LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

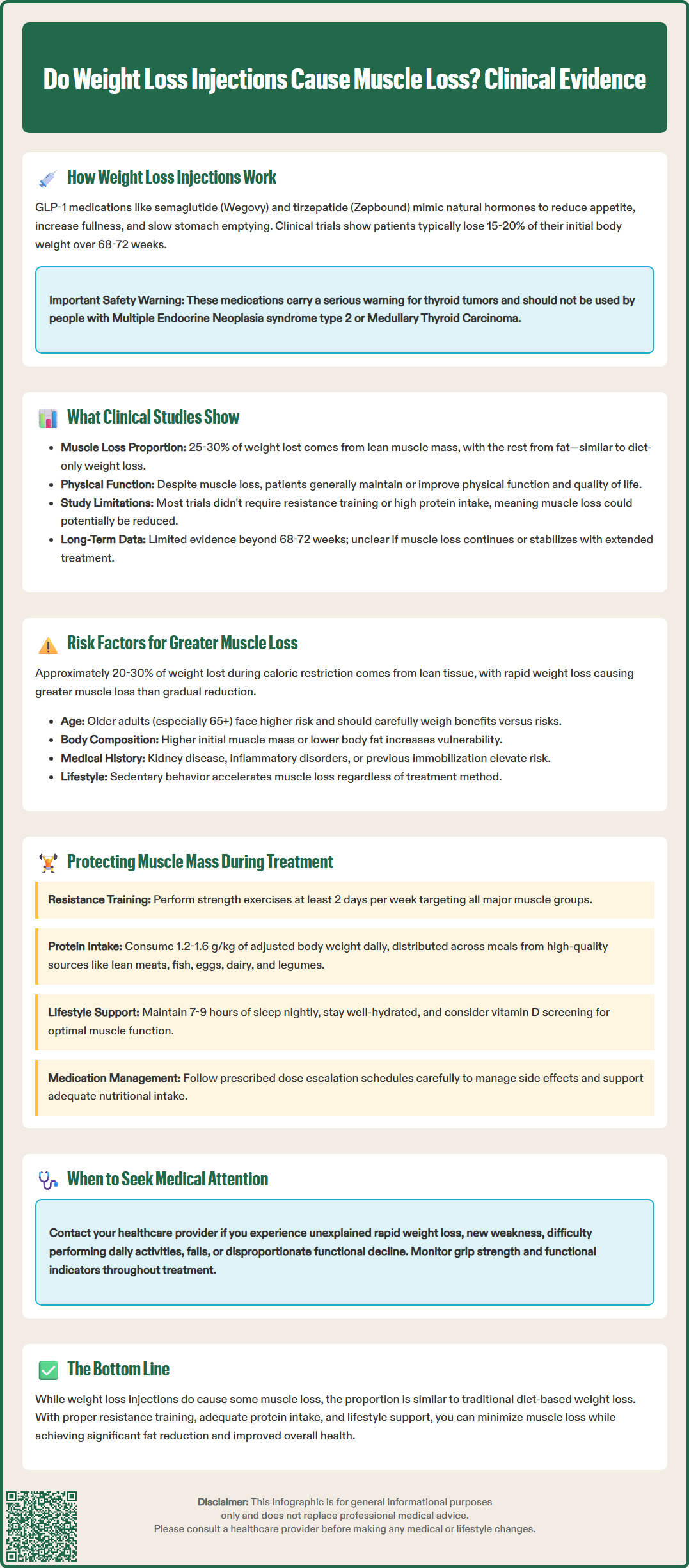

Do weight loss injections cause muscle loss? This question concerns many patients considering GLP-1 receptor agonists like semaglutide (Wegovy) and tirzepatide (Zepbound) for chronic weight management. Clinical evidence shows that approximately 25-30% of weight lost during treatment comes from lean tissue, including muscle—a proportion similar to other weight loss methods. However, this muscle loss isn't inevitable. With targeted interventions including resistance training and adequate protein intake, patients can significantly preserve muscle mass while achieving substantial fat reduction. Understanding the mechanisms behind muscle loss and evidence-based protective strategies helps patients and healthcare providers optimize body composition outcomes during GLP-1 therapy.

Quick Answer: Weight loss injections cause some muscle loss, with approximately 25-30% of total weight lost coming from lean tissue, similar to other weight loss methods.

We offer compounded medications and Zepbound®. Compounded medications are prepared by licensed pharmacies and are not FDA-approved. References to Wegovy®, Ozempic®, Rybelsus®, Mounjaro®, or Saxenda®, or other GLP-1 brands, are informational only. Compounded and FDA-approved medications are not interchangeable.

