LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

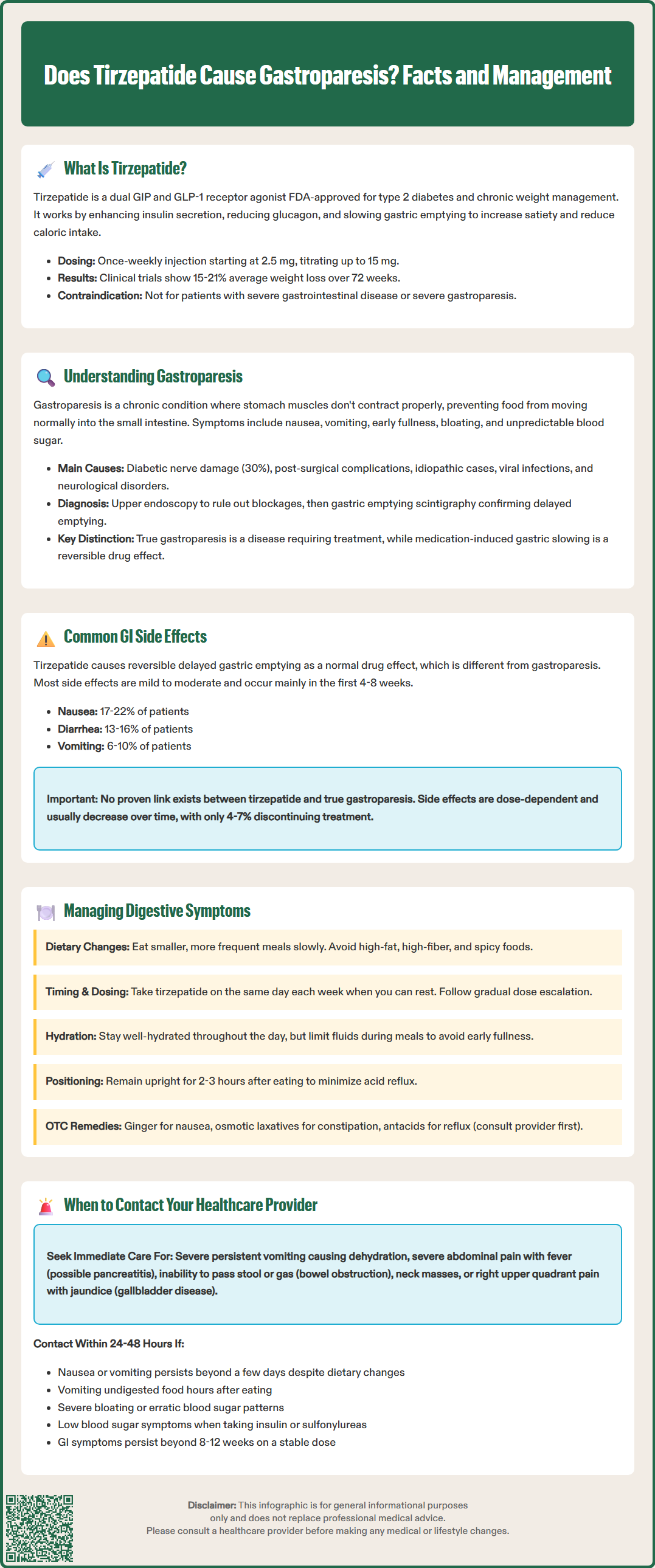

Tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Zepbound) is an FDA-approved dual GIP and GLP-1 receptor agonist used for type 2 diabetes and chronic weight management. A common concern among patients and clinicians is whether tirzepatide causes gastroparesis—a chronic condition of impaired gastric emptying. While tirzepatide therapeutically slows gastric emptying as part of its mechanism of action, this pharmacological effect differs fundamentally from gastroparesis as a disease state. Understanding this distinction, along with recognizing gastrointestinal side effects and knowing when symptoms require medical evaluation, is essential for safe and effective tirzepatide therapy.

Quick Answer: Tirzepatide causes therapeutic, reversible slowing of gastric emptying but has not been established to cause gastroparesis as a pathological condition.

Tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Zepbound) is a dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist approved by the FDA for type 2 diabetes management and chronic weight management in adults with obesity or overweight with weight-related comorbidities.

The medication works through multiple complementary mechanisms. By activating GIP receptors, tirzepatide enhances insulin secretion while reducing glucagon levels. Simultaneously, GLP-1 receptor activation stimulates glucose-dependent insulin release, suppresses inappropriate glucagon secretion, and slows gastric emptying. This delayed gastric emptying contributes to increased satiety and reduced caloric intake, supporting both glycemic control and weight loss.

