LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

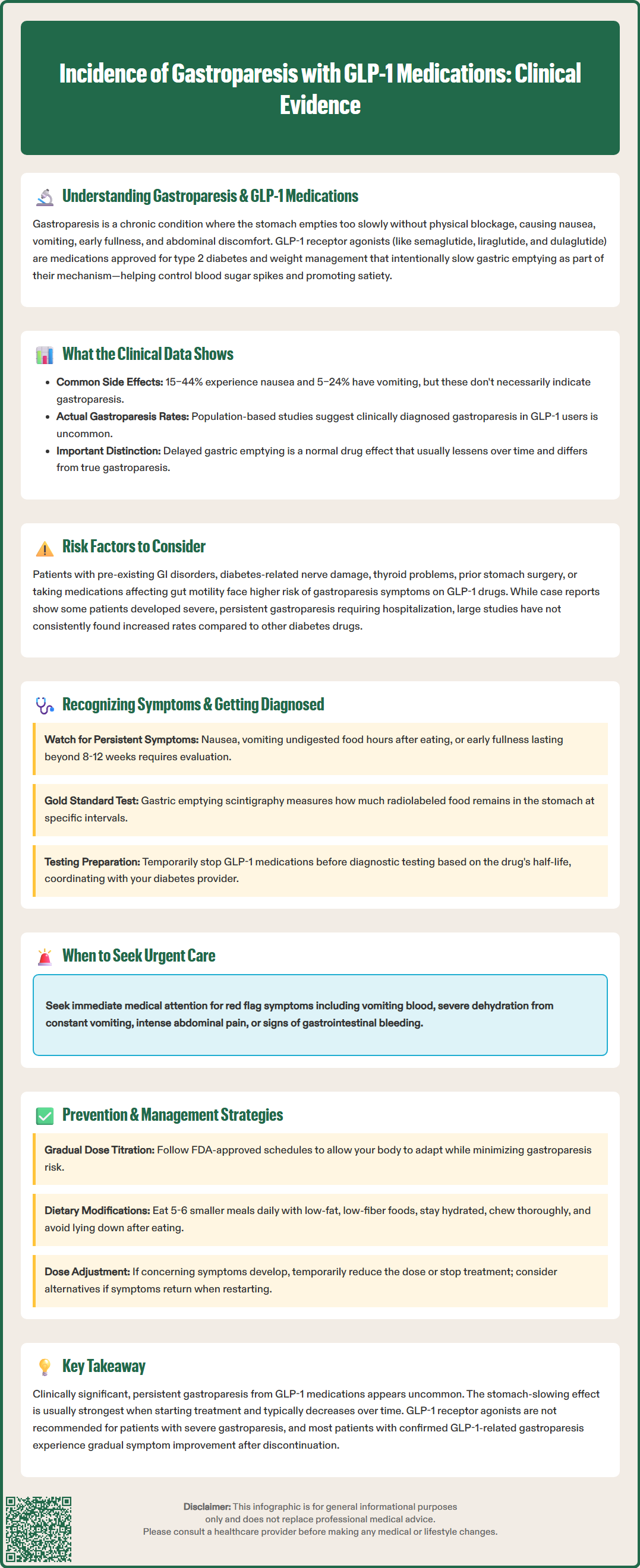

Incidence of gastroparesis with GLP-1 medications remains a topic of clinical concern as these agents gain widespread use for type 2 diabetes and weight management. GLP-1 receptor agonists like semaglutide and liraglutide intentionally slow gastric emptying as part of their therapeutic mechanism, but distinguishing this expected effect from true gastroparesis presents diagnostic challenges. While clinical trials report gastrointestinal symptoms in 15–44% of users, formally diagnosed gastroparesis appears uncommon. Recent pharmacovigilance data and population studies continue to refine our understanding of this potential complication. This article examines current evidence on gastroparesis incidence, risk factors, diagnostic approaches, and management strategies for patients using GLP-1 medications.

Quick Answer: Clinically diagnosed gastroparesis in GLP-1 receptor agonist users appears uncommon, though precise incidence rates remain uncertain due to methodologic challenges in distinguishing expected gastric emptying delay from pathologic gastroparesis.

We offer compounded medications and Zepbound®. Compounded medications are prepared by licensed pharmacies and are not FDA-approved. References to Wegovy®, Ozempic®, Rybelsus®, Mounjaro®, or Saxenda®, or other GLP-1 brands, are informational only. Compounded and FDA-approved medications are not interchangeable.

Gastroparesis is a chronic disorder characterized by delayed gastric emptying in the absence of mechanical obstruction. The condition results from impaired coordination of gastric motility, preventing the stomach from emptying its contents at a normal rate. Common symptoms include nausea, vomiting, early satiety, postprandial fullness, and abdominal discomfort. Gastroparesis can significantly impact nutritional status and quality of life, with diabetes mellitus being the most common identifiable cause in the United States.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists are a class of medications approved for type 2 diabetes management and, more recently, for chronic weight management. These agents include semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy), dulaglutide (Trulicity), liraglutide (Victoza, Saxenda), and others. Tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Zepbound) is a dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and GLP-1 receptor agonist, not a pure GLP-1 receptor agonist. These medications work through multiple mechanisms: they enhance glucose-dependent insulin secretion, suppress inappropriate glucagon release, and reduce appetite through central nervous system pathways.

