LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

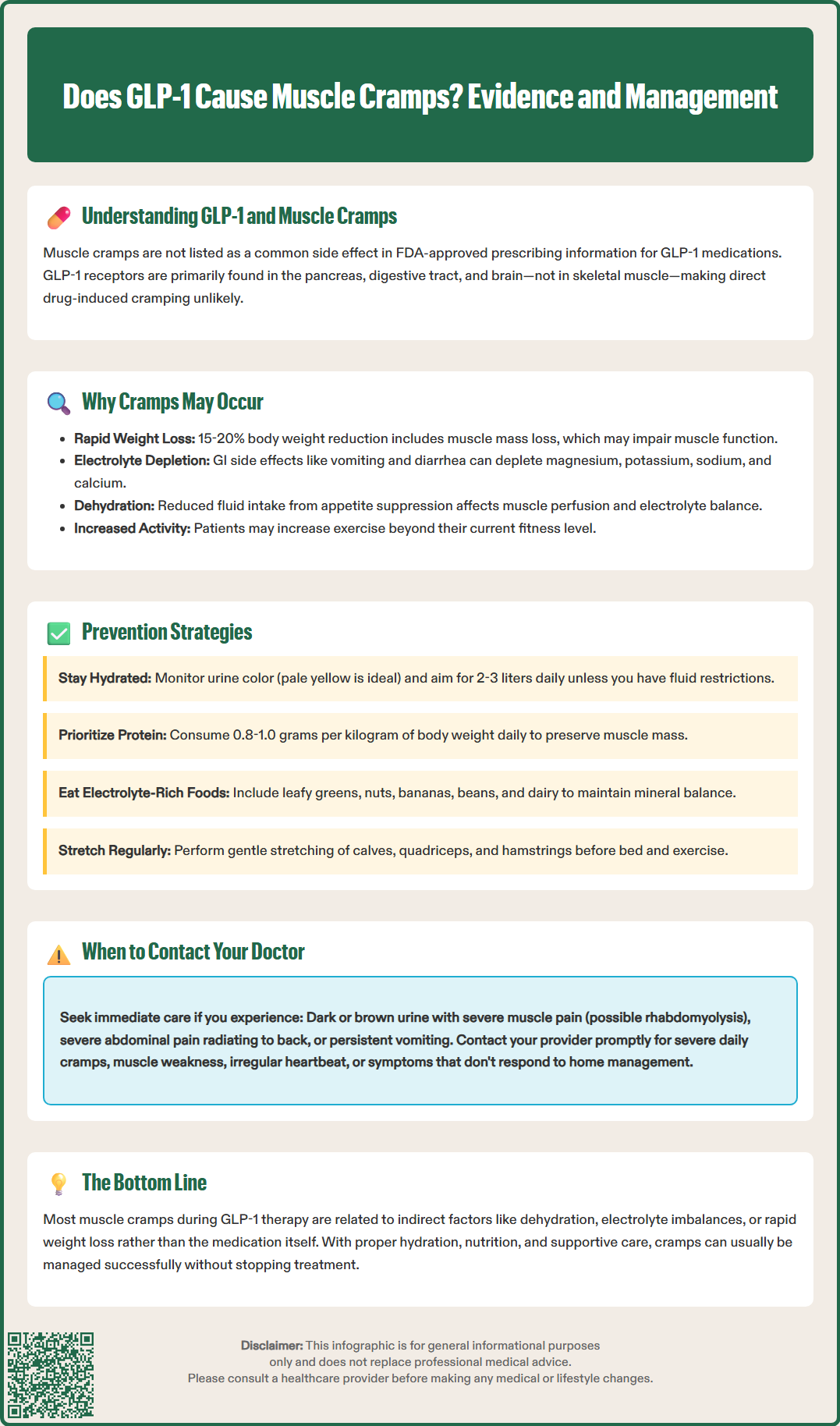

Does GLP-1 cause muscle cramps? This question arises frequently among patients prescribed glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists like semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy) and tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Zepbound) for type 2 diabetes or weight management. While muscle cramps are not listed as a common side effect in FDA labeling, some patients report experiencing them during treatment. Understanding the potential indirect mechanisms—including rapid weight loss, electrolyte disturbances, and dehydration—can help patients and clinicians manage these symptoms effectively. This article examines the evidence, explores possible causes, and provides practical strategies for prevention and management of muscle cramps during GLP-1 therapy.

Quick Answer: GLP-1 medications do not directly cause muscle cramps through pharmacologic action, but some patients may experience cramping indirectly due to rapid weight loss, electrolyte disturbances, or dehydration associated with treatment.