Tirzepatide is administered as a once-weekly subcutaneous injection, with doses starting at 2.5 mg for initiation and titrating up to 15 mg depending on therapeutic goals and tolerability. In the SURPASS-2 trial, tirzepatide demonstrated greater efficacy compared to semaglutide 1 mg, with patients achieving substantial improvements in HbA1c reduction. In the SURMOUNT-1 trial, patients with obesity achieved average weight reductions of approximately 15-21% of body weight over 72 weeks, alongside improvements in cardiovascular risk factors including blood pressure and lipid profiles, though cardiovascular outcome benefits have not yet been established.

Understanding tirzepatide's mechanism of action—particularly its effect on gastric emptying—is essential when evaluating its gastrointestinal side effect profile. Importantly, tirzepatide is not recommended for use in patients with severe gastrointestinal disease, including severe gastroparesis. Additionally, the delayed gastric emptying can affect the absorption of oral medications, particularly oral contraceptives, which may require additional contraceptive measures.

Gastroparesis is a chronic medical condition characterized by delayed gastric emptying in the absence of mechanical obstruction. The stomach's normal muscular contractions become impaired, preventing proper movement of food from the stomach into the small intestine. This dysfunction can significantly impact nutritional status, glycemic control in people with diabetes, and overall quality of life.

Common symptoms of gastroparesis include persistent nausea, vomiting (particularly of undigested food), early satiety, postprandial fullness, bloating, and upper abdominal pain. Patients may also experience weight loss, poor appetite, and gastroesophageal reflux. In individuals with diabetes, gastroparesis can cause erratic blood glucose levels due to unpredictable nutrient absorption, making diabetes management particularly challenging.

The most common causes of gastroparesis include diabetic neuropathy (accounting for approximately 30% of cases), post-surgical complications (particularly after gastric or esophageal surgery), and idiopathic gastroparesis where no clear cause is identified. In many US cohorts, idiopathic gastroparesis is the most common form. Other etiologies include viral infections, neurological disorders such as Parkinson's disease, connective tissue diseases like scleroderma, and certain medications that affect gastric motility.

Diagnosis typically requires ruling out mechanical obstruction (often via upper endoscopy) followed by gastric emptying scintigraphy, where patients consume a standardized radiolabeled meal and imaging tracks food movement through the digestive system. According to American College of Gastroenterology guidelines, retention of more than 10% of the meal at four hours confirms delayed gastric emptying. It is important to distinguish true gastroparesis—a pathological condition requiring specific treatment—from the therapeutic, reversible slowing of gastric emptying caused by medications like tirzepatide, which represents a pharmacological effect rather than a disease state.

Gastrointestinal side effects represent the most commonly reported adverse events with tirzepatide therapy, occurring in a substantial proportion of patients during clinical trials. The SURPASS clinical trial program demonstrated that nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, constipation, dyspepsia, and abdominal pain are the predominant GI complaints. These effects are generally dose-dependent, typically mild to moderate in severity, and most pronounced during dose initiation or escalation.

In the pivotal SURPASS-2 trial, nausea occurred in 17-22% of patients on tirzepatide (varying by dose) compared to 18% on semaglutide 1 mg. Diarrhea affected 13-16% of tirzepatide users, while vomiting occurred in 6-10% of patients. Most gastrointestinal adverse events emerged within the first 4-8 weeks of treatment and diminished over time as patients developed tolerance. Discontinuation rates due to GI side effects ranged from 4-7% across tirzepatide doses in these clinical trials.

The delayed gastric emptying induced by tirzepatide is a pharmacological effect, not gastroparesis. This distinction is clinically important: tirzepatide causes a controlled, reversible slowing of gastric emptying that contributes to its therapeutic benefits, whereas gastroparesis is a pathological condition with impaired gastric motility that persists independent of medication use.

Causality between tirzepatide and true gastroparesis has not been established, though rare severe GI motility events have been reported with GLP-1 receptor agonists in postmarketing surveillance. Patients with pre-existing gastroparesis or severe gastrointestinal disease were excluded from major clinical trials, and the FDA label specifically states that tirzepatide is not recommended in patients with severe gastrointestinal disease, including severe gastroparesis. Clinicians should carefully evaluate patients with persistent, severe upper GI symptoms to differentiate expected medication effects from other underlying conditions.

Effective management of gastrointestinal symptoms can significantly improve treatment adherence and patient satisfaction with tirzepatide therapy. Product labeling and clinical experience suggest several strategies to minimize GI side effects while maintaining therapeutic benefits.

Dietary modifications form the cornerstone of symptom management. Patients should consume smaller, more frequent meals rather than large portions, which can overwhelm the slower gastric emptying. Eating slowly and chewing food thoroughly aids digestion. Avoiding high-fat, high-fiber, and spicy foods can reduce nausea and bloating, as these foods delay gastric emptying further. Staying well-hydrated throughout the day helps prevent constipation, though patients should limit fluid intake during meals to avoid early satiety. Remaining upright for 2-3 hours after eating can minimize reflux symptoms.

