LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

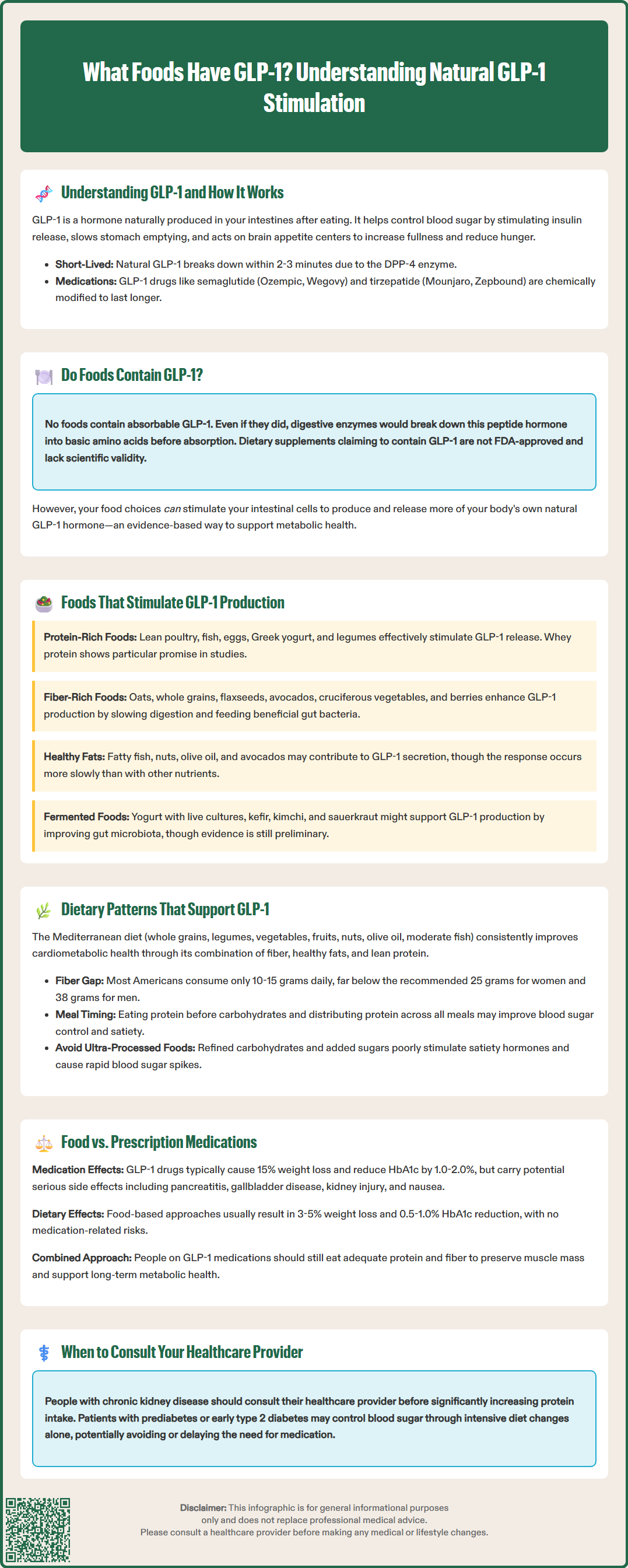

Many people wonder if they can obtain GLP-1 (glucagon-like peptide-1) directly from foods, especially given the popularity of GLP-1 medications like Ozempic and Wegovy for diabetes and weight management. The short answer is no—no foods contain absorbable GLP-1 hormone. However, certain foods can stimulate your body to produce more of its own GLP-1 naturally. Understanding how dietary choices influence your body's GLP-1 secretion provides an evidence-based approach to supporting metabolic health, though the effects differ substantially from prescription medications. This article explains what GLP-1 is, why you cannot get it from food, and which dietary strategies may enhance your body's natural production.

Quick Answer: No foods contain GLP-1 hormone, but protein-rich foods, dietary fiber, and healthy fats can stimulate your intestinal cells to produce more GLP-1 naturally.

We offer compounded medications and Zepbound®. Compounded medications are prepared by licensed pharmacies and are not FDA-approved. References to Wegovy®, Ozempic®, Rybelsus®, Mounjaro®, or Saxenda®, or other GLP-1 brands, are informational only. Compounded and FDA-approved medications are not interchangeable.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) is an incretin hormone produced naturally by specialized L-cells in your intestinal lining, primarily in the ileum and colon. When you eat, these cells release GLP-1 into your bloodstream in response to nutrient intake, particularly carbohydrates and fats. This hormone plays a crucial role in glucose metabolism and appetite regulation.

GLP-1 works through several complementary mechanisms. It stimulates insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells in a glucose-dependent manner, meaning it only triggers insulin release when blood glucose levels are elevated. Simultaneously, it suppresses glucagon secretion from pancreatic alpha cells, reducing hepatic glucose production. These actions help maintain blood glucose within normal ranges after meals.

