LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

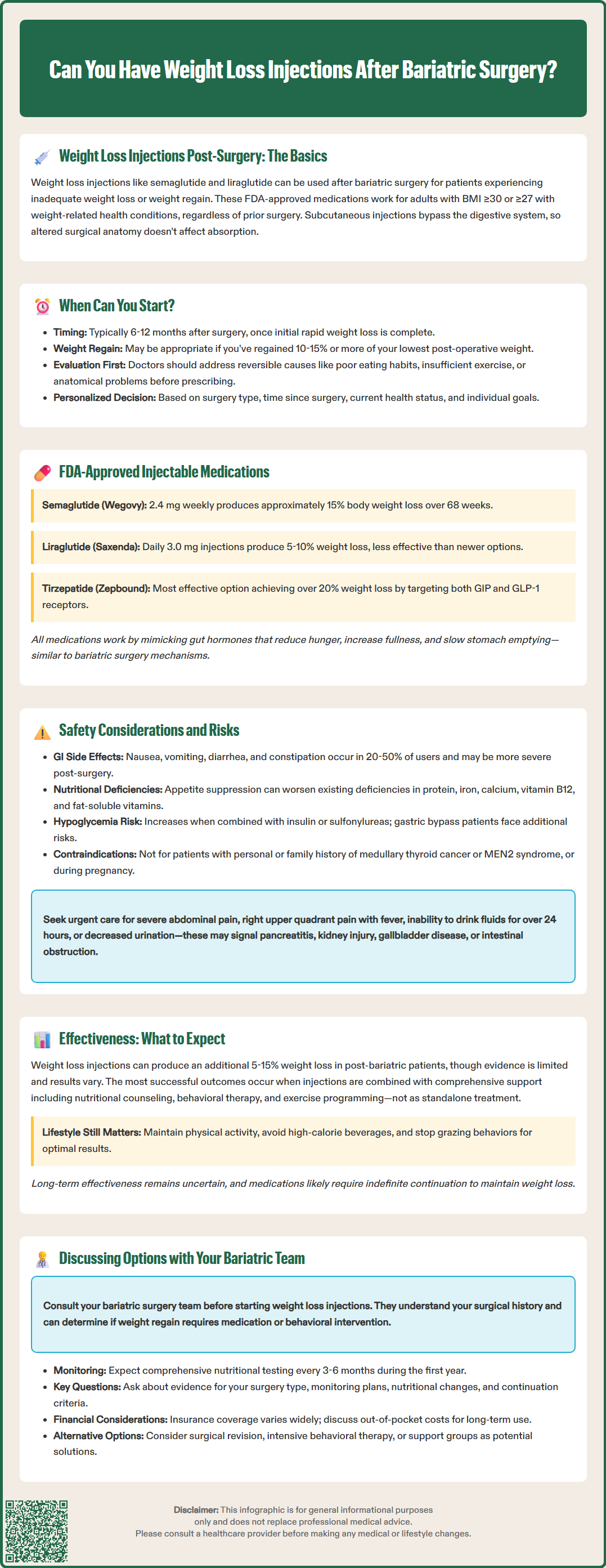

Can you have weight loss injections after bariatric surgery? Yes, injectable weight loss medications can be used following bariatric procedures, though careful medical oversight is essential. Some patients experience inadequate weight loss or weight regain years after surgery, prompting consideration of additional interventions. GLP-1 receptor agonists like semaglutide and liraglutide have emerged as potential adjunctive therapies for post-bariatric patients. These FDA-approved medications work differently than surgery but complement its effects when used appropriately. Understanding when these injections are appropriate, their safety profile in post-surgical patients, and how to integrate them with ongoing bariatric care is crucial for optimal outcomes.

Quick Answer: Weight loss injections can be used after bariatric surgery for patients experiencing inadequate weight loss or weight regain, though timing and patient selection require careful evaluation by the bariatric team.

