LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

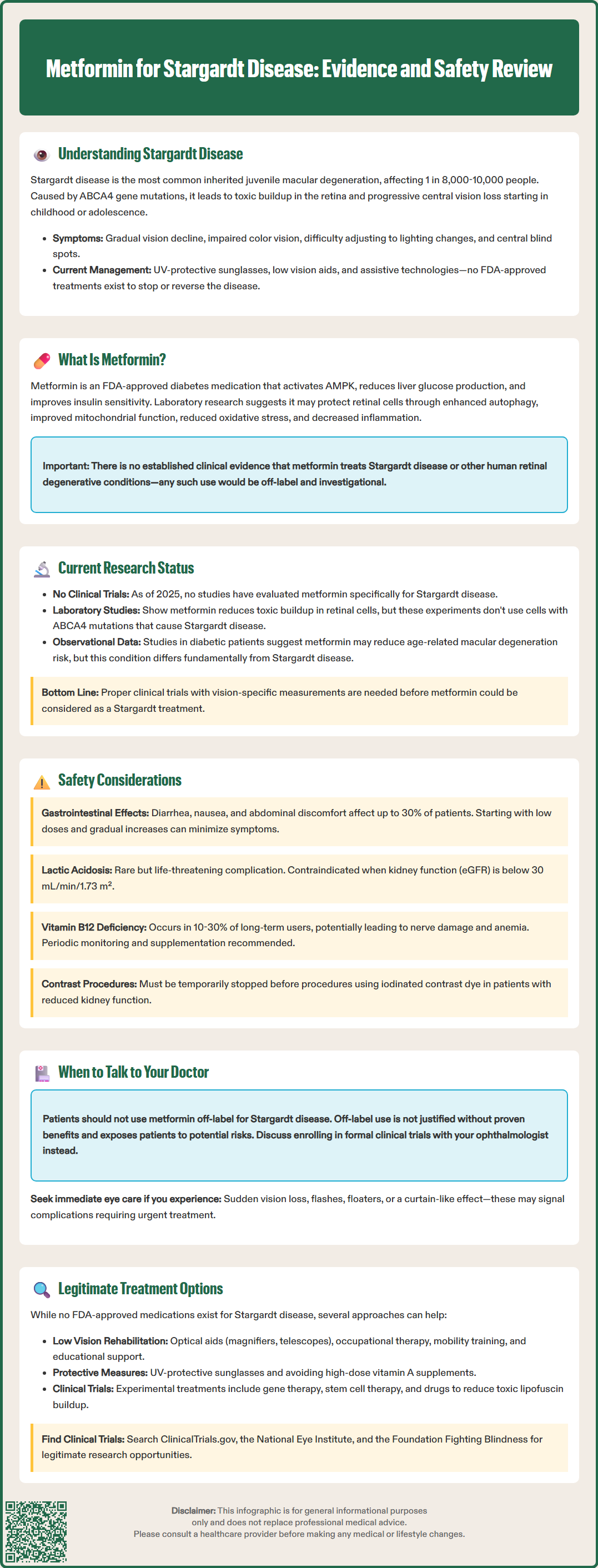

Metformin for Stargardt disease represents an investigational concept without established clinical evidence. Stargardt disease, the most common inherited juvenile macular degeneration, currently has no FDA-approved treatments to halt its progression. While metformin—a diabetes medication—has demonstrated theoretical neuroprotective properties in laboratory studies, no clinical trials have evaluated its efficacy for Stargardt disease. This article examines the scientific rationale behind metformin's potential retinal effects, reviews the absence of clinical evidence, discusses safety considerations, and outlines current standard-of-care approaches for managing this inherited retinal dystrophy.

Quick Answer: Metformin is not an FDA-approved or evidence-based treatment for Stargardt disease, with no clinical trials supporting its use for this inherited retinal dystrophy.

Stargardt disease is the most common form of inherited juvenile macular degeneration, affecting approximately 1 in 8,000 to 10,000 individuals. This autosomal recessive condition typically manifests in childhood or adolescence, causing progressive central vision loss due to mutations in the ABCA4 gene. These mutations lead to accumulation of lipofuscin—a toxic byproduct—in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), resulting in photoreceptor death and characteristic yellow-white flecks visible on fundoscopic examination.

Patients with Stargardt disease experience gradual decline in visual acuity, impaired color vision, and difficulty adapting to changes in lighting. Central scotomas develop as macular degeneration progresses, while peripheral vision typically remains intact until advanced stages. Diagnosis involves comprehensive ophthalmologic evaluation including fundus autofluorescence imaging and optical coherence tomography, with electroretinography and genetic testing for ABCA4 mutations used based on clinical context.

