LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

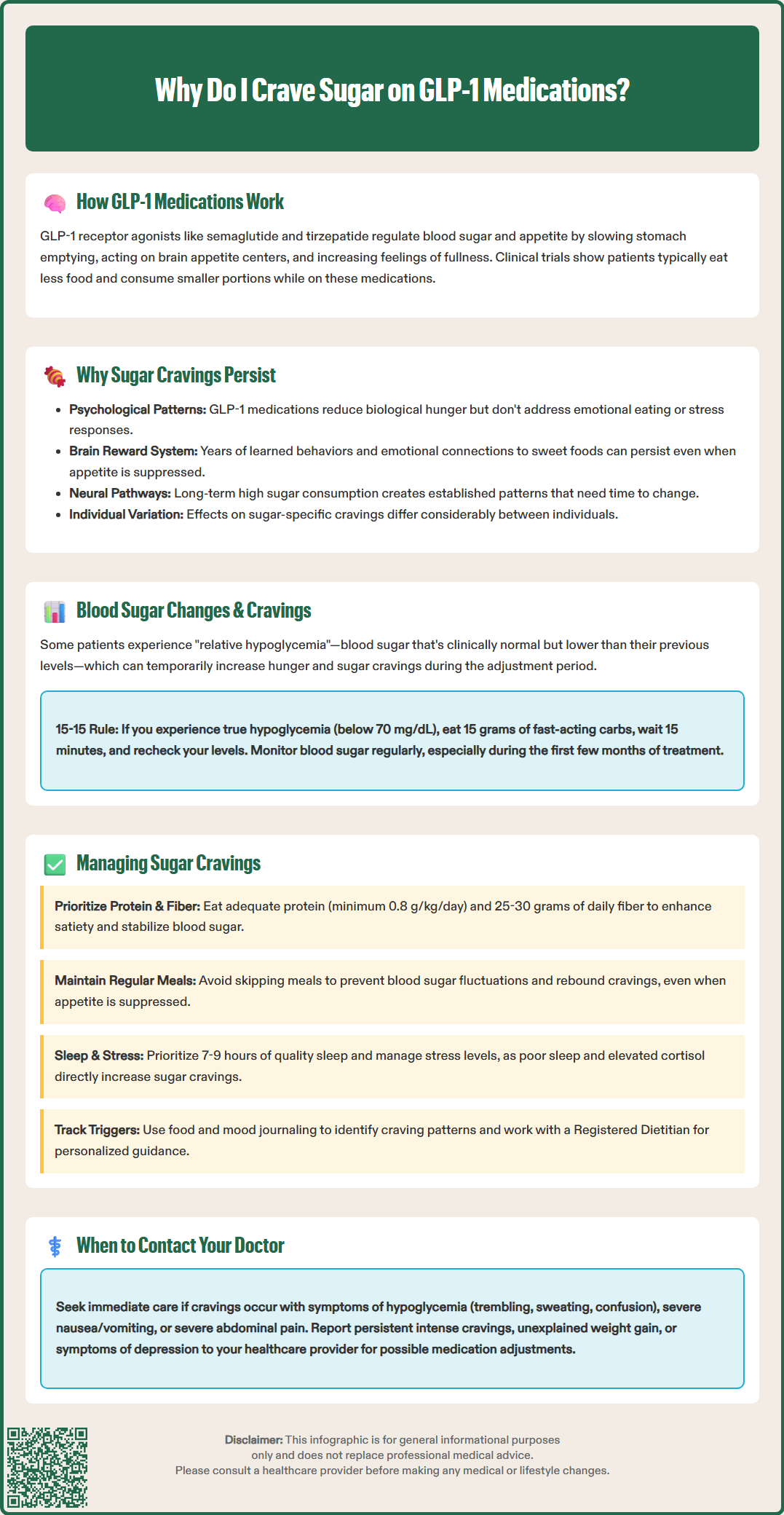

Many patients starting GLP-1 medications like semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy) or tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Zepbound) expect their appetite and food cravings to disappear completely. While these medications effectively reduce hunger for most people, some continue experiencing sugar cravings despite treatment. This phenomenon can be confusing and frustrating, but it doesn't mean the medication isn't working. Understanding why sugar cravings persist involves examining how GLP-1 medications affect brain reward pathways, blood sugar regulation, psychological eating patterns, and individual metabolic responses. This article explores the science behind persistent sugar cravings during GLP-1 treatment and provides evidence-based strategies for managing them effectively.

Quick Answer: Sugar cravings may persist on GLP-1 medications because these drugs primarily address biological hunger mechanisms but don't directly target psychological eating patterns, learned behaviors, or individual variations in brain reward pathways.

