LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

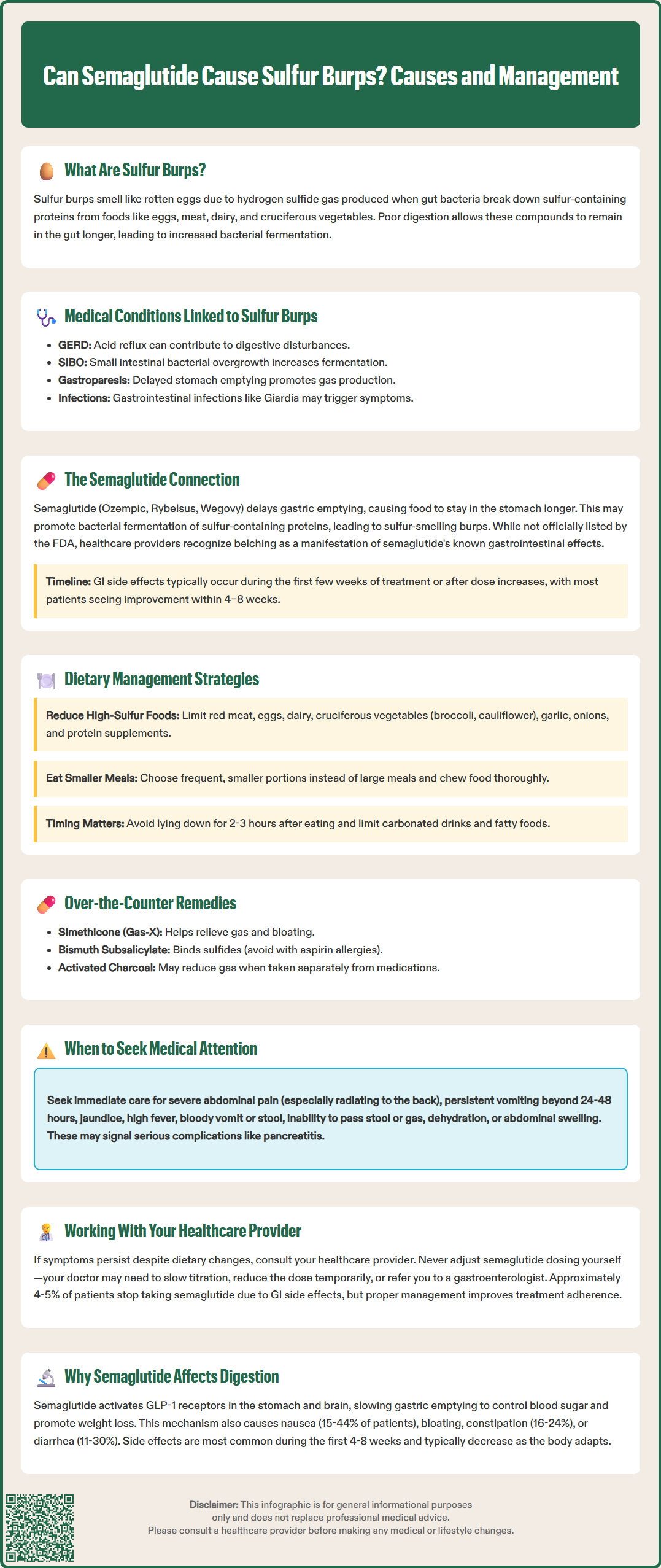

Can semaglutide cause sulfur burps? Many patients taking this GLP-1 medication report experiencing belching with a distinctive rotten egg odor. While sulfur burps aren't specifically listed in FDA prescribing information, semaglutide's mechanism—particularly its effect on delaying gastric emptying—creates conditions that may promote this symptom. Understanding the connection between semaglutide and digestive side effects, including sulfur-odor belching, helps patients manage symptoms effectively while continuing treatment. This article examines the relationship between semaglutide and sulfur burps, explores why they occur, and provides evidence-based strategies for prevention and management.

Quick Answer: Semaglutide may contribute to sulfur burps through its mechanism of delaying gastric emptying, which allows increased bacterial fermentation of sulfur-containing proteins, though this symptom is not specifically listed in FDA labeling.