Currently, there are no FDA-approved treatments that halt or reverse Stargardt disease progression. Management focuses on supportive care and visual rehabilitation. Patients are generally advised to wear UV-protective sunglasses as a precautionary measure, as some evidence suggests light exposure may contribute to disease progression. Low vision aids, occupational therapy, and assistive technologies help maximize remaining vision. High-dose vitamin A supplementation should be avoided, as it may potentially worsen lipofuscin accumulation, though patients should discuss multivitamin contents with their clinician.

Several investigational therapies are under development, including gene therapy approaches targeting ABCA4 mutations, stem cell transplantation to replace damaged RPE cells, and pharmacologic agents aimed at reducing lipofuscin accumulation. Clinical trials are ongoing, but no treatments have yet demonstrated sufficient efficacy and safety for regulatory approval. This unmet medical need has prompted exploration of repurposed medications, including metformin, for potential neuroprotective effects in retinal degenerative diseases.

Patients experiencing sudden vision loss, flashes, floaters, or a curtain-like effect over vision should seek urgent ophthalmologic evaluation, as these may indicate complications requiring immediate attention.

Metformin is a biguanide antihyperglycemic agent primarily prescribed for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Its principal mechanism involves activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), a cellular energy sensor that regulates glucose and lipid metabolism. Metformin primarily reduces hepatic glucose production, while also enhancing peripheral insulin sensitivity and potentially decreasing intestinal glucose absorption. The FDA-approved labeling indicates metformin for glycemic control in adults and children aged 10 years and older with type 2 diabetes.

Beyond its antidiabetic effects, metformin has demonstrated pleiotropic properties that have generated interest in ophthalmology and neurodegenerative disease research. AMPK activation influences multiple cellular pathways relevant to retinal health, including autophagy enhancement, mitochondrial function optimization, and reduction of oxidative stress. These mechanisms theoretically could protect photoreceptors and RPE cells from degenerative processes.

Preclinical studies have suggested metformin may exert neuroprotective effects in various retinal disease models. AMPK activation promotes clearance of damaged cellular components through autophagy, potentially reducing toxic accumulations like lipofuscin. Additionally, metformin's anti-inflammatory properties and ability to modulate cellular metabolism have been hypothesized to slow photoreceptor degeneration. Some laboratory research indicates metformin may reduce oxidative damage in retinal cells and improve mitochondrial efficiency.

However, it is critical to emphasize that these theoretical benefits are derived primarily from laboratory studies and animal models. The translation of these findings to human retinal degenerative diseases, particularly Stargardt disease, remains highly speculative. There is no established clinical evidence supporting metformin as a treatment for Stargardt disease, and its use for this indication would be considered off-label and investigational. The biological plausibility requires rigorous clinical validation before any therapeutic recommendations can be made.

As of 2025, there are no published clinical trial evidence or registered studies specifically evaluating metformin as a treatment for Stargardt disease. The existing research landscape consists primarily of preclinical investigations exploring metformin's effects on retinal degeneration models and observational studies examining retinal outcomes in diabetic patients taking metformin. These studies provide limited and indirect insights into metformin's potential role in inherited retinal dystrophies.

Some laboratory research has investigated AMPK activators, including metformin, in cellular models of retinal degeneration. These studies have demonstrated that AMPK activation can enhance autophagy and reduce accumulation of toxic metabolites in RPE cells. However, these experiments typically use non-specific retinal degeneration models rather than cells with ABCA4 mutations characteristic of Stargardt disease. The relevance of these findings to the specific pathophysiology of Stargardt disease remains uncertain.

Observational studies in diabetic populations have yielded mixed results regarding metformin's effects on various retinal conditions. Some epidemiologic data suggest metformin users may have reduced risk of age-related macular degeneration compared to users of other antidiabetic medications, though these findings are confounded by multiple variables including glycemic control, diabetes duration, and concurrent medications. Importantly, age-related macular degeneration and Stargardt disease have distinct pathophysiologic mechanisms, limiting the applicability of such observations.

The absence of clinical trial data specific to Stargardt disease represents a significant knowledge gap. Any potential therapeutic application would require properly designed clinical studies with appropriate endpoints, including visual acuity measurements, fundus autofluorescence changes, and optical coherence tomography assessments. Until such evidence emerges, metformin cannot be recommended for Stargardt disease management. Patients interested in investigational approaches should discuss participation in formal clinical trials with their ophthalmologist rather than pursuing off-label metformin use.

Metformin has an established safety profile when used for its FDA-approved indication of type 2 diabetes mellitus, though several important adverse effects and contraindications require consideration, including a Boxed Warning for lactic acidosis. The most common side effects are gastrointestinal, affecting up to 30% of patients and including diarrhea, nausea, abdominal discomfort, and metallic taste. These symptoms typically occur during treatment initiation and often resolve with continued use or dose reduction. Starting with low doses and gradual titration can minimize gastrointestinal intolerance.