We offer compounded medications and Zepbound®. Compounded medications are prepared by licensed pharmacies and are not FDA-approved. References to Wegovy®, Ozempic®, Rybelsus®, Mounjaro®, or Saxenda®, or other GLP-1 brands, are informational only. Compounded and FDA-approved medications are not interchangeable.

Bariatric surgery remains one of the most effective interventions for severe obesity, yet some patients experience inadequate weight loss or weight regain years after their procedure. Weight loss injections, particularly glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists such as semaglutide and liraglutide, have emerged as potential adjunctive therapies in this population. These medications can be used after bariatric surgery, though their role requires careful consideration within the context of each patient's surgical history and metabolic status.

The decision to initiate injectable weight loss medications following bariatric surgery should be individualized. These medications are FDA-approved for chronic weight management in adults with a BMI ≥30 kg/m² or ≥27 kg/m² with at least one weight-related comorbidity, regardless of bariatric surgery history. However, clinical trial data specifically examining post-bariatric patients remains limited. Bariatric surgery already produces significant changes in gut hormone secretion, including endogenous GLP-1 elevation, which raises important questions about the incremental benefit of exogenous GLP-1 agonists in this altered physiological state. Importantly, subcutaneous injections bypass the gastrointestinal tract, so absorption is generally unaffected by altered surgical anatomy.

Patients considering weight loss injections after bariatric surgery should understand that these medications are not a substitute for the lifestyle modifications and nutritional protocols essential to long-term surgical success. Rather, they may serve as an additional tool for patients who have reached a weight loss plateau despite adherence to dietary guidelines and physical activity recommendations, or for those experiencing clinically significant weight regain that threatens their metabolic health improvements. A comprehensive evaluation by the bariatric team is essential before initiating any pharmacological weight management strategy in the post-surgical period.

The optimal timing for initiating weight loss injections after bariatric surgery has not been definitively established through randomized controlled trials, and current practice varies among bariatric centers. Many clinicians consider anti-obesity medications after the initial rapid weight loss phase, typically 6-12 months post-operatively, or when patients experience a plateau or weight regain despite adherence to post-surgical recommendations. Earlier initiation may be appropriate in some cases, particularly when significant comorbidities persist.

During the first post-operative months, patients undergo significant metabolic adaptation and typically experience their most dramatic weight loss. Introducing weight loss medications during this period may complicate the assessment of surgical effectiveness and could potentially mask complications such as anastomotic strictures or inadequate nutritional intake. Additionally, the early post-operative period requires close monitoring of protein intake, vitamin and mineral supplementation, and hydration status—factors that could be further complicated by the gastrointestinal side effects commonly associated with GLP-1 receptor agonists.

For patients experiencing weight regain, the timing of intervention depends on several factors including the degree of regain, presence of obesity-related comorbidities, and documentation of adherence to behavioral recommendations. Weight regain of 10-15% or more from the lowest post-operative weight, or failure to achieve adequate excess weight loss, may prompt consideration of pharmacological intervention. However, a thorough evaluation to identify and address reversible causes of inadequate weight loss—such as maladaptive eating behaviors, inadequate physical activity, or anatomical issues like gastrogastric fistula—should always precede medication initiation. This evaluation should include nutritional assessment, physical activity review, psychological factors, and appropriate diagnostic testing (such as endoscopy when indicated). The decision should be individualized based on the patient's surgical procedure type, time since surgery, current metabolic status, and treatment goals.

Several injectable medications have received FDA approval for chronic weight management, though none carry specific labeling for use in post-bariatric surgery patients. Semaglutide (Wegovy), approved at a 2.4 mg weekly dose, represents the most potent GLP-1 receptor agonist currently available for weight management. Clinical trials in the general obesity population demonstrated average weight loss of approximately 15% of body weight over 68 weeks, with somewhat lower efficacy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Semaglutide requires gradual dose titration, starting at 0.25 mg weekly and increasing every 4 weeks to the target dose of 2.4 mg to minimize gastrointestinal side effects.