Critically, GLP-1 receptor agonists slow gastric emptying as part of their therapeutic mechanism. This physiologic effect helps regulate postprandial glucose excursions and contributes to satiety and weight loss. The gastric emptying delay is typically dose-dependent and most pronounced during initial therapy. While this slowing often attenuates over time with continued treatment, the effect may persist with long-acting agents and varies between individuals. FDA labeling notes that delayed gastric emptying may affect absorption of oral medications and that these agents are not recommended for patients with severe gastroparesis. The distinction between expected pharmacologic gastric slowing and pathologic gastroparesis requires careful evaluation of both incidence data and clinical presentation.

Determining the true incidence of gastroparesis associated with GLP-1 receptor agonist use presents significant methodologic challenges. Clinical trial data from FDA-approved labeling typically report gastrointestinal adverse effects broadly, with nausea occurring in 15–44% of patients depending on the specific agent and dose, while vomiting affects 5–24% of users. However, these symptoms do not necessarily indicate gastroparesis, and formal gastroparesis diagnoses are rarely reported as distinct endpoints in registration trials.

Recent pharmacovigilance studies have attempted to quantify this association. A 2023 analysis of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) identified increased reporting of gastroparesis among GLP-1 users compared to other diabetes medications. However, it's important to note that FAERS data cannot establish incidence rates or causality due to voluntary reporting, potential reporting bias, and lack of denominator data. The system serves primarily as a signal detection tool.

Population-based studies suggest that clinically diagnosed gastroparesis in GLP-1 users appears uncommon, though precise incidence estimates vary by study methodology, population characteristics, and diagnostic criteria. Large US claims database analyses continue to refine our understanding of both absolute and relative risk compared to other diabetes therapies.

It is essential to distinguish between gastric emptying delay—an expected pharmacologic effect that typically attenuates with continued therapy—and true gastroparesis, which implies persistent, clinically significant gastric dysfunction. Most patients experience some degree of delayed emptying during GLP-1 initiation, but this does not constitute gastroparesis unless symptoms are severe, persistent, and confirmed by objective testing. The American Diabetes Association Standards of Care advises caution when using these agents in patients with gastroparesis. Current evidence suggests that if GLP-1-associated gastroparesis occurs, it remains an uncommon complication, though ongoing surveillance continues to refine our understanding of this potential risk.

Several patient characteristics may increase susceptibility to gastroparesis symptoms during GLP-1 therapy. Pre-existing gastrointestinal disorders, particularly functional dyspepsia or irritable bowel syndrome, appear to predispose patients to more pronounced GI symptoms. Patients with longstanding diabetes and established autonomic neuropathy face elevated baseline gastroparesis risk independent of GLP-1 use, making causality attribution particularly challenging in this population. Poor glycemic control, hypothyroidism, prior gastric or bariatric surgery, and concurrent use of medications that affect gastric motility (such as opioids, anticholinergics, or cannabis) may also amplify risk. Rapid dose escalation and higher maintenance doses are additional considerations.

The clinical evidence linking GLP-1 medications to persistent gastroparesis remains evolving and somewhat controversial. Mechanistic studies confirm that GLP-1 receptor activation in the gastric fundus and pylorus reduces gastric motility and delays emptying. While this effect often attenuates over time, it may persist to varying degrees with long-acting agents. Case reports and case series have documented instances of severe, persistent gastroparesis temporally associated with GLP-1 initiation, with some patients requiring hospitalization for refractory nausea and vomiting. In several reported cases, symptoms improved following medication discontinuation, suggesting a potential causal relationship.

Conversely, large observational studies have not consistently demonstrated increased gastroparesis incidence compared to other diabetes therapies when accounting for confounding factors. A critical consideration is that diabetes itself substantially increases gastroparesis risk—affecting up to 5% of patients with type 1 diabetes and 1% with type 2 diabetes. This makes it difficult to isolate the independent contribution of GLP-1 medications. Current evidence suggests that while GLP-1 agents clearly affect gastric emptying as part of their mechanism, progression to clinically significant, persistent gastroparesis appears uncommon. FDA labeling for these medications notes that delayed gastric emptying may affect the absorption of concomitantly administered oral medications and that they are not recommended for use in patients with severe gastroparesis.

Recognizing gastroparesis in patients taking GLP-1 medications requires careful clinical assessment, as symptoms overlap considerably with common, transient GLP-1 side effects. Cardinal symptoms of gastroparesis include persistent nausea, recurrent vomiting (particularly of undigested food consumed hours earlier), early satiety, postprandial fullness, bloating, and upper abdominal discomfort. Weight loss may occur, though this can be difficult to interpret in patients using GLP-1 agents for weight management. Symptoms that persist beyond the initial 8–12 weeks of therapy, worsen over time, or significantly impair nutritional intake warrant further evaluation.

Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for gastroparesis when patients report vomiting undigested food many hours after meals, severe refractory nausea despite antiemetic therapy, or inability to maintain adequate oral intake. Red flags requiring urgent evaluation include hematemesis, intractable vomiting leading to dehydration, severe abdominal pain or distention, and signs of gastrointestinal bleeding. Physical examination may reveal a succussion splash, though this finding has limited sensitivity. Laboratory evaluation should assess for metabolic derangements, including electrolyte abnormalities, dehydration, and malnutrition markers. Importantly, clinicians must exclude mechanical obstruction and other organic pathology before attributing symptoms to gastroparesis.

Diagnostic confirmation requires objective demonstration of delayed gastric emptying. Gastric emptying scintigraphy remains the gold standard, measuring the retention of a radiolabeled solid meal at standardized intervals (typically 0, 1, 2, and 4 hours post-ingestion) following the American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society/Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging protocol. Gastroparesis is diagnosed when gastric retention exceeds 60% at 2 hours or 10% at 4 hours. Alternative diagnostic modalities include wireless motility capsule testing and gastric emptying breath tests, though these are less widely available. Upper endoscopy, while not diagnostic for gastroparesis, helps exclude structural abnormalities and may reveal retained food in the fasting state.

Patients should temporarily discontinue GLP-1 medications before gastric emptying studies according to facility-specific protocols, which typically consider the half-life of the specific agent. This medication hold should be coordinated with the patient's diabetes care provider to prevent hyperglycemia or ketosis during the testing period. Other medications that affect gastric motility (opioids, anticholinergics, prokinetics) should also be held per protocol.

Proactive risk mitigation strategies can minimize gastroparesis-related complications in patients prescribed GLP-1 receptor agonists. Gradual dose titration represents the most important preventive measure, allowing physiologic adaptation to gastric emptying effects. FDA-approved labeling provides specific escalation schedules that should be followed carefully, with consideration for even slower titration in high-risk patients. Clinicians should educate patients about expected gastrointestinal effects during initiation, emphasizing that mild nausea and fullness typically improve within 4–8 weeks.

Dietary modifications can substantially improve tolerability and reduce gastroparesis risk. Patients should be counseled to:

Consume smaller, more frequent meals (5–6 per day) rather than large portions

Emphasize low-fat, low-fiber foods that empty more readily from the stomach

Ensure adequate hydration, particularly with liquid calories if solid food tolerance is poor

Avoid lying down immediately after meals

Chew food thoroughly and eat slowly

For patients developing concerning symptoms, temporary dose reduction or treatment interruption may be necessary. If symptoms resolve with discontinuation and recur with rechallenge, alternative diabetes or weight management therapies should be considered. Antiemetic medications, including ondansetron, may provide symptomatic relief. Metoclopramide, an FDA-approved prokinetic for gastroparesis, carries a boxed warning for tardive dyskinesia and should generally be limited to 12 weeks or less of therapy. Other prokinetic options include low-dose erythromycin for short-term use, and domperidone, which is available in the US only through an FDA Investigational New Drug application.

Patients with diabetes should coordinate with their diabetes care provider to adjust insulin or secretagogue doses during periods of poor oral intake to reduce hypoglycemia risk. Referral to gastroenterology is appropriate when patients experience persistent symptoms despite conservative management, require objective gastroparesis diagnosis, or need specialized nutritional support. Patients with severe symptoms, inability to maintain hydration, or significant weight loss may require hospitalization for intravenous fluids, nutritional support, and symptom management.

In cases of confirmed, severe gastroparesis attributable to GLP-1 therapy, medication discontinuation is generally recommended, consistent with FDA labeling that these agents are not recommended for patients with severe gastroparesis. Most patients experience gradual symptom improvement over weeks to months after discontinuation. Ongoing research continues to refine our understanding of this potential complication, and clinicians should remain vigilant for emerging safety data while balancing the substantial metabolic benefits these medications provide for appropriate patients.

Clinically diagnosed gastroparesis in GLP-1 users appears uncommon, though precise incidence rates are difficult to establish. While 15–44% of patients experience gastrointestinal symptoms like nausea, these typically represent expected pharmacologic effects rather than true gastroparesis, which requires objective confirmation through gastric emptying studies.

Normal GLP-1 side effects include mild nausea and fullness that typically improve within 4–8 weeks, while gastroparesis involves persistent symptoms beyond 12 weeks, vomiting of undigested food hours after meals, and severe impairment of nutritional intake requiring objective diagnosis via gastric emptying scintigraphy.

FDA labeling states that GLP-1 receptor agonists are not recommended for patients with severe gastroparesis. If confirmed severe gastroparesis is attributed to GLP-1 therapy, medication discontinuation is generally recommended, with most patients experiencing gradual symptom improvement over weeks to months.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.