Weight loss injections, primarily glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, include FDA-approved medications for chronic weight management such as semaglutide (Wegovy) and tirzepatide (Zepbound). Similar medications—semaglutide (Ozempic) and tirzepatide (Mounjaro)—are FDA-approved for type 2 diabetes management, though sometimes used off-label for weight loss.

These medications work through multiple physiological mechanisms to promote weight reduction by mimicking naturally occurring incretin hormones that regulate glucose metabolism and appetite control.

The primary mechanism involves binding to GLP-1 receptors in the pancreas, brain, and gastrointestinal tract. In the pancreas, these agents enhance glucose-dependent insulin secretion while suppressing glucagon release, improving glycemic control. Centrally, GLP-1 receptor agonists act on hypothalamic appetite centers to increase satiety and reduce hunger signals. Additionally, these medications slow gastric emptying, prolonging the sensation of fullness after meals and reducing overall caloric intake.

Tirzepatide offers dual agonist activity, targeting both GLP-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) receptors, which may enhance weight loss efficacy compared to single-receptor agonists. The resulting caloric deficit from reduced food intake drives substantial weight loss—typically 15-20% of initial body weight over 68-72 weeks in clinical trials.

During any significant weight loss, the body mobilizes energy stores from both adipose tissue and skeletal muscle. Without specific interventions like resistance exercise and adequate protein intake, a portion of weight loss typically comes from lean tissue, raising important questions about body composition changes during GLP-1 therapy.

Importantly, these medications carry a boxed warning for thyroid C-cell tumors and are contraindicated in patients with Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia syndrome type 2 (MEN2) or Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma (MTC).

Multiple variables determine the extent of muscle loss during weight loss injection therapy, with the rate and magnitude of weight reduction being paramount. Rapid weight loss—regardless of method—typically results in greater proportional lean mass loss compared to gradual reduction. Studies suggest that approximately 20-30% of total weight lost during caloric restriction comes from lean tissue, including skeletal muscle, though this percentage varies considerably based on individual circumstances.

Key factors affecting muscle preservation include:

Baseline body composition: Individuals with higher initial muscle mass and lower body fat percentages may experience more pronounced muscle loss during weight reduction

Protein intake adequacy: Insufficient dietary protein (below 0.8-1.0 g/kg/day, and ideally 1.2-1.6 g/kg of adjusted body weight for those losing weight) compromises muscle protein synthesis

Physical activity levels: Sedentary behavior during treatment accelerates muscle catabolism, while resistance training provides protective stimulus

Age: Older adults face greater risk due to age-related sarcopenia and reduced anabolic response to dietary protein

Medication dosage and duration: Higher doses and longer treatment periods associated with greater total weight loss may potentially result in more absolute muscle loss, though this relationship requires further study

The hormonal environment during weight loss also influences muscle preservation. Caloric restriction can trigger adaptive responses that may affect muscle metabolism, though these effects vary considerably between individuals. While GLP-1 receptor agonists may influence some metabolic pathways, they do not eliminate the fundamental challenge of preserving lean mass during energy deficit.

Patients with pre-existing conditions affecting muscle health—such as chronic kidney disease (who require individualized protein recommendations), inflammatory disorders, or previous prolonged immobilization—face elevated risk and warrant closer monitoring during treatment.

Red flags requiring medical attention include unexplained rapid weight loss, new-onset weakness, difficulty with daily activities, or falls. These symptoms should prompt evaluation by a healthcare provider and potential referral to a registered dietitian or physical therapist.

Evidence-based strategies can significantly reduce muscle loss during GLP-1 receptor agonist therapy, with resistance exercise and adequate protein intake forming the cornerstone of muscle preservation protocols. Healthcare providers should counsel patients on these interventions before initiating treatment and monitor adherence throughout the weight loss journey.

Resistance training represents the most effective intervention for maintaining muscle mass during caloric restriction. According to the American College of Sports Medicine and U.S. Physical Activity Guidelines, adults should perform resistance exercises targeting all major muscle groups at least 2 days per week. Progressive resistance exercise—using weights, resistance bands, or bodyweight exercises—provides the mechanical stimulus necessary to preserve muscle protein synthesis despite energy deficit. For individuals new to exercise, consultation with a physical therapist or certified exercise professional can ensure safe, appropriate programming.

