LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

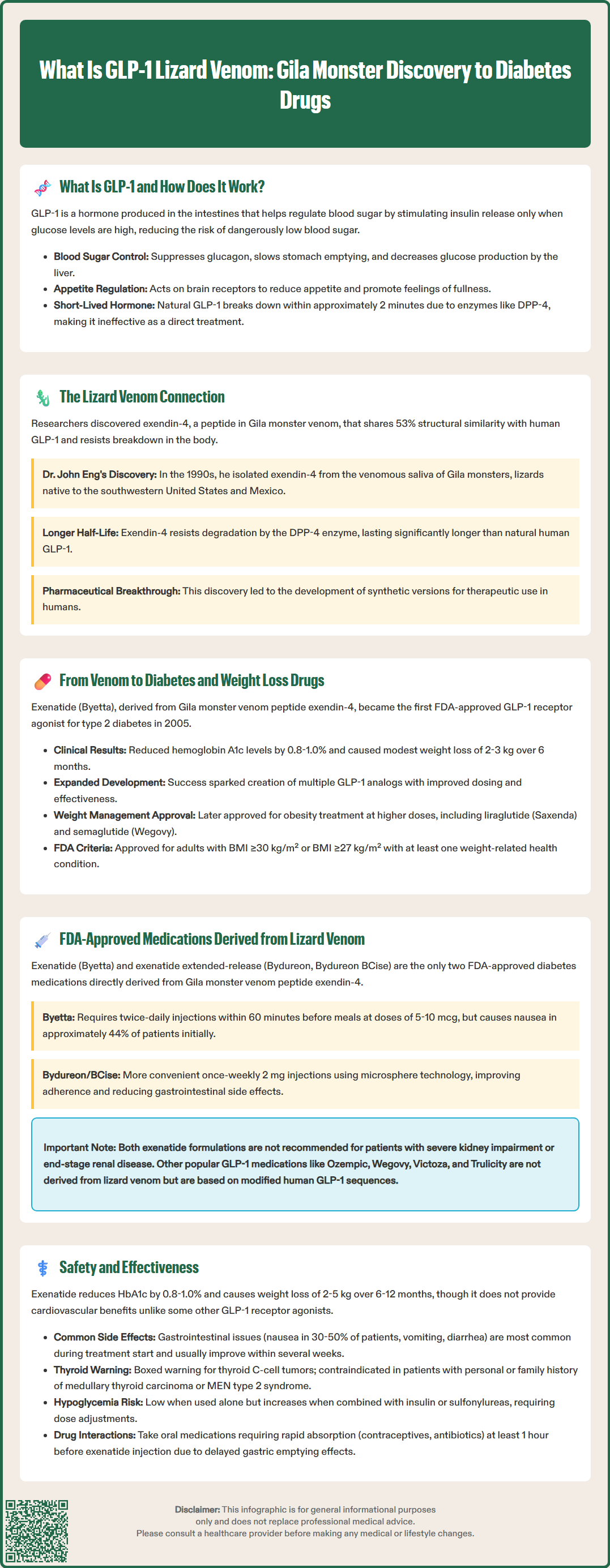

GLP-1 medications represent a breakthrough in diabetes and obesity treatment, with an unexpected origin: Gila monster venom. In the 1990s, researchers discovered exendin-4, a peptide in the venomous saliva of this southwestern lizard, which mimics human GLP-1 hormone but resists rapid breakdown. This discovery led to the development of exenatide (Byetta), the first FDA-approved GLP-1 receptor agonist in 2005. Today, GLP-1 drugs improve blood sugar control and promote weight loss, transforming metabolic disease management. Understanding the lizard venom connection provides insight into how nature-inspired pharmaceutical innovation continues to advance clinical care.

Quick Answer: GLP-1 medications originated from exendin-4, a peptide discovered in Gila monster venom that mimics human GLP-1 hormone with enhanced stability, leading to FDA-approved diabetes treatments.

We offer compounded medications and Zepbound®. Compounded medications are prepared by licensed pharmacies and are not FDA-approved. References to Wegovy®, Ozempic®, Rybelsus®, Mounjaro®, or Saxenda®, or other GLP-1 brands, are informational only. Compounded and FDA-approved medications are not interchangeable.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) is a naturally occurring hormone produced in the intestinal L-cells of the human gastrointestinal tract. This incretin hormone plays a critical role in glucose homeostasis and metabolic regulation. When food enters the digestive system, GLP-1 is released into the bloodstream, where it exerts multiple physiological effects that help maintain normal blood sugar levels.

