LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

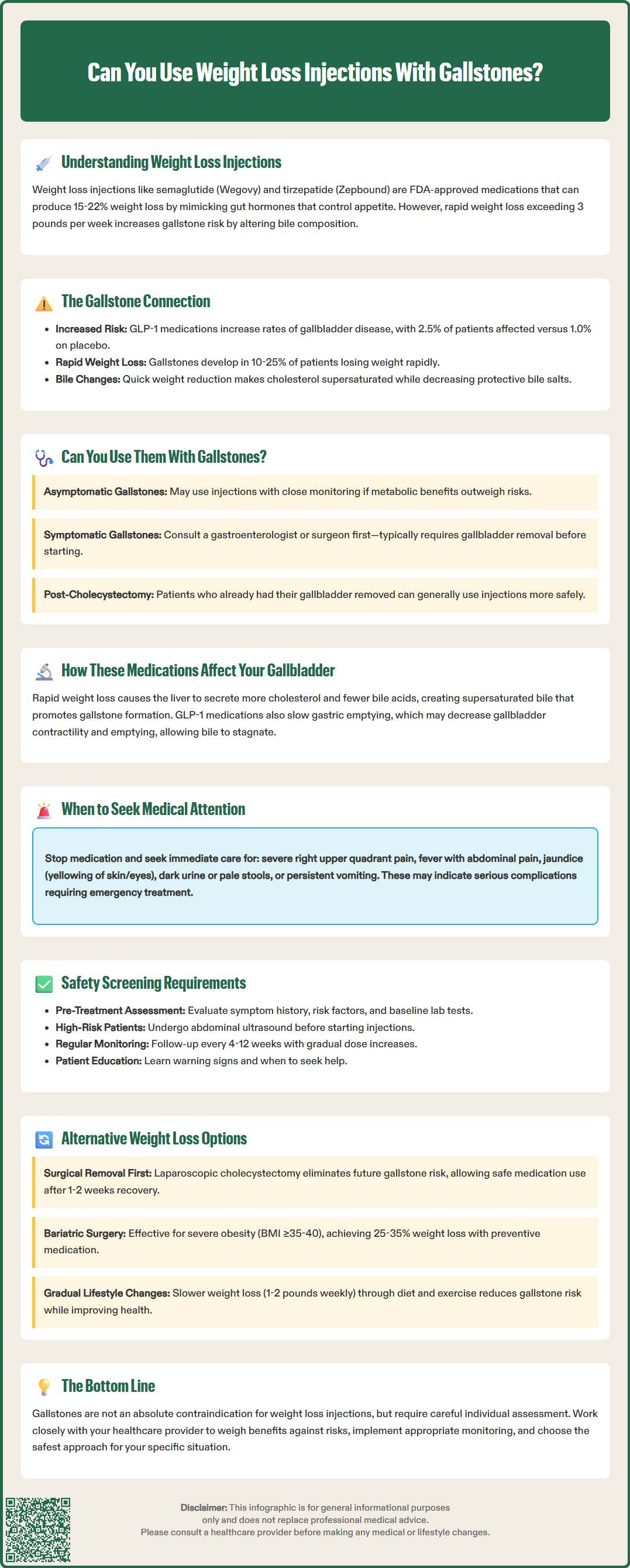

Can you use weight loss injections with gallstones? This question concerns many patients considering GLP-1 medications like semaglutide (Wegovy) or tirzepatide (Zepbound) for obesity management. While gallstones don't automatically prevent use of these FDA-approved weight loss injections, the decision requires careful medical evaluation. Rapid weight loss from these medications can increase gallstone formation risk and potentially trigger complications in those with existing stones. Understanding the relationship between incretin-based therapies and gallbladder health is essential for safe, effective treatment. This article examines when weight loss injections may be appropriate for patients with gallstones, necessary precautions, and alternative options.

Quick Answer: Weight loss injections can sometimes be used with gallstones, but require individualized medical assessment weighing benefits against gallbladder complication risks.

We offer compounded medications and Zepbound®. Compounded medications are prepared by licensed pharmacies and are not FDA-approved. References to Wegovy®, Ozempic®, Rybelsus®, Mounjaro®, or Saxenda®, or other GLP-1 brands, are informational only. Compounded and FDA-approved medications are not interchangeable.

Weight loss injections have transformed obesity management in recent years. These include glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists such as semaglutide (Wegovy, Ozempic) and liraglutide (Saxenda), as well as tirzepatide (Zepbound, Mounjaro), which is a dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and GLP-1 receptor agonist. These medications work by mimicking natural gut hormones that regulate appetite, slow gastric emptying, and enhance insulin secretion.

Importantly, only certain formulations are FDA-approved for chronic weight management—specifically Wegovy (semaglutide) and Zepbound (tirzepatide)—while Ozempic and Mounjaro are approved for type 2 diabetes management only. Clinical trials demonstrate substantial weight reduction with these medications: semaglutide typically produces approximately 15% weight loss in non-diabetic patients, while tirzepatide has shown up to 22% weight loss in clinical trials.