Protein optimization requires deliberate attention, as the appetite suppression from GLP-1 agonists often reduces overall food intake, potentially compromising protein consumption. Current evidence supports protein intake of 1.2-1.6 g/kg of adjusted body weight daily during active weight loss, distributed across meals to maximize muscle protein synthesis. High-quality protein sources—lean meats, fish, eggs, dairy, legumes, and soy products—should be prioritized at each meal. Patients with chronic kidney disease should consult their healthcare provider for individualized protein recommendations. Those struggling to meet protein targets through whole foods may benefit from protein supplementation, though whole food sources remain preferable when feasible.

Additional protective strategies include:

Medication titration: Following prescribed dose escalation schedules helps manage side effects and may support adequate nutritional intake

Adequate hydration: Maintaining fluid balance supports muscle function and recovery from exercise

Sufficient sleep: Seven to nine hours nightly supports recovery and overall metabolic health

Vitamin D assessment: Screening for vitamin D deficiency and appropriate supplementation based on individual needs

While body composition testing (such as dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry or bioelectrical impedance analysis) can provide useful information in some cases, it is not routinely required for all patients. Functional assessments—such as grip strength, chair stand tests, or observed physical performance—often provide practical insights into muscle health. Concerning findings such as disproportionate weakness, difficulty with daily activities, or functional decline warrant consultation with healthcare providers, who may recommend physical therapy, nutritional consultation, or treatment adjustments.

Clinical trial data examining body composition changes during GLP-1 receptor agonist therapy reveal consistent patterns of lean mass reduction alongside fat loss, though the magnitude and clinical significance remain subjects of ongoing investigation. The STEP (Semaglutide Treatment Effect in People with obesity) trials and SURMOUNT (tirzepatide) studies provide the most comprehensive evidence to date.

In the STEP 1 trial, participants receiving semaglutide 2.4 mg weekly lost an average of 14.9% of initial body weight over 68 weeks. Body composition analysis in substudies revealed that approximately 25-30% of total weight lost came from lean mass, with the remainder from fat mass. Similarly, the SURMOUNT-1 trial demonstrated that participants receiving tirzepatide 15 mg weekly lost approximately 20.9% of body weight, with lean mass comprising roughly 25-30% of total loss based on available data. These proportions are generally consistent with expected lean mass loss during caloric restriction achieved through other methods, suggesting GLP-1 agonists do not uniquely accelerate muscle catabolism beyond what occurs with equivalent weight loss from dietary intervention alone.

However, important caveats warrant consideration. Most pivotal trials did not mandate structured resistance training or specific protein intake targets, potentially underestimating the muscle preservation achievable with comprehensive lifestyle intervention. Analyses from weight loss studies suggest that participants who maintain higher physical activity levels and adequate protein intake typically experience better lean mass preservation.

Functional outcomes provide additional context. Despite measurable lean mass reduction, clinical trials have generally not demonstrated significant declines in patient-reported physical function among participants. The STEP 4 trial showed maintained or improved scores on health-related quality of life measures despite continued weight loss. This apparent paradox may reflect the substantial metabolic and mechanical benefits of fat mass reduction offsetting modest muscle loss, particularly in weight-bearing activities.

Limited data suggest potential age-related differences in body composition outcomes. Older adults (≥65 years) may experience different responses during GLP-1 therapy. The FDA labels for both Wegovy and Zepbound note that clinical experience in patients aged 75 years and older is limited, and careful risk-benefit assessment is warranted in older adults with pre-existing low muscle mass.

Long-term data remain limited, with most trials extending only 68-72 weeks. Whether lean mass loss continues, stabilizes, or partially recovers during extended treatment or after medication discontinuation requires further study. Preliminary evidence suggests that weight regain after stopping GLP-1 agonists may involve changes in body composition, though more research is needed to understand these patterns and their clinical significance.

Clinical trials show that approximately 25-30% of total weight lost during GLP-1 receptor agonist therapy comes from lean tissue, including muscle. This proportion is similar to muscle loss observed with other weight loss methods and can be reduced through resistance training and adequate protein intake.

Yes, resistance training at least 2 days per week combined with protein intake of 1.2-1.6 g/kg of adjusted body weight daily significantly reduces muscle loss during GLP-1 therapy. These evidence-based interventions help preserve lean mass while promoting fat loss.

Older adults may face greater risk due to age-related sarcopenia and reduced anabolic response to protein. Healthcare providers should carefully assess risk-benefit ratios in patients aged 65 and older, particularly those with pre-existing low muscle mass, and emphasize muscle preservation strategies.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.