Beyond glucose control, GLP-1 significantly affects satiety and gastric function. The hormone slows gastric emptying, prolonging the time food remains in your stomach and contributing to feelings of fullness, though this effect may diminish with chronic exposure. It also acts on appetite centers in the hypothalamus, reducing hunger signals and food intake. These effects explain why medications targeting the GLP-1 pathway have proven effective for both type 2 diabetes management and weight loss.

These medications include GLP-1 receptor agonists like semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy, Rybelsus) and liraglutide, as well as dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonists like tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Zepbound). Another medication class, DPP-4 inhibitors, works by preventing the breakdown of your body's natural GLP-1, though with more modest effects.

Naturally produced GLP-1 has a very short half-life of approximately 2-3 minutes. The enzyme dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) rapidly degrades circulating GLP-1, which is why pharmaceutical versions are chemically modified to resist this breakdown and maintain therapeutic levels for extended periods.

No foods contain biologically active GLP-1 hormone that your body can absorb and utilize. GLP-1 is a peptide hormone synthesized exclusively within your own intestinal cells—it is not present in plant or animal food sources in a form that would survive digestion and enter your circulation.

This is an important distinction that often causes confusion. Even if a food theoretically contained GLP-1 (which none do), peptide hormones are proteins that would be broken down into individual amino acids by digestive enzymes in your stomach and small intestine. These amino acids would then be absorbed as basic building blocks, not as intact, functional hormones. The digestive process is specifically designed to dismantle proteins into their component parts.

The concept differs fundamentally from how prescription GLP-1 receptor agonists work. Most GLP-1 medications like semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy) and liraglutide are administered by subcutaneous injection, bypassing the digestive system entirely. One exception is oral semaglutide (Rybelsus), which uses a special absorption enhancer to protect the molecule from digestive enzymes. These synthetic analogs are also chemically modified to resist enzymatic degradation, allowing them to remain active in your bloodstream for hours to days rather than minutes.

Consumers should be wary of dietary supplements claiming to contain GLP-1 or promising "GLP-1-like" effects, as these claims are not FDA-approved and lack scientific validity.

While you cannot obtain GLP-1 directly from food, your dietary choices profoundly influence how much GLP-1 your own intestinal cells produce and release. This endogenous production represents the primary way nutrition affects your GLP-1 levels. Understanding which foods and eating patterns stimulate your body's natural GLP-1 secretion provides an evidence-based approach to supporting metabolic health through diet, though the magnitude of effect differs substantially from pharmaceutical interventions.

Certain nutrients and food components can trigger GLP-1 secretion from your intestinal L-cells. Protein-rich foods can effectively stimulate GLP-1 release, with some studies suggesting whey protein may be particularly beneficial. High-quality protein sources include:

Lean poultry (chicken, turkey)

Fish and seafood (salmon, cod, shrimp)

Eggs and egg whites

Greek yogurt and cottage cheese

Legumes (lentils, chickpeas, black beans)

Lean cuts of beef and pork

Note: Individuals with chronic kidney disease should consult their healthcare provider before significantly increasing protein intake.

Dietary fiber, particularly soluble and fermentable types, can enhance GLP-1 production through multiple mechanisms. Fiber slows gastric emptying and provides substrate for beneficial gut bacteria, which produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that may stimulate L-cells. Excellent fiber sources include:

Oats and oat bran

Barley and whole grains

Flaxseeds and chia seeds

Avocados

Brussels sprouts, broccoli, and leafy greens

Berries (raspberries, blackberries)

Apples and pears with skin

Resistant starch sources (cooled potatoes, green bananas)

Healthy fats may also contribute to GLP-1 secretion, though the response may be somewhat delayed compared to other nutrients. Sources include fatty fish, nuts (almonds, walnuts), olive oil, and avocados.

Fermented foods containing probiotics might support GLP-1 production by influencing gut microbiota, though evidence remains preliminary. Options include yogurt with live cultures, kefir, kimchi, and sauerkraut. The gut microbiome's role in GLP-1 regulation is an active area of research, with emerging evidence suggesting that microbial diversity and specific bacterial strains may influence incretin hormone secretion, but more human studies are needed to establish clinical significance.

Beyond individual foods, overall dietary patterns may influence metabolic health and potentially GLP-1 function. The Mediterranean diet has demonstrated consistent benefits for cardiometabolic health in clinical studies. This pattern emphasizes whole grains, legumes, vegetables, fruits, nuts, olive oil, and moderate fish intake while limiting processed foods and red meat. The combination of fiber, healthy fats, and lean protein creates multiple opportunities for nutrient-stimulated hormone responses throughout the day.