Sulfur burps are belches that produce a distinctive rotten egg odor caused by hydrogen sulfide gas. This gas forms in the digestive tract when certain bacteria break down sulfur-containing proteins and amino acids from food. While occasional sulfur burps are generally harmless, frequent episodes can indicate underlying digestive disturbances or dietary factors.

Hydrogen sulfide gas can be generated throughout the gastrointestinal tract, particularly in the small intestine and colon where bacterial fermentation is most active. When protein-rich foods containing sulfur compounds—such as eggs, meat, dairy products, cruciferous vegetables, and certain legumes—are not fully digested, gut bacteria ferment these materials and release hydrogen sulfide as a byproduct. Normal digestion typically prevents significant gas accumulation, but when digestive processes are disrupted, sulfur-containing compounds remain in the gastrointestinal tract longer, allowing more bacterial fermentation to occur.

Several conditions may be associated with increased belching, including gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and certain gastrointestinal infections. Conditions specifically linked to sulfurous odor include small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), gastroparesis, and infections such as Giardia lamblia. Dietary factors play a significant role as well—consuming large amounts of sulfur-rich foods, carbonated beverages, or eating too quickly can increase air swallowing and gas production.

For most people, sulfur burps resolve spontaneously within hours to a few days. However, persistent symptoms warrant medical evaluation, particularly if accompanied by severe or worsening abdominal pain, persistent vomiting (>24-48 hours), signs of dehydration, blood in vomit or stool, high fever, unintentional weight loss, or if you're over 60 with new digestive symptoms. Understanding the mechanism behind sulfur burps helps contextualize why certain medications, particularly those affecting gastrointestinal motility, may influence their occurrence.

GLP-1 receptor agonists, including semaglutide, commonly cause gastrointestinal adverse effects, and some patients report belching with a sulfur odor, though "sulfur burps" are not specifically listed in FDA prescribing information. Semaglutide is approved for type 2 diabetes management (Ozempic, Rybelsus) and chronic weight management (Wegovy). The FDA labeling documents gastrointestinal adverse effects broadly—including nausea (occurring in 15–44% of patients depending on dose and indication), vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and constipation.

The potential connection between semaglutide and sulfur-odor belching relates to the medication's mechanism of action. As a GLP-1 agonist, semaglutide delays gastric emptying, meaning food remains in the stomach longer than normal. This delayed transit could create conditions that promote increased bacterial fermentation of sulfur-containing proteins. Clinical studies have documented that GLP-1 receptor agonists slow gastric emptying, particularly during initial therapy and dose titration, though this effect may attenuate somewhat over time.

Gastrointestinal side effects associated with semaglutide typically occur more frequently during the initial weeks of treatment or following dose escalation. Most patients experience improvement as their bodies adjust to the medication over 4–8 weeks, though some individuals may have persistent symptoms requiring intervention.

It is important to note that while there is no official designation of sulfur burps as a distinct adverse effect in regulatory documentation, the gastrointestinal mechanisms affected by semaglutide could plausibly contribute to this patient-reported symptom. Healthcare providers generally recognize belching as a potential manifestation of semaglutide's known gastrointestinal effects rather than an unrelated symptom.

Managing sulfur burps while taking semaglutide requires a multifaceted approach focusing on dietary modifications, eating behaviors, and symptomatic relief strategies. Since delayed gastric emptying is the primary mechanism, interventions that facilitate digestion and reduce sulfur substrate availability can significantly improve symptoms.

Dietary modifications represent the first-line approach. Patients should consider temporarily reducing intake of high-sulfur foods, including:

Red meat, poultry, and eggs

Dairy products (milk, cheese, yogurt)

Cruciferous vegetables (broccoli, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, cabbage)

Allium vegetables (garlic, onions, leeks)

Legumes and certain nuts

Protein supplements, particularly whey-based products

Rather than eliminating these nutritious foods entirely, patients can moderate portions and observe which specific items trigger symptoms. Keeping a food diary helps identify individual patterns.

Eating behavior modifications are equally important. Patients should eat smaller, more frequent meals rather than large portions, as excessive food volume exacerbates delayed gastric emptying. Eating slowly, chewing thoroughly, and avoiding lying down within 2–3 hours after meals can improve digestive efficiency. Limiting carbonated beverages, which introduce additional gas, and reducing fatty foods, which further slow gastric emptying, may provide relief.