Liraglutide (Saxenda), administered as a daily 3.0 mg subcutaneous injection, was the first GLP-1 agonist approved specifically for weight management and produces average weight loss of 5-10% in clinical trials. Liraglutide is typically initiated at 0.6 mg daily and increased weekly by 0.6 mg increments to the target dose of 3.0 mg daily.

These medications work by mimicking the action of endogenous GLP-1, a gut hormone that regulates appetite and glucose metabolism. They slow gastric emptying, enhance satiety, reduce hunger, and improve glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. The mechanism of action overlaps substantially with the physiological changes produced by bariatric surgery itself, particularly Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy, which both increase endogenous GLP-1 secretion. This mechanistic overlap raises theoretical questions about additive benefit, though emerging evidence suggests that exogenous GLP-1 agonists can produce additional weight loss even in the altered post-surgical gut hormone environment.

Tirzepatide (Zepbound), a dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and GLP-1 receptor agonist, received FDA approval for chronic weight management in November 2023. With average weight loss exceeding 20% in clinical trials of non-diabetic patients with obesity, tirzepatide represents the most effective pharmacological option currently available. Tirzepatide is initiated at 2.5 mg weekly and increased every 4 weeks as tolerated to a maximum dose of 15 mg weekly. All these medications are contraindicated in patients with a personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma or Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia syndrome type 2 (MEN2), and should not be used during pregnancy.

The safety profile of weight loss injections in post-bariatric surgery patients requires special consideration due to the altered gastrointestinal anatomy and physiology created by surgical intervention. The most common adverse effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists—nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation—occur in 20-50% of patients in general populations. In post-bariatric patients, these gastrointestinal symptoms may be more pronounced or difficult to distinguish from surgical complications, potentially delaying recognition of serious issues such as bowel obstruction, internal hernia, or anastomotic ulceration.

Nutritional concerns represent a significant consideration in this population. Bariatric surgery patients already face lifelong risks of protein malnutrition and micronutrient deficiencies due to reduced intake capacity and, in malabsorptive procedures, impaired absorption. The appetite suppression and early satiety induced by GLP-1 agonists may further compromise nutritional intake, potentially exacerbating deficiencies in protein, iron, calcium, vitamin B12, and fat-soluble vitamins. Regular monitoring of nutritional markers becomes even more critical when these medications are added to a post-surgical regimen. Patients should be counseled to prioritize protein intake and maintain their prescribed supplementation schedule despite reduced appetite.

FDA-labeled warnings for these medications include acute pancreatitis, acute kidney injury from dehydration, acute gallbladder disease (including cholecystitis and cholelithiasis), and intestinal obstruction. Patients should be instructed to stop the medication and seek urgent medical care for severe or persistent abdominal pain (especially if radiating to the back), right upper quadrant pain with fever, inability to maintain adequate fluid intake for more than 24 hours, or decreased urine output.

The risk of hypoglycemia with GLP-1/GIP agonists is generally low unless combined with insulin or insulin secretagogues (sulfonylureas), which may require dose adjustment of those medications. Patients who have undergone Roux-en-Y gastric bypass may experience post-bariatric hypoglycemia, which requires separate evaluation. Patients should be counseled about symptoms requiring immediate medical attention and advised to avoid pregnancy while on these medications, discontinuing them prior to planned conception.

Emerging evidence suggests that weight loss injections can provide additional benefit for carefully selected post-bariatric surgery patients, though the data remains limited compared to the extensive literature supporting bariatric surgery alone. Several small observational studies and case series have reported that GLP-1 receptor agonists can produce meaningful additional weight loss in patients experiencing weight regain or inadequate initial weight loss following bariatric procedures. Additional weight loss of 5-15% of current body weight has been reported in these studies, though results vary considerably and most studies have limited follow-up duration.

The effectiveness of combining these therapies appears to depend on several factors. Patients who have undergone adjustable gastric banding, sleeve gastrectomy, or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass may respond differently, though high-quality comparative data is lacking. Individual responses vary substantially, and more research is needed to identify reliable predictors of response.