Meal composition and timing may affect postprandial metabolism. Some studies suggest that consuming protein before carbohydrates might improve postprandial (after-meal) glucose control and satiety, though the specific impact on GLP-1 levels requires further research. Distributing protein intake across meals rather than concentrating it at dinner appears beneficial for overall metabolic health.

Adequate fiber intake supports digestive and metabolic health. The U.S. Dietary Guidelines recommend approximately 14 grams of fiber per 1,000 calories consumed, which translates to about 25 grams daily for women and 38 grams for men, with somewhat lower targets for older adults. However, most Americans consume only 10-15 grams daily, representing a significant opportunity for dietary improvement. Gradually increasing fiber intake while maintaining adequate hydration helps prevent gastrointestinal discomfort during the transition.

Emerging research suggests that time-restricted eating patterns may influence metabolic health, though evidence remains preliminary. Some studies indicate that aligning eating windows with circadian rhythms could affect hormone responses, but this area requires further investigation before specific recommendations can be made. Patients taking insulin or sulfonylureas should consult their healthcare provider before changing meal timing, as these medications increase hypoglycemia risk.

Minimizing ultra-processed foods appears important for maintaining overall metabolic health. Highly processed foods often contain refined carbohydrates, added sugars, and minimal fiber—a combination that may provide poor stimulation of satiety hormones while promoting rapid glucose spikes. Whole food sources consistently demonstrate superior effects on satiety and glycemic control compared to processed alternatives with similar macronutrient profiles.

The magnitude of GLP-1 enhancement achievable through diet differs substantially from pharmaceutical interventions, and patients should understand these distinctions clearly. Prescription GLP-1 receptor agonists produce sustained, supraphysiologic levels of GLP-1 activity—far exceeding what dietary modifications can achieve. Medications maintain therapeutic drug levels continuously, whereas food-stimulated GLP-1 secretion occurs in pulses after meals and is rapidly degraded.

Clinical trial data illustrate this difference. GLP-1 receptor agonists typically produce weight reduction and HbA1c decreases that vary by medication and dose. For example, semaglutide 2.4 mg (Wegovy) yields approximately 15% body weight reduction in clinical trials, while lower doses used for diabetes (Ozempic) produce more modest weight loss. Tirzepatide, a dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist (Mounjaro, Zepbound), has demonstrated even greater weight loss in clinical trials. For glycemic control, these medications typically reduce HbA1c by 1.0-2.0% in patients with type 2 diabetes.

While dietary interventions emphasizing protein, fiber, and whole foods can improve metabolic parameters and support weight management, the effects are generally more modest—typically 3-5% weight loss and HbA1c reductions of 0.5-1.0% when implemented without other interventions, as seen in programs like the Diabetes Prevention Program.

However, dietary approaches offer distinct advantages. They carry no risk of medication-specific adverse effects such as nausea, vomiting, or rare but serious complications. GLP-1 medications carry FDA warnings about potential risks including pancreatitis, gallbladder disease, and acute kidney injury with dehydration. They also have a boxed warning regarding thyroid C-cell tumors observed in rodents (though human relevance remains uncertain). Patients should seek immediate medical attention for severe, persistent abdominal pain while taking these medications, as this could indicate pancreatitis.

The optimal approach for many patients involves combining strategies. Individuals taking GLP-1 receptor agonists should still prioritize protein and fiber intake to maintain muscle mass during weight loss and support long-term metabolic health. Conversely, patients with prediabetes or early type 2 diabetes may achieve adequate glycemic control through intensive dietary modification, potentially delaying or avoiding medication initiation.

Patients considering GLP-1 medications should consult their healthcare provider to discuss whether pharmaceutical intervention is appropriate for their specific clinical situation, including consideration of cardiovascular risk factors, degree of hyperglycemia, and previous response to lifestyle interventions. Dietary optimization remains foundational regardless of medication use.

No, you cannot obtain GLP-1 directly from foods. GLP-1 is a peptide hormone produced only by your intestinal cells, and even if foods contained it, digestive enzymes would break it down into amino acids before absorption. However, certain foods can stimulate your body to produce more GLP-1 naturally.

Protein-rich foods (especially whey protein, lean poultry, fish, eggs, and legumes), high-fiber foods (oats, whole grains, vegetables, berries), and healthy fats (fatty fish, nuts, olive oil, avocados) can trigger GLP-1 secretion from intestinal L-cells. Fermented foods with probiotics may also support GLP-1 production through gut microbiome effects.

Dietary approaches produce much more modest effects than prescription GLP-1 medications. While medications maintain sustained, supraphysiologic hormone levels and typically produce significant weight reduction and HbA1c decreases, food-stimulated GLP-1 is released in brief pulses after meals and rapidly degraded within minutes, resulting in smaller metabolic improvements.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.