We offer compounded medications and Zepbound®. Compounded medications are prepared by licensed pharmacies and are not FDA-approved. References to Wegovy®, Ozempic®, Rybelsus®, Mounjaro®, or Saxenda®, or other GLP-1 brands, are informational only. Compounded and FDA-approved medications are not interchangeable.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, including semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy), and tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Zepbound), which is a dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist, influence blood sugar regulation and appetite. These medications are typically administered as weekly injections with doses that increase gradually over time.

These medications work through several mechanisms, including slowing gastric emptying (though this effect may attenuate over time), acting on appetite centers in the hypothalamus, and enhancing feelings of fullness. According to FDA labeling, the precise mechanism for weight loss is not fully understood. Clinical trials such as the STEP program (semaglutide) and SURMOUNT trials (tirzepatide) demonstrate that patients typically experience reduced caloric intake, with many reporting decreased interest in food and smaller portion sizes.

Emerging research suggests these medications may influence food preferences and cravings. Some studies indicate they might affect reward pathways in the brain, potentially altering the pleasure associated with eating certain foods. However, evidence regarding specific effects on sugar versus fat cravings is still developing, and individual responses vary considerably. The impact on specific food cravings is not uniform across all patients.

Understanding this variability helps set realistic expectations for patients beginning treatment with these medications.

Despite the appetite-suppressing effects of GLP-1 medications, some patients continue to experience sugar cravings, which can be confusing and frustrating. Several factors may explain this phenomenon, and it is important to recognize that persistent sugar cravings do not indicate treatment failure.

First, sugar cravings often have psychological and behavioral components that extend beyond physiological hunger. Emotional eating patterns, stress responses, and habitual behaviors developed over years may persist even when appetite signals are reduced. GLP-1 medications primarily address biological hunger and satiety mechanisms but do not directly target learned eating behaviors or emotional connections to food. Patients who historically used sweet foods for comfort, reward, or stress relief may continue to experience psychological cravings independent of physical hunger.

Second, the brain's reward system responds differently to various macronutrients. While preliminary research suggests GLP-1 medications may affect food preferences, their impact on sugar-specific cravings appears more variable. The neurobiological mechanisms involved are complex and still being investigated.

Additionally, interindividual variability in pharmacologic response, baseline eating patterns, and metabolic factors influence treatment response. Patients with a history of significant sugar consumption may have established neural pathways that require more time to recalibrate. The medication dosage, duration of treatment, and concurrent lifestyle modifications also play important roles in determining the extent to which specific cravings diminish. The evidence regarding why some patients experience persistent sugar cravings while others do not continues to evolve, with ongoing research examining these differences.

GLP-1 receptor agonists exert significant effects on glucose metabolism, which can indirectly influence carbohydrate and sugar cravings. These medications enhance glucose-dependent insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells and suppress inappropriate glucagon release, leading to improved glycemic control. For patients with type 2 diabetes, this typically results in lower average blood glucose levels and reduced postprandial glucose excursions.

Importantly, when used alone, GLP-1 medications have a low risk of causing hypoglycemia (low blood sugar). However, this risk increases significantly when combined with insulin or sulfonylureas, which may require dose reductions of these other medications.

Some patients may experience what's sometimes called relative hypoglycemia—blood glucose levels that are normal by clinical standards but lower than the patient's previous baseline. This physiological adjustment period can manifest as increased hunger or specific cravings for quick-energy foods like sugar and refined carbohydrates. These symptoms typically don't require treatment with fast-acting carbohydrates unless blood glucose is actually below 70 mg/dL.

True hypoglycemia—defined as blood glucose below 70 mg/dL—triggers a strong physiological drive to consume carbohydrates. The American Diabetes Association recommends the "15-15 rule" for treating hypoglycemia: consume 15 grams of fast-acting carbohydrates, wait 15 minutes, and recheck blood glucose. Repeat if necessary until glucose is above 70 mg/dL.

Patients should monitor blood glucose levels as recommended by their healthcare provider, particularly during the initial months of therapy or after dose adjustments. The American Diabetes Association recommends individualized glycemic targets, and providers may need to adjust concurrent diabetes medications to prevent hypoglycemia. If sugar cravings coincide with symptoms such as trembling, sweating, confusion, or palpitations, blood glucose should be checked immediately.

Addressing persistent sugar cravings during GLP-1 treatment requires a multifaceted approach that combines nutritional strategies, behavioral modifications, and appropriate medical management. The following evidence-based strategies can help patients navigate this challenge while optimizing treatment outcomes.

