LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

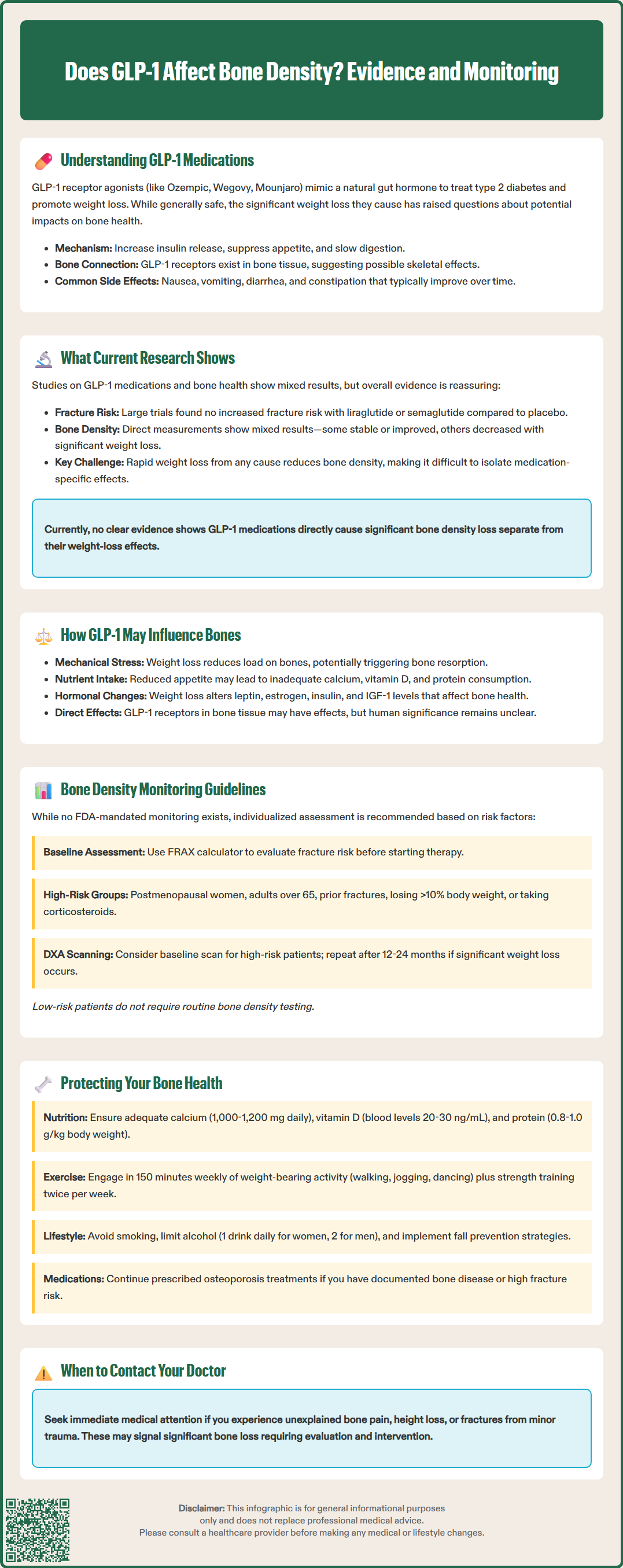

GLP-1 receptor agonists like semaglutide and liraglutide have transformed type 2 diabetes and weight management, but questions persist about their effects on skeletal health. Does GLP-1 affect bone density? Current evidence suggests these medications do not directly cause clinically significant bone loss, though the substantial weight reduction they produce may indirectly influence bone metabolism. Understanding the relationship between GLP-1 therapy and bone health helps clinicians and patients make informed treatment decisions while implementing appropriate monitoring and protective strategies for skeletal integrity during therapy.

Quick Answer: GLP-1 receptor agonists have not been definitively shown to directly cause clinically significant bone density loss, though the substantial weight reduction they produce may indirectly affect bone metabolism.