The primary mechanism of action involves stimulating glucose-dependent insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells. This means GLP-1 promotes insulin release only when blood glucose levels are elevated, reducing the risk of hypoglycemia compared to some other diabetes medications. Additionally, GLP-1 suppresses glucagon secretion from pancreatic alpha cells, which decreases hepatic glucose production. The hormone also slows gastric emptying, prolonging the time food remains in the stomach and moderating postprandial glucose excursions.

Beyond glycemic control, GLP-1 influences appetite regulation through central nervous system pathways. It acts on receptors in the hypothalamus and brainstem to promote satiety and reduce food intake. This dual action on both glucose metabolism and appetite has made GLP-1 a therapeutic target for type 2 diabetes and obesity management.

Native human GLP-1 has a very short half-life of approximately 2 minutes due to rapid degradation primarily by the enzyme dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4), with neutral endopeptidase (NEP) also contributing to its breakdown. This brief duration of action limits its therapeutic utility in its natural form, necessitating the development of longer-acting GLP-1 receptor agonists that can provide sustained clinical benefits with less frequent dosing.

The connection between lizard venom and GLP-1 medications represents one of the most remarkable examples of biomimicry in modern pharmacology. In the 1990s, researchers studying the Gila monster (Heloderma suspectum), a venomous lizard native to the southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico, made a groundbreaking discovery that would transform diabetes treatment.

Dr. John Eng, an endocrinologist at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in the Bronx, was investigating the biochemical composition of Gila monster venomous saliva when he isolated a peptide he named exendin-4. This 39-amino acid peptide showed structural similarity to human GLP-1, sharing approximately 53% sequence homology. Importantly, exendin-4 demonstrated resistance to DPP-4 degradation, giving it a significantly longer half-life than native human GLP-1.

The Gila monster feeds infrequently, sometimes going months between meals. Researchers have proposed that the presence of GLP-1-like peptides in its venomous saliva may serve various functions, though the precise evolutionary purpose remains under investigation and requires further scientific validation.

This discovery sparked intensive pharmaceutical research into developing synthetic analogs of exendin-4 that could be used therapeutically in humans. The goal was to create medications that mimicked the beneficial metabolic effects of GLP-1 while maintaining stability in the human body long enough to provide practical clinical utility. This research ultimately led to the development of the first GLP-1 receptor agonist approved for diabetes treatment.

The translation of Gila monster venom components into therapeutic agents required extensive pharmaceutical development and clinical investigation. Exendin-4, the peptide isolated from Gila monster venomous saliva, became the foundation for exenatide, the first GLP-1 receptor agonist approved by the FDA in 2005 under the brand name Byetta. This synthetic peptide (exendin-4 analog) retained the beneficial properties of the natural peptide while being manufactured for clinical use.

Exenatide demonstrated significant efficacy in improving glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Clinical trials showed reductions in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels of approximately 0.8% to 1.0% when added to existing oral diabetes medications, with effects varying based on baseline A1c levels. Additionally, patients experienced modest weight loss averaging 2 to 3 kg over 6 months, an unexpected but welcome effect that distinguished GLP-1 receptor agonists from many other diabetes medications that cause weight gain.

The success of exenatide validated the therapeutic potential of GLP-1 receptor agonists and catalyzed the development of additional medications in this class. Pharmaceutical companies created various GLP-1 analogs with different structural modifications to optimize pharmacokinetic properties, dosing convenience, and clinical efficacy. Some of these newer agents are based on modified human GLP-1 sequences rather than the lizard peptide, but they all owe their conceptual origins to the Gila monster discovery.

The weight loss effects observed with GLP-1 receptor agonists led to further investigation of these medications for obesity management in patients without diabetes. Higher doses of certain GLP-1 medications have subsequently received FDA approval specifically for chronic weight management in adults with a BMI ≥30 kg/m² or ≥27 kg/m² with at least one weight-related comorbidity. These include liraglutide (Saxenda) and semaglutide (Wegovy), representing an expansion beyond their original diabetes indication and highlighting the broader metabolic impact of GLP-1 pathway activation.

Currently, two FDA-approved GLP-1 receptor agonists are directly derived from the Gila monster venom peptide exendin-4: exenatide (Byetta) and exenatide extended-release (Bydureon, Bydureon BCise). These medications represent the direct pharmaceutical descendants of the original lizard venom discovery.

Exenatide (Byetta) was approved in 2005 and is administered as a subcutaneous injection twice daily, taken within 60 minutes before morning and evening meals. The recommended dose is 5 mcg twice daily initially, which may be increased to 10 mcg twice daily after one month based on clinical response and tolerability. Common adverse effects include nausea (occurring in approximately 44% of patients initially), vomiting, and diarrhea, which typically diminish over time. Byetta is not recommended in patients with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance <30 mL/min) or end-stage renal disease. The twice-daily dosing requirement and gastrointestinal side effects have limited its use compared to newer, longer-acting alternatives.