Medication timing and dosing strategies also play important roles. Taking tirzepatide on the same day each week, preferably when patients can rest if nausea occurs, improves tolerability. The gradual dose escalation schedule (starting at 2.5 mg and increasing every 4 weeks) allows the GI system to adapt. Some patients may benefit from slower titration schedules, but any changes to the recommended dose escalation should be directed by the prescribing healthcare provider.

Symptomatic treatment may include over-the-counter remedies for mild symptoms. Ginger supplements or ginger tea may help with nausea, though evidence is limited. For constipation, osmotic laxatives like polyethylene glycol are generally preferred; fiber supplements should be used cautiously as they may worsen bloating in patients with delayed gastric emptying. Antacids or H2-receptor antagonists can address reflux symptoms. Patients should consult their healthcare provider before starting any new medications, as some treatments may mask symptoms requiring medical evaluation.

Patients should maintain open communication with their healthcare team about symptom severity and impact on daily functioning. Any dose adjustments should be made under healthcare provider supervision. These practical strategies enable most patients to continue benefiting from tirzepatide while minimizing gastrointestinal discomfort.

While mild gastrointestinal symptoms are expected with tirzepatide, certain warning signs require prompt medical evaluation to distinguish normal medication effects from serious complications or underlying conditions requiring intervention.

Seek immediate medical attention for severe, persistent vomiting that prevents adequate fluid or medication intake, as this can lead to dehydration and electrolyte imbalances. Signs of dehydration include decreased urination, dark urine, dizziness, rapid heartbeat, and extreme thirst. Severe abdominal pain, particularly if accompanied by fever, could indicate pancreatitis—a rare but serious adverse effect associated with GLP-1 receptor agonists. Progressive abdominal distension, persistent vomiting, or inability to pass stool or gas may indicate bowel obstruction requiring urgent care. The FDA label includes a boxed warning about thyroid C-cell tumors observed in animal studies, so any neck mass or difficulty swallowing warrants evaluation. Symptoms of gallbladder disease, including right upper quadrant pain, jaundice, or clay-colored stools, require assessment, as rapid weight loss increases cholelithiasis risk.

Contact your healthcare provider within 24-48 hours if you experience persistent nausea or vomiting lasting more than a few days despite dietary modifications, as this may indicate inadequate tolerance requiring dose adjustment. Unintentional weight loss exceeding expected therapeutic goals or inability to maintain adequate nutrition necessitates evaluation. New or worsening symptoms of gastroparesis—including vomiting undigested food hours after eating, severe bloating, or erratic blood glucose patterns in diabetes patients—should be assessed to determine whether symptoms represent medication effects or underlying pathology. Patients taking insulin or sulfonylureas should be particularly vigilant about hypoglycemia risk if nausea or vomiting reduces food intake.

Routine follow-up should address ongoing GI symptoms affecting quality of life, even if not severe. Patients experiencing persistent symptoms beyond 8-12 weeks of stable dosing may benefit from additional evaluation or treatment modifications. Those with pre-existing gastrointestinal conditions should maintain closer monitoring, as tirzepatide's effects on gastric emptying may exacerbate underlying disorders.

Healthcare providers can perform appropriate investigations, including gastric emptying studies if true gastroparesis is suspected, adjust medication regimens, provide prescription antiemetics if needed, or consider alternative therapeutic options. Per the FDA label, tirzepatide is not recommended in patients with severe gastrointestinal disease, including severe gastroparesis, and persistent severe symptoms warrant reassessment or discontinuation. Patient safety depends on distinguishing expected, manageable side effects from complications requiring medical intervention, making open communication with healthcare providers essential throughout tirzepatide therapy.

Tirzepatide causes a controlled, reversible slowing of gastric emptying as a therapeutic mechanism, while gastroparesis is a pathological condition with persistently impaired gastric motility independent of medication use. The medication effect is intentional and contributes to weight loss and glycemic control, whereas gastroparesis is a disease requiring specific treatment.

In clinical trials, nausea occurred in 17-22% of patients, diarrhea in 13-16%, and vomiting in 6-10%. These effects are typically mild to moderate, most pronounced during dose initiation or escalation, and generally diminish over time as tolerance develops.

Seek immediate care for severe persistent vomiting, signs of dehydration, severe abdominal pain, or inability to pass stool. Contact your provider within 24-48 hours for persistent nausea lasting more than a few days, vomiting undigested food hours after eating, or symptoms affecting your ability to maintain adequate nutrition.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.