We offer compounded medications and Zepbound®. Compounded medications are prepared by licensed pharmacies and are not FDA-approved. References to Wegovy®, Ozempic®, Rybelsus®, Mounjaro®, or Saxenda®, or other GLP-1 brands, are informational only. Compounded and FDA-approved medications are not interchangeable.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists represent a class of medications primarily used for managing type 2 diabetes mellitus and, more recently, for chronic weight management. These agents include semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy), dulaglutide (Trulicity), liraglutide (Victoza, Saxenda), and others. Tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Zepbound) is a dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist with a slightly different mechanism. Understanding their mechanism of action provides essential context for evaluating potential effects on bone health.

GLP-1 is an incretin hormone naturally produced by intestinal L-cells in response to food intake. GLP-1 receptor agonists mimic this endogenous hormone by binding to GLP-1 receptors located throughout the body, including the pancreas, brain, gastrointestinal tract, and cardiovascular system. Their primary therapeutic effects include glucose-dependent insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells, suppression of inappropriate glucagon release, delayed gastric emptying, and reduced appetite through central nervous system pathways.

The glucose-dependent mechanism of insulin release distinguishes GLP-1 agonists from many other antidiabetic medications, resulting in a lower risk of hypoglycemia when used as monotherapy. However, this risk increases when combined with insulin or sulfonylureas. The appetite suppression and delayed gastric emptying contribute to significant weight loss, which has expanded their clinical applications beyond diabetes management. Common adverse effects include gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation, which typically diminish over time with dose titration.

GLP-1 receptors have been identified in various tissues beyond those directly involved in glucose metabolism, raising questions about broader physiological effects. Preclinical studies suggest the presence of these receptors in bone tissue and cells involved in bone remodeling, though this remains an area of ongoing investigation in humans. This has prompted research into whether GLP-1 therapy influences skeletal health, particularly given the substantial weight loss these medications can produce.

The relationship between GLP-1 receptor agonists and bone density remains an area of active investigation, with emerging but not yet definitive evidence. Current research presents a complex picture that requires careful interpretation, as studies have yielded mixed results depending on the specific agent studied, patient population, duration of treatment, and methodology employed.

Preclinical studies have suggested that GLP-1 receptors may be expressed on osteoblasts (bone-forming cells) and osteoclasts (bone-resorbing cells), primarily in animal models. These findings suggest a potential direct role in bone metabolism. Some animal studies have shown that GLP-1 receptor activation may promote osteoblast activity and inhibit osteoclast function, theoretically favoring bone formation over resorption. However, translating these findings to human clinical outcomes requires caution, as animal models do not always predict human responses accurately, and the presence and function of these receptors in human bone cells remain debated.

Clinical trials and observational studies in humans have produced variable findings. Some cardiovascular outcome trials, such as the LEADER trial with liraglutide and the SUSTAIN-6 trial with semaglutide, included fracture events as safety endpoints. These large studies did not identify increased fracture risk compared to placebo, providing some reassurance regarding skeletal safety. However, these trials were not specifically designed to assess bone density changes or fracture risk as primary outcomes.

More targeted research examining bone turnover markers and bone mineral density (BMD) measurements has shown inconsistent results. Some studies report stable or slightly improved bone density with GLP-1 therapy, while others suggest potential decreases, particularly in the context of significant weight loss. A critical consideration is that rapid weight loss from any cause—whether through medication, surgery, or lifestyle modification—is associated with bone density reduction, making it challenging to isolate the independent effect of GLP-1 medications from the effect of weight loss itself. Currently, there is no definitive consensus that GLP-1 receptor agonists directly cause clinically significant bone density loss independent of their weight-reducing effects.

Several mechanisms may explain how GLP-1 therapy could theoretically influence bone health, though the clinical significance of these pathways remains under investigation. Understanding these potential mechanisms helps clinicians counsel patients and implement appropriate monitoring strategies.