The most serious potential adverse effect is lactic acidosis, a rare but life-threatening complication occurring in approximately 0.03 cases per 1,000 patient-years. Risk factors include renal impairment, hepatic dysfunction, acute illness, hypoxic states, and excessive alcohol intake. The FDA labeling contraindicates metformin in patients with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) below 30 mL/min/1.73 m² and recommends not initiating metformin when eGFR is between 30-45 mL/min/1.73 m². Dose reduction applies only to ongoing therapy in patients whose eGFR falls into this range.

Metformin should be temporarily discontinued before procedures involving iodinated contrast agents in patients with eGFR 30-60 mL/min/1.73 m², liver disease, alcoholism, heart failure, or when receiving intra-arterial contrast. Renal function should be reassessed 48 hours after the procedure before restarting metformin. Unlike many diabetes medications, metformin rarely causes hypoglycemia when used as monotherapy.

Long-term metformin use is associated with vitamin B12 deficiency in approximately 10-30% of patients, potentially causing peripheral neuropathy and anemia. The American Diabetes Association recommends periodic monitoring of vitamin B12 levels, particularly in patients with anemia or peripheral neuropathy. Supplementation should be considered when deficiency is documented.

For individuals without diabetes considering off-label metformin use for any condition, including Stargardt disease, the risk-benefit calculation differs substantially from its use in diabetes management. Without proven efficacy for retinal protection, exposing patients to potential adverse effects cannot be justified. Additionally, metformin requires regular monitoring including renal function assessment and periodic laboratory evaluation. Patients should not initiate metformin for Stargardt disease outside of supervised clinical trial settings, and any off-label use should involve careful discussion with both ophthalmology and primary care providers regarding monitoring requirements and potential risks.

As of 2025, there are no FDA-approved pharmacologic treatments specifically for Stargardt disease. This represents a significant unmet medical need for affected patients and their families. The absence of approved therapies reflects the complexity of treating inherited retinal degenerations and the challenges of developing interventions that can effectively halt or reverse photoreceptor loss. Current standard of care remains supportive, focusing on maximizing functional vision and preventing further damage.

Patients with Stargardt disease should receive comprehensive low vision rehabilitation services. This includes prescription of appropriate optical aids such as magnifiers, telescopic devices, and electronic video magnification systems. Occupational therapy can teach adaptive strategies for daily activities, while orientation and mobility training helps maintain independence. Educational accommodations and vocational rehabilitation services are particularly important for pediatric and young adult patients. Genetic counseling provides valuable information regarding inheritance patterns and family planning considerations.

Several investigational approaches are under active development in clinical trials. Gene therapy strategies aim to deliver functional ABCA4 genes to retinal cells using viral vectors, potentially correcting the underlying genetic defect. Multiple gene therapy candidates are in early-phase clinical trials, though challenges include achieving adequate retinal transduction and managing immune responses. Stem cell therapies seek to replace damaged RPE cells with healthy cells derived from induced pluripotent stem cells or embryonic stem cells. Pharmacologic approaches under investigation include compounds designed to reduce lipofuscin accumulation, such as ALK-001 (deuterated vitamin A), which has shown preliminary results in early clinical trials, and RBP4 antagonists like tinlarebant.

Patients interested in emerging therapies should discuss clinical trial participation with their ophthalmologist. Resources such as ClinicalTrials.gov, the National Eye Institute (NEI), and the Foundation Fighting Blindness provide information about ongoing studies. It is essential that patients avoid unproven treatments marketed outside of legitimate clinical research, as these may be ineffective, costly, and potentially harmful. Regular ophthalmologic monitoring remains important for tracking disease progression and identifying patients who may benefit from future approved therapies. Referral to specialized retinal centers with expertise in inherited retinal diseases ensures access to the most current management strategies and clinical trial opportunities.

No, metformin is not an FDA-approved treatment for Stargardt disease, and no clinical trials have demonstrated its efficacy for this inherited retinal dystrophy. Its use for Stargardt disease would be off-label and investigational without supporting evidence.

As of 2025, there are no FDA-approved pharmacologic treatments for Stargardt disease. Current management focuses on supportive care including low vision rehabilitation, UV-protective eyewear, and participation in clinical trials for investigational gene therapies and pharmacologic agents.

Metformin carries risks including gastrointestinal side effects in up to 30% of patients, rare but serious lactic acidosis (particularly with renal impairment), vitamin B12 deficiency with long-term use, and requires regular renal function monitoring. Off-label use without proven benefit cannot be justified given these potential adverse effects.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.