LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

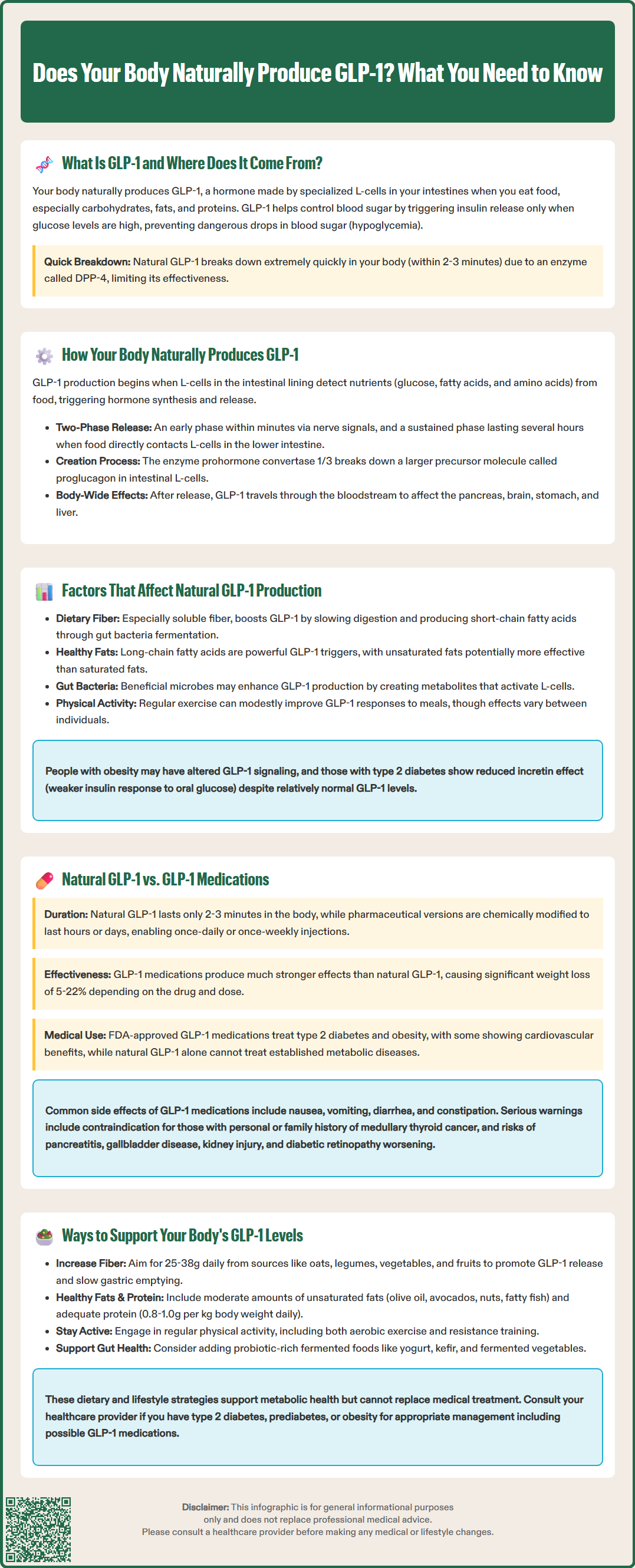

Does your body naturally produce GLP-1? Yes, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) is a hormone your body produces naturally in response to eating. Secreted by specialized L-cells in your intestines, GLP-1 plays a vital role in regulating blood sugar levels, stimulating insulin release, and controlling appetite. While your body's natural GLP-1 has a short lifespan of just 2 to 3 minutes before being broken down, it performs essential metabolic functions that help maintain glucose homeostasis. Understanding how your body produces and uses GLP-1 provides important context for both normal metabolism and the development of GLP-1-based medications used to treat type 2 diabetes and obesity.

Quick Answer: Yes, your body naturally produces GLP-1, a hormone secreted by intestinal L-cells in response to food intake that regulates blood sugar and appetite.

We offer compounded medications and Zepbound®. Compounded medications are prepared by licensed pharmacies and are not FDA-approved. References to Wegovy®, Ozempic®, Rybelsus®, Mounjaro®, or Saxenda®, or other GLP-1 brands, are informational only. Compounded and FDA-approved medications are not interchangeable.

Yes, your body naturally produces glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), a hormone that plays a crucial role in regulating blood sugar levels and appetite. GLP-1 belongs to a class of hormones called incretins, which are released by the intestines in response to food intake.

GLP-1 is primarily synthesized and secreted by specialized enteroendocrine cells called L-cells, which are located throughout the intestinal tract but are most concentrated in the distal small intestine (ileum) and colon. When you eat, nutrients—particularly carbohydrates, fats, and proteins—stimulate these L-cells to release GLP-1 into the bloodstream.