Weight Loss and Mechanical Unloading: The most significant factor affecting bone density in patients taking GLP-1 medications is likely the substantial weight loss these agents produce. Weight-bearing mechanical stress is a primary stimulus for bone maintenance and remodeling. When patients lose significant weight—particularly rapidly—the reduced mechanical loading on the skeleton can trigger bone resorption. Studies of bariatric surgery consistently demonstrate bone density decreases following major weight loss, and similar patterns may occur with pharmacologically induced weight reduction. While the relationship between weight loss magnitude and bone loss is complex, patients with more substantial weight reduction may require closer monitoring.

Nutritional Factors: GLP-1 medications reduce appetite and food intake, which can inadvertently decrease consumption of nutrients essential for bone health, including calcium, vitamin D, and protein. While delayed gastric emptying occurs with these medications, it typically does not significantly impair nutrient absorption. Rather, the primary concern is reduced overall nutritional intake, especially in patients experiencing persistent gastrointestinal symptoms or significantly restricted eating patterns. Patients with limited dietary variety may be at higher risk for nutritional inadequacies that could compromise bone health.

Hormonal Changes: Weight loss affects multiple hormonal systems relevant to bone metabolism. Adipose tissue produces hormones such as leptin and estrogen (through aromatization of androgens), both of which influence bone density. Fat mass reduction can potentially alter these hormonal pathways, though the net clinical effect varies among individuals. Additionally, changes in insulin and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) levels associated with improved glycemic control may have complex effects on bone remodeling.

Direct Receptor-Mediated Effects: While preclinical studies suggest GLP-1 receptors may be present in bone tissue, the clinical relevance of direct receptor activation in human bone cells remains uncertain and controversial. The net effect of potential receptor activation in the context of other metabolic changes is unclear and requires further investigation.

It's worth noting that type 2 diabetes itself is associated with an increased fracture risk despite often normal or higher bone mineral density, which may complicate the interpretation of bone health outcomes in this population.

Currently, there are no specific FDA-mandated bone density monitoring requirements for patients prescribed GLP-1 receptor agonists, as these medications have not been definitively linked to increased fracture risk or clinically significant bone loss in regulatory reviews. However, clinicians should consider individualized assessment based on patient-specific risk factors and clinical circumstances.

Baseline Risk Assessment: Before initiating GLP-1 therapy, clinicians should evaluate baseline fracture risk using established tools such as the FRAX (Fracture Risk Assessment Tool) calculator, which incorporates age, sex, body mass index, prior fractures, family history, and other clinical risk factors. The U.S.-calibrated FRAX tool provides 10-year fracture probability estimates to guide clinical decision-making. Patients with pre-existing osteoporosis, osteopenia, or elevated fracture risk may warrant baseline dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scanning to establish a reference point for future comparison.

High-Risk Populations Requiring Consideration: Certain patient groups may benefit from more vigilant bone health monitoring during GLP-1 therapy:

Postmenopausal women, particularly those with additional risk factors

Older adults (age >65 years) with multiple comorbidities

Patients with prior fragility fractures or documented low bone density

Individuals losing >10% of body weight or experiencing rapid weight loss

Patients with concurrent use of medications affecting bone metabolism (corticosteroids, aromatase inhibitors, anticonvulsants)

Those with malabsorption disorders or inadequate nutritional intake

Monitoring Intervals: For patients deemed at higher risk, DXA scanning at baseline and repeated after 12-24 months of therapy may be reasonable, particularly if substantial weight loss has occurred. This interval aligns with recommendations from the Bone Health and Osteoporosis Foundation (BHOF) and allows sufficient time to detect clinically meaningful changes in bone density while enabling timely intervention if significant loss is identified. Bone turnover markers (such as C-terminal telopeptide and procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide) may provide earlier signals of altered bone metabolism, though their routine use is not standard practice in general clinical settings.