However, rapid weight loss from any cause carries an established risk of gallstone formation. Gallstones (cholelithiasis) are hardened deposits that form in the gallbladder, primarily composed of cholesterol or bilirubin. When weight loss exceeds 1.5 kg (approximately 3 pounds) per week, bile composition changes: cholesterol becomes supersaturated while bile salts and lecithin decrease, creating conditions favorable for stone formation. The risk varies by weight loss method, with very low calorie diets and bariatric surgery associated with gallstone formation in 10-25% of patients.

The relationship between incretin-based medications and gallbladder disease has gained attention following post-marketing surveillance and real-world data. FDA prescribing information for both semaglutide and tirzepatide notes cholelithiasis and cholecystitis (gallbladder inflammation) as adverse events. A 2022 systematic review and meta-analysis in JAMA Internal Medicine found increased rates of gallbladder or biliary disease among GLP-1 receptor agonist users compared to placebo or active comparators, with higher risk at weight-loss doses. Understanding this connection is essential for patients considering these therapies, particularly those with existing gallbladder concerns.

The presence of gallstones does not automatically disqualify patients from using weight loss injections, but it significantly complicates the clinical decision-making process. There is no absolute contraindication listed in FDA labeling for GLP-1 receptor agonists or tirzepatide specifically related to existing gallstones. However, the decision requires careful individualized assessment by a healthcare provider who can weigh potential benefits against risks.

Patients with asymptomatic gallstones (silent stones discovered incidentally on imaging) present a nuanced scenario. Many individuals have gallstones without symptoms—estimates suggest 10–15% of US adults have gallstones, with most remaining asymptomatic throughout life. For these patients, initiating weight loss injections may be considered if:

The potential metabolic benefits (improved diabetes control, cardiovascular risk reduction, weight loss) substantially outweigh gallbladder risks

Close monitoring is feasible with regular clinical follow-up

Patients understand warning signs of gallbladder complications

The rate of weight loss can be moderated through dosing strategies

Conversely, patients with symptomatic gallstones—experiencing biliary colic (right upper quadrant pain after meals), previous episodes of cholecystitis, or complications such as pancreatitis—generally should undergo evaluation by a gastroenterologist or surgeon before starting weight loss injections. The American College of Gastroenterology recommends cholecystectomy (surgical gallbladder removal) for symptomatic cholelithiasis, which would typically be performed before considering weight loss pharmacotherapy. This represents a shared decision-making opportunity between patient and providers.

For patients at high risk of gallstone formation during weight loss, ursodeoxycholic acid prophylaxis may be considered, particularly during periods of rapid weight reduction. This medication can help prevent gallstone formation by improving bile composition.

Patients with a history of cholecystectomy (gallbladder already removed) can generally use weight loss injections with lower gallbladder-specific risk, though other biliary tract complications remain possible. This represents a more straightforward scenario for proceeding with incretin-based therapy in someone with previous gallstone disease, though standard contraindications still apply.

Weight loss injections influence gallbladder health through multiple interconnected mechanisms. Understanding these pathways helps clarify why gallbladder complications occur and informs risk mitigation strategies.

Rapid Weight Loss and Bile Composition: The primary mechanism involves the metabolic changes accompanying significant weight reduction. During rapid weight loss, the liver secretes increased cholesterol into bile while simultaneously reducing bile acid output. This creates supersaturated bile with elevated cholesterol saturation index, promoting crystal nucleation and stone formation. Additionally, weight loss reduces gallbladder motility—the organ contracts less frequently and less completely, allowing bile stasis that facilitates stone development.

Incretin-Specific Effects: Beyond weight loss itself, GLP-1 receptor agonists and dual GIP/GLP-1 agonists may have effects on gallbladder function. These medications slow gastric emptying as part of their mechanism to reduce appetite and food intake. Some research suggests this delayed gastric emptying might extend to reduced gallbladder contractility and emptying, though this remains an area of ongoing investigation with limited evidence. Some studies have identified GLP-1 receptors in gallbladder tissue, potentially mediating effects on gallbladder motor function.

Inflammatory Risk: Existing gallstones may become symptomatic during weight loss treatment. Stones can migrate from the gallbladder into the bile ducts (choledocholithiasis), potentially causing obstruction, jaundice, or acute pancreatitis. The inflammatory cascade triggered by stone impaction can lead to acute cholecystitis, a surgical emergency requiring urgent intervention.

According to FDA prescribing information, gallbladder-related adverse events occurred in clinical trials of semaglutide for weight management (Wegovy) at rates of 2.5% versus 1.0% with placebo, and for tirzepatide (Zepbound) at rates of 2.5% versus 1.0% with placebo. The risk appears dose-dependent, with higher rates observed at weight-loss doses compared to diabetes treatment doses. While the absolute risk increase appears modest, it represents a clinically meaningful elevation requiring patient counseling and monitoring protocols.

Comprehensive medical evaluation before initiating weight loss injections is essential to identify gallbladder disease and stratify risk appropriately. This screening process should include detailed history-taking, physical examination, and selective use of diagnostic imaging.

