management often benefits from a multimodal approach. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) specifically adapted for eating behaviors can help patients develop awareness of food-related thought patterns, identify triggers for intrusive food thoughts, and implement cognitive restructuring techniques. Mindfulness-based interventions have shown promise in reducing food cravings and improving eating awareness, helping individuals distinguish between physiological hunger and psychological food preoccupation.

Nutritional strategies that support stable blood glucose levels may also help minimize food noise. Diets emphasizing adequate protein intake, fiber-rich foods, and balanced macronutrient distribution can promote sustained satiety and reduce the frequency of hunger-driven food thoughts. Protein needs should be individualized, with general targets of 1.2-1.6 g/kg body weight for many adults, though lower amounts may be appropriate for those with chronic kidney disease or other conditions requiring protein modification. Consultation with a registered dietitian is recommended for personalized nutrition guidance.

Research by Hall et al. (2019) suggests that minimizing ultra-processed foods, which are engineered to be hyperpalatable and may dysregulate appetite signaling, can reduce food preoccupation over time and lead to spontaneous reduction in calorie intake.

Sleep optimization represents another evidence-based intervention for managing food noise. Sleep deprivation is associated with increased activation of reward-processing brain regions in response to food cues and elevated levels of ghrelin, the hunger hormone. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommends 7-9 hours of quality sleep per night for adults. Addressing sleep disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea, which is common in individuals with obesity, may independently improve appetite regulation.

Stress management techniques warrant consideration, as chronic stress activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and can increase cortisol levels, which may intensify food cravings, particularly for high-calorie comfort foods. Evidence-based stress reduction approaches include regular physical activity, meditation, progressive muscle relaxation, and when appropriate, psychotherapy for underlying anxiety or mood disorders.

For patients who achieve significant reduction in food noise with GLP-1 therapy, questions about long-term management arise. Data from the STEP 4 trial demonstrated that discontinuation of semaglutide typically results in return of appetite and substantial weight regain, indicating that for many individuals, ongoing treatment may be necessary to maintain benefits. This has led to conceptualization of obesity as a chronic disease requiring long-term management rather than a condition amenable to short-term intervention.

Clinicians should engage patients in shared decision-making regarding treatment duration, considering individual response, tolerability, cost, and patient preferences. Some patients may successfully transition to lower maintenance doses, while others may benefit from combining pharmacotherapy with intensive lifestyle interventions. For those who cannot continue GLP-1 therapy, other FDA-approved anti-obesity medications may be considered. Referral to registered dietitians, behavioral health specialists, or comprehensive weight management programs can provide additional support for sustained behavior change and weight maintenance, whether patients continue medication or attempt discontinuation with close monitoring.

Most patients notice changes in appetite and food-related thoughts within the first few weeks of treatment, though the full effect on food noise typically develops over several weeks to months as doses are gradually increased to therapeutic levels.

Clinical trial data shows that discontinuation of GLP-1 therapy typically results in return of appetite, food preoccupation, and weight regain, indicating that ongoing treatment may be necessary to maintain the reduction in food noise for many individuals.

While GLP-1 medications are highly effective, other evidence-based approaches include cognitive-behavioral therapy, mindfulness interventions, optimizing sleep quality, stress management, and dietary strategies that emphasize protein, fiber, and minimally processed foods.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.