It is crucial to emphasize that weight loss injections should not be viewed as a rescue therapy for poor adherence to post-surgical lifestyle recommendations. Patients who have not maintained regular physical activity, continue to consume high-calorie beverages, or engage in grazing behaviors are unlikely to achieve optimal results from pharmacotherapy alone. The most successful outcomes occur when medications are used as part of a comprehensive approach that includes ongoing nutritional counseling, behavioral support, and exercise programming.

For patients who cannot tolerate injectable medications, other FDA-approved anti-obesity medications may be considered, including phentermine/topiramate ER, naltrexone/bupropion ER, or orlistat, though evidence for their use specifically in post-bariatric populations is even more limited. Additionally, the durability of weight loss achieved with these medications in post-bariatric patients remains uncertain, as most studies have followed patients for only 6-12 months. The need for indefinite medication continuation to maintain weight loss, along with associated costs and potential long-term safety concerns, must be factored into treatment decisions.

Patients considering weight loss injections after bariatric surgery should initiate this conversation with their bariatric surgery team rather than pursuing these medications independently through primary care or weight loss clinics unfamiliar with their surgical history. The bariatric team can provide essential context about the patient's surgical anatomy, post-operative course, and whether weight regain or inadequate loss represents a true plateau requiring intervention or reflects modifiable behavioral factors. A comprehensive re-evaluation should include assessment of eating patterns, physical activity levels, psychological factors, and potential anatomical complications before concluding that pharmacotherapy is appropriate.

During the consultation, patients should expect a thorough discussion of realistic expectations, as weight loss from medications in the post-bariatric setting may differ from results seen in medication-naive patients. The bariatric team should review the patient's nutritional status, including recent laboratory values for protein markers (albumin), complete blood count, iron studies, vitamin B12, folate, vitamin D, calcium, parathyroid hormone, zinc, copper, and thiamine. Monitoring should typically occur every 3-6 months in the first year of combined therapy and annually thereafter. Patients with existing deficiencies may need optimization before starting medications that could further compromise intake. The discussion should also address the financial implications of long-term medication use, as insurance coverage for weight loss medications varies considerably, and out-of-pocket costs can be substantial.

Key questions patients should ask include: What is the evidence for this medication specifically in patients with my type of surgery? How will we monitor for both effectiveness and potential complications? What nutritional modifications or additional supplementation might be necessary? What are the criteria for continuing or discontinuing the medication? Typically, continuation is recommended if at least 5% weight loss is achieved at the maximum tolerated dose after 3-6 months of treatment. Women of childbearing potential should discuss contraception, as these medications should be avoided during pregnancy and discontinued prior to planned conception.

The bariatric team should also discuss alternative or complementary interventions, such as surgical revision or conversion procedures for patients with anatomical issues, intensive behavioral therapy programs, or participation in post-bariatric support groups. A collaborative, individualized approach that considers the patient's complete medical history, surgical anatomy, current metabolic status, and personal goals offers the best opportunity for safe and effective use of weight loss injections in the post-bariatric surgery population.

Most clinicians consider weight loss injections 6-12 months post-operatively after the initial rapid weight loss phase, or when patients experience a plateau or weight regain despite adherence to post-surgical recommendations. Earlier initiation may be appropriate when significant comorbidities persist, but timing should be individualized based on surgical procedure type and metabolic status.

GLP-1 medications can be used safely in post-bariatric patients, but require careful monitoring due to potential gastrointestinal side effects and increased risk of nutritional deficiencies. Regular assessment of protein intake, micronutrient levels, and hydration status is essential, as these medications may further suppress appetite in patients already at risk for malnutrition.

Emerging evidence suggests GLP-1 receptor agonists can produce additional weight loss in post-bariatric patients, with studies reporting 5-15% additional body weight reduction. However, effectiveness depends on adherence to lifestyle modifications, and medications work best as part of a comprehensive approach including nutritional counseling, behavioral support, and exercise programming rather than as a standalone rescue therapy.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.