Once released, GLP-1 performs several important metabolic functions. It stimulates insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells in a glucose-dependent manner, meaning it only promotes insulin release when blood sugar levels are elevated. This mechanism helps prevent hypoglycemia. Additionally, GLP-1 suppresses glucagon secretion from pancreatic alpha cells, slows gastric emptying to moderate the rate at which nutrients enter the bloodstream, and acts on the brain to promote satiety and reduce appetite.

The active forms of endogenous GLP-1 are primarily GLP-1(7-36) amide and, to a lesser extent, GLP-1(7-37). However, naturally produced GLP-1 has a very short half-life—approximately 2 to 3 minutes—because it is rapidly degraded by the enzyme dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4). This brief duration of action is why pharmaceutical companies developed longer-acting GLP-1 receptor agonists for therapeutic use. Understanding your body's natural GLP-1 production provides important context for both metabolic health and the development of GLP-1-based medications.

The production of GLP-1 is a sophisticated physiological process that begins the moment food enters your digestive system. L-cells in the intestinal lining contain specialized receptors that detect nutrients, particularly glucose, fatty acids, and amino acids. When these nutrients make contact with L-cells, they trigger a cascade of cellular signals that result in GLP-1 synthesis and secretion.

The process occurs in two distinct phases. The early phase begins within minutes of eating, when nutrients in the upper gastrointestinal tract trigger neural and hormonal signals that stimulate L-cells even before food reaches the distal intestine. This anticipatory response is mediated by vagal nerve activity and other gut hormones. The second, more sustained phase occurs when nutrients directly contact L-cells in the lower small intestine and colon, producing a more prolonged GLP-1 release that continues for several hours after a meal.

GLP-1 is derived from a larger precursor molecule called proglucagon through post-translational processing. In the intestinal L-cells, proglucagon is cleaved by the enzyme prohormone convertase 1/3 to produce GLP-1, along with other peptides including GLP-2 and glicentin. The same proglucagon gene is expressed in pancreatic alpha cells, but different enzymatic processing in those cells produces glucagon instead of GLP-1.

Once secreted into the bloodstream, GLP-1 travels to target tissues including the pancreas, brain, and stomach. It also affects liver function, though primarily through indirect mechanisms involving insulin, glucagon, and neural pathways rather than direct hepatic action. Once in circulation, GLP-1 is rapidly degraded by DPP-4, which cleaves the active hormone to form GLP-1(9-36) with significantly reduced insulinotropic activity. This rapid turnover means that maintaining therapeutic levels of GLP-1 activity requires either continuous endogenous production or pharmaceutical intervention with DPP-4-resistant analogs.

Several physiological and lifestyle factors influence your body's natural GLP-1 production and secretion. Understanding these factors can help explain individual variations in metabolic health and glucose regulation.

Dietary composition is one of the most important determinants of GLP-1 release. Different macronutrients stimulate GLP-1 secretion to varying degrees:

Fiber and complex carbohydrates: Dietary fiber, particularly soluble fiber, enhances GLP-1 secretion by slowing nutrient absorption and allowing more prolonged contact with L-cells in the distal intestine. Fermentation of fiber by gut bacteria also produces short-chain fatty acids that directly stimulate L-cells.

Fats: Fatty acids are potent stimulators of GLP-1 release, with long-chain fatty acids being particularly effective. Some studies suggest that unsaturated fats may promote greater GLP-1 secretion than saturated fats, though more research is needed.

Proteins: Protein intake stimulates moderate GLP-1 release, with certain amino acids being more effective than others.

Body weight and metabolic health also affect GLP-1 dynamics. Some studies suggest that individuals with obesity may have alterations in GLP-1 signaling, though findings are heterogeneous. In type 2 diabetes, the incretin effect (the enhanced insulin response to oral versus intravenous glucose) is reduced. GLP-1 secretion may be normal or modestly reduced in type 2 diabetes, with considerable variability across studies.

Gut microbiome composition may influence GLP-1 production, though evidence in humans remains preliminary. Some beneficial bacteria produce metabolites that may stimulate L-cells. Additionally, physical activity has been associated with modest enhancements in GLP-1 responses to meals in some studies, though the effects are variable. Age-related changes in intestinal function may also affect GLP-1 production, though evidence remains limited.

While your body's natural GLP-1 and pharmaceutical GLP-1 receptor agonists share the same basic mechanism of action, there are important differences in their structure, duration of effect, and clinical applications.