Clinical Judgment: Monitoring decisions should be individualized based on the balance of fracture risk factors, expected weight loss, treatment duration, and patient preferences. Not all patients require formal bone density assessment, and clinicians should avoid unnecessary testing in low-risk individuals. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening for osteoporosis in women aged 65 years and older and in younger women whose fracture risk is equal to or greater than that of a 65-year-old white woman with no additional risk factors.

Patients prescribed GLP-1 receptor agonists can take proactive steps to protect bone health during treatment, with guidance from their healthcare providers. These strategies address modifiable risk factors and optimize conditions for bone maintenance despite weight loss.

Nutritional Optimization: Adequate intake of bone-essential nutrients is critical during GLP-1 therapy. Patients should aim for:

Calcium: 1,000-1,200 mg daily from dietary sources (dairy products, fortified foods, leafy greens) or supplements if dietary intake is insufficient. Total calcium intake (diet plus supplements) should not exceed 2,000-2,500 mg daily to avoid potential adverse effects.

Vitamin D: The Bone Health and Osteoporosis Foundation (BHOF) and Endocrine Society recommend maintaining serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels above 30 ng/mL, while the National Academy of Medicine considers levels ≥20 ng/mL sufficient. Supplementation (typically 1,000-2,000 IU daily) and sensible sun exposure may be needed to achieve target levels.

Protein: Adequate protein intake (0.8-1.0 g/kg body weight daily, or higher for older adults) supports both muscle and bone health during weight loss.

Patients experiencing persistent nausea or reduced appetite should consider consultation with a registered dietitian to ensure nutritional adequacy despite lower food volumes. Small, frequent, nutrient-dense meals may be better tolerated than larger portions.

Weight-Bearing Exercise: Regular physical activity, particularly weight-bearing and resistance exercises, provides mechanical stimulus essential for bone maintenance. Recommended activities include walking, jogging, dancing, stair climbing, and strength training with weights or resistance bands. The U.S. Physical Activity Guidelines recommend at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity weekly, plus muscle-strengthening activities on 2 or more days per week. Exercise also helps preserve lean muscle mass during weight loss, which indirectly supports bone health.

Lifestyle Modifications: Patients should avoid or minimize factors that accelerate bone loss, including smoking cessation and limiting alcohol consumption to no more than one drink daily for women or two for men. Fall prevention strategies become increasingly important for older adults, including home safety assessments, vision correction, and medication reviews to minimize fall risk. The CDC's STEADI (Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths & Injuries) program provides resources for fall prevention.

Medical Management: For patients with documented osteoporosis or high fracture risk, pharmacologic bone-protective therapy may be indicated regardless of GLP-1 use. Bisphosphonates, denosumab, or other osteoporosis medications should be considered based on standard clinical guidelines. Patients should not discontinue necessary bone-protective treatments due to concerns about GLP-1 therapy.

When to Seek Medical Advice: Patients should contact their healthcare provider if they experience unexplained bone pain, height loss, or fractures with minimal trauma, as these may indicate significant bone loss requiring evaluation and intervention. Referral to an endocrinologist or osteoporosis specialist may be appropriate for patients with fragility fractures or very low bone mineral density. Regular follow-up visits provide opportunities to reassess bone health status and adjust protective strategies as needed.

Large clinical trials such as LEADER and SUSTAIN-6 have not identified increased fracture risk with GLP-1 therapy compared to placebo. However, these studies were not specifically designed to assess bone health as a primary outcome.

Baseline bone density testing is not routinely required for all patients but may be appropriate for those at higher risk, including postmenopausal women, older adults, individuals with prior fractures, or those with documented osteopenia or osteoporosis.

Ensure adequate calcium (1,000-1,200 mg daily) and vitamin D intake, consume sufficient protein, engage in regular weight-bearing and resistance exercise, avoid smoking, and limit alcohol consumption. Patients with documented osteoporosis may require specific bone-protective medications.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.