We offer compounded medications and Zepbound®. Compounded medications are prepared by licensed pharmacies and are not FDA-approved. References to Wegovy®, Ozempic®, Rybelsus®, Mounjaro®, or Saxenda®, or other GLP-1 brands, are informational only. Compounded and FDA-approved medications are not interchangeable.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists represent a class of medications increasingly prescribed for type 2 diabetes management and, more recently, for chronic weight management. These agents include semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy), dulaglutide (Trulicity), liraglutide (Victoza, Saxenda), and others. Tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Zepbound) is a dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist with a slightly different mechanism. These medications work by mimicking the action of naturally occurring incretin hormones, which enhance glucose-dependent insulin secretion, suppress inappropriate glucagon release, slow gastric emptying, and promote satiety through central nervous system pathways.

The most commonly reported adverse effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists are gastrointestinal in nature. According to FDA prescribing information, these include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, and abdominal discomfort. These symptoms typically occur during treatment initiation or dose escalation and often diminish over time as physiologic adaptation occurs. The gastrointestinal effects result primarily from delayed gastric emptying and altered gut motility.

Other important safety considerations include injection site reactions, increased heart rate (a class effect, though potentially more pronounced with liraglutide), and risk of pancreatitis (which requires immediate discontinuation if suspected). Most GLP-1 receptor agonists carry a boxed warning for thyroid C-cell tumors and are contraindicated in patients with personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma or Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia syndrome type 2. Additional labeled risks include gallbladder disease, acute kidney injury (particularly with severe gastrointestinal adverse events), and potential worsening of diabetic retinopathy complications with semaglutide. Hypoglycemia can occur when these agents are combined with insulin or sulfonylureas. Notably, muscle cramps are not prominently featured among the listed adverse reactions in FDA labeling, leading many patients and clinicians to question whether there is a genuine association between GLP-1 therapy and musculoskeletal symptoms.

Muscle cramps are not listed as a common or characteristic adverse effect in the FDA-approved prescribing information for GLP-1 receptor agonists. A review of pivotal clinical trials for semaglutide (STEP, SUSTAIN), dulaglutide (REWIND), liraglutide (LEADER), and tirzepatide (SURPASS, SURMOUNT) does not identify muscle cramps as occurring at significantly higher rates compared to placebo groups. However, the absence of muscle cramps from official labeling does not definitively exclude the possibility of an association, as post-marketing surveillance and real-world clinical experience sometimes reveal adverse effects not detected in controlled trial settings.

Patient reports and clinical observations suggest that some individuals do experience muscle cramps while taking GLP-1 medications, though establishing direct causation remains challenging. These reports have increased alongside the dramatic rise in GLP-1 prescribing for weight management, where higher doses and more pronounced weight loss may contribute to metabolic changes that affect muscle function. It is important to distinguish between a direct pharmacologic effect of the medication and indirect consequences of the physiologic changes these drugs produce.

Based on current understanding, there is no established mechanism by which GLP-1 receptor agonism would directly cause muscle cramping. The GLP-1 receptor is expressed primarily in pancreatic beta cells, the gastrointestinal tract, and certain areas of the central nervous system, with limited expression in skeletal muscle tissue. Therefore, any relationship between GLP-1 therapy and muscle cramps is more likely to be indirect, mediated through secondary metabolic, nutritional, or fluid balance alterations rather than through direct receptor-mediated effects on muscle tissue. Patients experiencing suspected adverse effects should report them to their healthcare provider and to the FDA MedWatch program.

Several plausible mechanisms may hypothetically explain why patients on GLP-1 therapy experience muscle cramps, even in the absence of a direct pharmacologic effect. The most significant factor is likely related to rapid weight loss and associated nutritional changes. GLP-1 medications can produce substantial caloric restriction through appetite suppression and early satiety, leading to weight loss that may exceed 15-20% of body weight over several months with higher doses of semaglutide 2.4 mg or tirzepatide. Clinical trial data show that while fat mass accounts for the majority of weight loss, some lean mass reduction also occurs, which could potentially affect muscle function.

Electrolyte disturbances represent another important consideration. The gastrointestinal side effects of GLP-1 agents—particularly vomiting and diarrhea—can lead to depletion of essential electrolytes including sodium, magnesium, potassium, and calcium, all of which are critical for normal muscle contraction and relaxation. Magnesium deficiency, in particular, is a well-established cause of muscle cramps and may go unrecognized in patients experiencing chronic gastrointestinal symptoms. Additionally, reduced food intake may result in inadequate dietary intake of these minerals.

Dehydration is a related concern, as both reduced fluid intake (due to appetite suppression) and increased fluid losses (from gastrointestinal side effects) can contribute to volume depletion. Dehydration affects muscle perfusion and electrolyte balance, creating conditions favorable for cramping. This risk may be compounded by concomitant medications such as diuretics or SGLT2 inhibitors. Furthermore, patients losing significant weight may increase physical activity levels, potentially exceeding their current conditioning and leading to exercise-associated muscle cramps. Protein malnutrition, though less common, may occur in patients with severe appetite suppression or food aversions, potentially compromising muscle health and function over time.