Structural and pharmacological differences are fundamental. Natural human GLP-1 exists primarily as GLP-1(7-36) amide, a peptide that is rapidly degraded by DPP-4, resulting in a half-life of only 2 to 3 minutes. In contrast, GLP-1 receptor agonists approved by the FDA—including semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy), dulaglutide (Trulicity), liraglutide (Victoza, Saxenda), and tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Zepbound, which also activates GIP receptors)—are modified to resist DPP-4 degradation. These modifications extend their half-lives from hours to days, allowing once-daily or once-weekly dosing.

The magnitude of effect differs substantially. Pharmaceutical GLP-1 agonists produce sustained receptor activation at levels far exceeding what natural GLP-1 achieves, even after meals. This prolonged, supraphysiological stimulation results in greater glucose-lowering effects, more pronounced appetite suppression, and clinically significant weight loss that varies by medication and dose: approximately 5-8% with liraglutide 3 mg, 10-15% with semaglutide 2.4 mg, and 15-22% with tirzepatide at higher doses. Natural GLP-1 produces more modest, meal-related effects that are part of normal metabolic regulation.

Clinical applications reflect these differences. GLP-1 medications are FDA-approved for type 2 diabetes management and, at higher doses, for chronic weight management in adults with obesity or overweight with weight-related comorbidities. Specific agents (liraglutide, semaglutide, dulaglutide) have demonstrated cardiovascular benefits in clinical trials. Natural GLP-1 production, while essential for normal glucose homeostasis, is insufficient to treat established metabolic disease.

Adverse effects also differ. While natural GLP-1 rarely causes problems, pharmaceutical GLP-1 agonists commonly cause gastrointestinal side effects including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation, particularly during dose escalation. These medications carry a boxed warning about thyroid C-cell tumors (contraindicated with personal/family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma or Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia syndrome type 2) and warnings about potential risks including pancreatitis, gallbladder disease, acute kidney injury with dehydration, and worsening diabetic retinopathy with rapid glucose reduction (particularly with semaglutide).

While you cannot dramatically increase natural GLP-1 production to therapeutic levels without medication, several evidence-based dietary and lifestyle strategies may optimize your body's endogenous GLP-1 response and support metabolic health.

Dietary approaches that may enhance GLP-1 secretion include:

Increase fiber intake: Consuming adequate dietary fiber daily (approximately 25g for women and 38g for men according to US Dietary Guidelines, though most Americans fall short) may promote GLP-1 release. Soluble fiber from sources like oats, legumes, vegetables, and fruits slows gastric emptying and allows nutrients to reach distal L-cells more effectively.

Include healthy fats: Incorporating moderate amounts of unsaturated fats from sources like olive oil, avocados, nuts, and fatty fish may support GLP-1 secretion, though evidence specifically comparing fat types is still emerging.

Consume adequate protein: Protein-rich foods stimulate GLP-1 release and promote satiety through complementary mechanisms. Aim for 0.8 to 1.0 grams per kilogram of body weight daily, distributed across meals. If you have kidney disease, consult your healthcare provider about appropriate protein intake.

Consider fermented foods: Some evidence suggests probiotic-rich foods like yogurt, kefir, and fermented vegetables may support a healthy gut microbiome, which could potentially influence GLP-1 production, though human studies are limited.

Lifestyle modifications that may support GLP-1 function include regular physical activity, which has been associated with modest improvements in postprandial GLP-1 responses in some studies. Both aerobic exercise and resistance training appear beneficial. Maintaining a healthy body weight through balanced nutrition and regular activity may help preserve normal GLP-1 secretion patterns.

Important considerations: These strategies support overall metabolic health but should not be viewed as substitutes for medical treatment when indicated. If you have type 2 diabetes, prediabetes, or obesity-related health conditions, consult your healthcare provider about appropriate management, which may include GLP-1 medications alongside lifestyle modifications. If you're taking GLP-1 medications, seek immediate medical attention for severe, persistent abdominal pain (possible pancreatitis), persistent vomiting with inability to keep fluids down, or yellowing of skin/eyes with right upper abdominal pain (possible gallbladder disease).

Natural GLP-1 has a very short half-life of approximately 2 to 3 minutes because it is rapidly broken down by the enzyme dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4). This brief duration is why pharmaceutical GLP-1 medications are modified to resist degradation and provide longer-lasting effects.

Yes, certain dietary strategies may enhance natural GLP-1 secretion, including consuming adequate fiber (25g for women, 38g for men daily), incorporating healthy fats, and eating sufficient protein. However, these dietary approaches produce modest effects and cannot replicate the therapeutic levels achieved by GLP-1 medications.

Natural GLP-1 is rapidly degraded within minutes and produces modest, meal-related metabolic effects. FDA-approved GLP-1 medications like semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy) are structurally modified to resist breakdown, have half-lives of days rather than minutes, and produce sustained receptor activation that results in greater glucose-lowering effects and clinically significant weight loss.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.