Symptomatic management options include over-the-counter remedies such as simethicone (Gas-X), which helps break up gas bubbles, though evidence for hydrogen sulfide specifically is limited. Some patients find relief with bismuth subsalicylate, which can bind sulfide (note: avoid in patients with aspirin allergies or those taking blood thinners). Activated charcoal supplements may absorb intestinal gases, but should be separated from oral medications, including Rybelsus. Ginger may provide mild relief for associated nausea and digestive discomfort, while peppermint should be avoided in patients with GERD as it may worsen symptoms.

Patients should seek urgent medical attention for severe persistent abdominal pain (especially if radiating to the back), persistent vomiting, jaundice, fever, inability to pass stool/gas, or abdominal distension, which could indicate serious complications such as pancreatitis, gallbladder disease, or intestinal obstruction.

For persistent symptoms despite these measures, consult your healthcare provider. Never self-adjust semaglutide dosing; your provider may recommend slowing titration, temporarily reducing the dose, or pausing treatment. Referral to a gastroenterologist is appropriate if symptoms persist beyond 8–12 weeks or significantly impact quality of life.

Understanding why semaglutide causes digestive side effects requires examination of its pharmacological mechanism and the physiological role of GLP-1 in gastrointestinal function. Semaglutide is a long-acting GLP-1 receptor agonist with structural homology to native human GLP-1. While its primary therapeutic effects involve enhancing glucose-dependent insulin secretion and suppressing glucagon release, GLP-1 receptors are widely distributed throughout the gastrointestinal tract, where they exert significant effects on digestive processes.

The most clinically relevant gastrointestinal effect of semaglutide is delayed gastric emptying. GLP-1 receptors in the stomach and pylorus, when activated, slow the rate at which food moves from the stomach into the small intestine. This mechanism contributes to improved glycemic control by reducing postprandial glucose excursions and promotes satiety, supporting weight loss. However, this same effect creates the physiological basis for common adverse effects including nausea, vomiting, early satiety, bloating, and belching. The degree of gastric emptying delay is dose-dependent and most pronounced during treatment initiation and dose escalation.

Semaglutide also affects gastrointestinal motility more broadly. GLP-1 receptors throughout the intestinal tract modulate peristalsis, which can result in either constipation or diarrhea. According to FDA prescribing information, constipation occurs in 16-24% of Wegovy patients and 5-17% of Ozempic patients (dose-dependent), while diarrhea occurs in 11-30% of patients across products and doses.

The central nervous system effects of GLP-1 receptor activation also contribute to gastrointestinal symptoms. GLP-1 receptors in the brainstem area postrema (the brain's "vomiting center") mediate nausea and reduced appetite. This central mechanism works synergistically with peripheral gastrointestinal effects to produce the medication's therapeutic benefits but also its side effect profile.

Clinical trials have consistently demonstrated that gastrointestinal adverse effects are most common during the first 4–8 weeks of therapy and typically diminish as physiological adaptation occurs. The FDA-approved dosing schedules incorporate gradual dose escalation specifically to minimize these effects—starting at 0.25 mg weekly for Ozempic (increasing every 4 weeks), 0.25 mg weekly for Wegovy (increasing every 4 weeks through 2.4 mg), or 3 mg daily for Rybelsus (increasing to 7 mg after 30 days, with optional increase to 14 mg). Despite this approach, approximately 4-5% of patients in clinical trials discontinued semaglutide due to gastrointestinal intolerance. Patient education about expected side effects, their typical time course, and management strategies significantly improves treatment adherence and outcomes.

Sulfur burps associated with semaglutide typically occur most frequently during the first 4–8 weeks of treatment or following dose increases, and usually improve as the body adjusts to the medication. If symptoms persist beyond 8–12 weeks despite dietary modifications, consult your healthcare provider for evaluation and potential management adjustments.

To reduce sulfur burps while taking semaglutide, consider temporarily moderating intake of high-sulfur foods including red meat, eggs, dairy products, cruciferous vegetables (broccoli, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts), garlic, onions, and protein supplements. Rather than complete elimination, reduce portions and identify individual triggers through a food diary.

Do not stop or adjust semaglutide dosing without consulting your healthcare provider. Most gastrointestinal side effects improve with dietary modifications and time as your body adjusts to the medication. Your provider may recommend slowing dose titration, temporarily reducing the dose, or implementing additional management strategies if symptoms are severe or persistent.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.