Patients experiencing muscle cramps while taking GLP-1 medications should ensure adequate hydration based on individual needs. Rather than a fixed target, patients should monitor urine color (pale yellow indicates adequate hydration) and drink according to thirst, with increased intake during hot weather or physical activity. Most adults need approximately 2-3 liters (about 8-12 cups) of total water daily from all sources, though this varies based on body size, activity level, and medical conditions. Patients with heart failure, kidney disease, or other conditions requiring fluid restriction should follow their healthcare provider's specific guidance.

Nutritional optimization is essential for patients on GLP-1 therapy, particularly those experiencing significant weight loss. Despite reduced appetite, patients should prioritize protein intake (0.8-1.0 grams per kilogram of body weight daily, or approximately 0.36-0.45 grams per pound). Higher protein intake (1.0-1.2 g/kg for older adults and 1.2-1.6 g/kg for those engaging in resistance training) may help preserve lean muscle mass. A balanced diet rich in magnesium (leafy greens, nuts, whole grains), potassium (bananas, potatoes, beans), and calcium (dairy products, fortified alternatives) can help maintain electrolyte balance. Supplementation should generally be reserved for documented deficiencies, as excessive supplementation can cause side effects.

Gentle stretching exercises, particularly before bedtime and before physical activity, can reduce the frequency and severity of muscle cramps. Focus should be placed on major muscle groups prone to cramping, including the calves, quadriceps, and hamstrings. Gradual progression of exercise intensity is important for patients increasing physical activity during weight loss, allowing muscles to adapt appropriately. If cramps occur during exercise, immediate stretching of the affected muscle and gentle massage may provide relief. Quinine should not be used for leg cramps due to FDA safety concerns.

For persistent symptoms despite conservative measures, healthcare providers may consider checking serum electrolytes, magnesium, and possibly vitamin D levels, though evidence for vitamin D's role in muscle cramps is limited. A medication review should be conducted to identify drugs that might contribute to cramping (statins, diuretics). In some cases, temporary dose reduction or pausing dose escalation of the GLP-1 medication may be appropriate while nutritional status is optimized, though this decision should be made collaboratively between patient and provider.

While occasional mild muscle cramps may not require immediate medical attention, certain features warrant prompt evaluation by a healthcare provider. Patients should contact their physician if muscle cramps are severe, frequent (occurring daily or multiple times per day), or significantly impacting quality of life and daily activities. Cramps that persist for prolonged periods or do not respond to stretching and conservative measures also merit clinical assessment.

Muscle symptoms accompanied by other concerning features require more urgent evaluation. These include muscle weakness (difficulty climbing stairs, rising from a chair, or lifting objects), persistent muscle pain or tenderness, visible muscle swelling or changes in muscle appearance, or dark-colored urine, which may indicate rhabdomyolysis—a rare but serious condition involving muscle breakdown. Patients with dark/brown urine and severe muscle pain should seek emergency care immediately.

Patients experiencing severe dehydration symptoms (dizziness, decreased urination, confusion) or signs of significant electrolyte disturbance (irregular heartbeat, severe fatigue, numbness or tingling) should seek prompt medical care. Additionally, symptoms that could indicate pancreatitis (severe abdominal pain radiating to the back, persistent vomiting) or gallbladder disease (right upper quadrant pain, fever, jaundice) require urgent evaluation, as these are known potential complications of GLP-1 therapy.

Healthcare providers should conduct a thorough evaluation of patients reporting muscle cramps on GLP-1 therapy. This assessment should include a detailed history of symptom onset, frequency, severity, and relationship to medication initiation or dose changes. Physical examination should assess hydration status, muscle strength, and signs of nutritional deficiency. Laboratory investigation typically includes comprehensive metabolic panel, magnesium level, creatine kinase (if muscle injury is suspected), and possibly vitamin D level. Thyroid function testing may be appropriate, as hypothyroidism can cause muscle symptoms and may coexist with metabolic conditions.

In most cases, muscle cramps associated with GLP-1 therapy can be managed successfully with hydration, nutritional optimization, and supportive care, allowing patients to continue benefiting from these medications. Suspected adverse events should be reported to the FDA MedWatch program to improve post-marketing surveillance.

Muscle cramps are not listed as a common side effect in FDA labeling for GLP-1 receptor agonists, and clinical trials have not shown significantly higher rates compared to placebo. However, some patients report cramping, likely due to indirect factors such as electrolyte disturbances or rapid weight loss rather than direct drug effects.

Muscle cramps during GLP-1 therapy are typically caused by indirect factors including electrolyte depletion (especially magnesium and potassium) from gastrointestinal side effects, dehydration from reduced fluid intake or vomiting/diarrhea, rapid weight loss with some lean mass reduction, and increased physical activity exceeding current conditioning levels.

Contact your healthcare provider if muscle cramps are severe, frequent (daily or multiple times daily), or accompanied by muscle weakness, persistent pain, visible swelling, or dark-colored urine. Seek emergency care immediately if you experience dark/brown urine with severe muscle pain, as this may indicate rhabdomyolysis, a serious condition requiring urgent treatment.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.