Pre-Treatment Assessment should evaluate:

Symptom history: Right upper quadrant or epigastric pain, especially postprandial (after eating); nausea; fatty food intolerance; previous episodes of jaundice

Risk factors: Female sex, age over 40, obesity, rapid previous weight loss, pregnancy history, family history of gallstones, certain ethnicities (Native American, Hispanic heritage)

Physical examination: Right upper quadrant tenderness, Murphy's sign (inspiratory arrest during right subcostal palpation)

Laboratory testing: Liver function tests may be considered based on clinical judgment to establish baseline and screen for biliary obstruction

Imaging considerations: Routine abdominal ultrasound before starting weight loss injections is not recommended for asymptomatic patients. However, ultrasound should be considered for patients with:

Suggestive symptoms or examination findings

Significantly elevated liver enzymes

History of previous biliary symptoms

Ongoing Monitoring during treatment includes:

Regular clinical follow-up (typically every 4–12 weeks initially)

Patient education about warning symptoms requiring urgent evaluation

Periodic liver function monitoring if clinically indicated

Gradual dose titration to moderate weight loss velocity when feasible

Red Flag Symptoms requiring immediate medical attention include:

Severe, persistent right upper quadrant or epigastric pain

Fever with abdominal pain

Jaundice (yellowing of skin or eyes)

Dark urine or pale stools

Persistent nausea and vomiting

Patients experiencing these symptoms should seek urgent medical evaluation. If pancreatitis is suspected or confirmed, the medication should be discontinued as specified in FDA prescribing information. For other biliary symptoms, temporarily holding the medication pending evaluation is appropriate.

It's important to note that these medications have additional contraindications unrelated to gallbladder disease, including personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma, Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia syndrome type 2, pregnancy, and caution is advised with history of pancreatitis or severe gastrointestinal disease.

For patients with symptomatic gallstones or those at particularly high risk for gallbladder complications, several alternative weight loss approaches merit consideration. The optimal strategy depends on individual circumstances, comorbidities, and treatment goals.

Surgical Management First: For patients with symptomatic gallstones who are appropriate surgical candidates, laparoscopic cholecystectomy followed by weight loss therapy represents a logical sequence. This minimally invasive procedure removes the gallbladder, eliminating future gallstone risk and allowing subsequent use of weight loss injections if desired. Recovery typically requires 1–2 weeks, after which metabolic management can proceed without gallbladder-specific constraints. This approach is particularly appropriate for patients with obesity and symptomatic cholelithiasis who would benefit from both interventions.

Bariatric Surgery: For patients with severe obesity (BMI ≥40 kg/m² or ≥35 kg/m² with comorbidities), metabolic and bariatric surgery offers substantial, durable weight loss. Procedures such as sleeve gastrectomy or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass achieve 25–35% total body weight loss. While cholecystectomy can be performed simultaneously with bariatric surgery if symptomatic gallstones are present, routine prophylactic cholecystectomy is not generally recommended. Instead, ursodeoxycholic acid prophylaxis for 6 months post-operatively is often used to reduce gallstone formation risk during rapid weight loss.

Lifestyle Modification with Medical Support: Structured lifestyle intervention remains foundational for weight management. Comprehensive programs incorporating:

Nutritional counseling emphasizing gradual caloric reduction (500–750 kcal/day deficit)

Regular physical activity (≥150 minutes weekly moderate-intensity exercise)

Behavioral therapy and support groups

Slower weight loss targets (0.5–1 kg or 1–2 pounds weekly)

This approach minimizes gallstone formation risk through gradual weight reduction while still achieving meaningful health benefits. Even modest weight loss of 5-10% can significantly improve metabolic health. The American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and The Obesity Society endorse lifestyle therapy as first-line treatment for overweight and obesity.

Alternative Pharmacotherapy: Other weight loss medications may present different risk profiles:

Phentermine-topiramate (Qsymia): Combination therapy with different mechanisms; less data on gallbladder effects

Naltrexone-bupropion (Contrave): Targets central appetite regulation; limited gallstone association data

Orlistat (Xenical, Alli): Lipase inhibitor reducing fat absorption; provides more modest weight loss (5–10%) with significant gastrointestinal side effects

Each alternative carries distinct benefits, risks, and efficacy profiles requiring individualized discussion with healthcare providers. The decision should integrate patient preferences, comorbidity burden, previous treatment responses, and specific contraindications to create a personalized, safe weight management strategy.

Weight loss injections increase gallstone risk primarily through rapid weight reduction, which alters bile composition and reduces gallbladder motility. Clinical trials show gallbladder-related events occur in approximately 2.5% of patients using these medications compared to 1.0% with placebo.

Routine cholecystectomy is not recommended before weight loss injections. However, patients with symptomatic gallstones should typically undergo surgical evaluation and possible gallbladder removal before starting these medications to prevent complications during treatment.

Seek immediate medical attention for severe right upper quadrant pain, fever with abdominal pain, jaundice (yellowing of skin or eyes), dark urine, pale stools, or persistent nausea and vomiting. These symptoms may indicate acute cholecystitis, bile duct obstruction, or pancreatitis requiring urgent evaluation.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.