Nutritional approaches include:

Balanced protein intake: Consuming adequate protein helps enhance satiety. The USDA Dietary Guidelines recommend 0.8 g/kg/day as a minimum, with individualized goals based on health status. Those with kidney disease should consult their healthcare provider for personalized recommendations.

Focus on fiber: The USDA recommends 25-30 grams of fiber daily for adults, primarily from whole foods like vegetables, fruits, legumes, and whole grains. Adequate fiber helps stabilize blood sugar and promotes fullness.

Regular meal timing: Eating at consistent intervals prevents excessive hunger that can trigger intense sugar cravings. Skipping meals may seem appealing when appetite is suppressed, but it can lead to blood sugar fluctuations and rebound cravings.

Thoughtful carbohydrate choices: Emphasize minimally processed, high-fiber carbohydrate sources. While glycemic index/load concepts may help some individuals, the American Diabetes Association notes that overall dietary patterns matter more than focusing solely on glycemic index.

Adequate hydration: Thirst is sometimes misinterpreted as hunger or cravings. Maintaining proper hydration supports overall metabolic function and may reduce false hunger signals.

Behavioral strategies include identifying triggers for sugar cravings—whether emotional, environmental, or habitual—and developing alternative responses. Mindful eating practices, stress management techniques, and cognitive behavioral approaches can address the psychological components of cravings. Keeping a food and mood journal may help identify patterns and triggers.

Sleep and stress management are often overlooked factors. Poor sleep quality and chronic stress elevate cortisol levels, which can increase sugar cravings and interfere with appetite regulation. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommends 7-9 hours of quality sleep for adults.

Patients should work with Registered Dietitian Nutritionists (RDNs) experienced with obesity/diabetes management and GLP-1 medications to develop personalized nutrition plans that address individual needs, preferences, and metabolic considerations.

While some degree of food cravings during GLP-1 treatment may be normal, certain situations warrant medical evaluation to ensure optimal safety and treatment efficacy.

Seek immediate medical attention if cravings occur alongside:

Symptoms of hypoglycemia (trembling, sweating, confusion, rapid heartbeat, dizziness)

Severe nausea, vomiting, or abdominal pain

Severe upper abdominal pain radiating to the back (possible pancreatitis—stop medication immediately)

Right upper quadrant abdominal pain, fever, or yellowing of skin/eyes (possible gallbladder disease)

Discuss at scheduled follow-up appointments:

Persistent, intense cravings that interfere with daily functioning

Unexplained weight gain or inability to lose weight despite medication adherence

Symptoms of depression, anxiety, or disordered eating patterns

Questions about medication dosage or administration

Healthcare providers can assess whether medication dosage adjustments are appropriate, evaluate for potential hypoglycemia, and screen for underlying conditions that may contribute to cravings, such as insulin resistance or thyroid disorders.

Providers should also review all concurrent medications, as certain drugs (including some antidepressants, antipsychotics, and corticosteroids) can increase appetite and sugar cravings, potentially counteracting GLP-1 effects. Additionally, inadequate dosing or suboptimal medication adherence may result in insufficient appetite suppression.

For patients with diabetes, persistent sugar cravings accompanied by elevated blood glucose readings may indicate inadequate glycemic control requiring treatment intensification. Conversely, cravings with normal or low blood glucose levels may suggest the need to reduce other glucose-lowering medications to prevent hypoglycemia.

A comprehensive evaluation may include laboratory testing (hemoglobin A1c, fasting glucose, thyroid function), review of glucose monitoring data, and assessment of psychological factors. Vitamin B12 levels may be checked, especially for patients also taking metformin. Referral to endocrinology, nutrition specialists, or mental health professionals may be appropriate for complex cases. Open communication with healthcare providers ensures that treatment plans are optimized for individual needs.

No, GLP-1 medications reduce biological hunger and enhance satiety but don't eliminate all cravings, particularly those driven by psychological factors, learned behaviors, or emotional eating patterns. Individual responses vary considerably, and some patients continue experiencing specific food cravings despite effective appetite suppression.

Yes, true hypoglycemia (blood glucose below 70 mg/dL) triggers strong carbohydrate cravings, though GLP-1 medications alone have low hypoglycemia risk. Some patients experience relative hypoglycemia—normal glucose levels that are lower than their previous baseline—which can temporarily increase cravings during the adjustment period.

Seek immediate medical attention if cravings occur with hypoglycemia symptoms (trembling, sweating, confusion), severe abdominal pain, or persistent vomiting. Discuss persistent intense cravings, unexplained weight changes, or symptoms of depression or disordered eating at scheduled follow-up appointments for appropriate evaluation and treatment adjustments.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.