Exenatide extended-release (Bydureon, Bydureon BCise) received FDA approval in 2012, offering once-weekly subcutaneous administration. This formulation uses microsphere technology to provide sustained release of exenatide over seven days. The standard dose is 2 mg once weekly, administered on the same day each week regardless of meals. Bydureon/BCise is not recommended for patients with an eGFR <45 mL/min/1.73 m² or end-stage renal disease. The extended-release formulation improves adherence and reduces the peak-related gastrointestinal side effects seen with twice-daily exenatide.

Other FDA-approved GLP-1 receptor agonists, including liraglutide (Victoza, Saxenda), dulaglutide (Trulicity), and semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy, Rybelsus), are not directly derived from lizard venom. These medications are based on modified human GLP-1 sequences, though their development was inspired by the proof-of-concept established through the exendin-4 discovery. Tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Zepbound) is a dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and GLP-1 receptor agonist, representing a distinct but related medication class.

The safety profile of exenatide and other GLP-1 receptor agonists has been extensively evaluated through clinical trials and post-marketing surveillance. While these medications are generally well-tolerated, clinicians and patients should be aware of both common and serious adverse effects.

Common adverse effects include gastrointestinal symptoms, particularly nausea (30-50% of patients), vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation. These effects are typically most pronounced during treatment initiation and dose escalation, often improving over several weeks. Injection site reactions, including erythema, pruritus, and nodule formation (particularly with extended-release formulations), occur in approximately 10-20% of patients. Headache and dizziness are reported by 5-10% of users.

Serious adverse effects require clinical vigilance. Acute pancreatitis has been reported with GLP-1 receptor agonists, though causality remains debated. Patients should be counseled to seek immediate medical attention for severe, persistent abdominal pain, which may radiate to the back, with or without vomiting. Exenatide extended-release (Bydureon/BCise) carries a boxed warning regarding thyroid C-cell tumors based on rodent studies and is contraindicated in patients with a personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma or Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia syndrome type 2. This boxed warning does not apply to immediate-release exenatide (Byetta).

Hypoglycemia risk is low when GLP-1 receptor agonists are used as monotherapy due to their glucose-dependent mechanism of action. However, when combined with insulin or sulfonylureas, hypoglycemia risk increases, and dose adjustments of these concomitant medications may be necessary. Renal function should be monitored, as severe gastrointestinal adverse effects can lead to dehydration and acute kidney injury, particularly in patients with pre-existing renal impairment.

The delayed gastric emptying effect of exenatide may affect the absorption of oral medications. Medications requiring rapid gastrointestinal absorption for efficacy (e.g., oral contraceptives, antibiotics) should be taken at least 1 hour before exenatide injection. Patients should also be monitored for signs of gallbladder disease, which has been associated with GLP-1 receptor agonists.

Effectiveness of exenatide-based medications is well-established. Clinical trials demonstrate HbA1c reductions of 0.8-1.0% from baseline, with greater reductions observed in patients with higher baseline HbA1c levels. Weight loss of 2-5 kg is typical over 6-12 months. Regarding cardiovascular outcomes, the EXSCEL trial showed that exenatide extended-release was noninferior but not superior to placebo for major adverse cardiovascular events. In contrast, certain other GLP-1 receptor agonists (liraglutide, semaglutide, dulaglutide) have demonstrated cardiovascular benefits in their respective outcomes trials. The American Diabetes Association Standards of Care recommend GLP-1 receptor agonists as preferred agents for patients with type 2 diabetes who have established cardiovascular disease or indicators of high cardiovascular risk, or when weight loss is a priority.

Patients should be counseled that these medications require subcutaneous injection and proper storage (refrigeration for unopened products). Adherence to dosing schedules and gradual dose titration can minimize adverse effects. Regular follow-up to monitor glycemic control, weight, renal function, and tolerability is essential for optimizing therapeutic outcomes.

No, only exenatide (Byetta) and exenatide extended-release (Bydureon) are directly derived from Gila monster venom peptide exendin-4. Other GLP-1 receptor agonists like liraglutide, semaglutide, and dulaglutide are based on modified human GLP-1 sequences, though their development was inspired by the lizard venom discovery.

Exendin-4 shares approximately 53% structural similarity with human GLP-1 but is resistant to DPP-4 enzyme degradation, giving it a significantly longer half-life than native human GLP-1, which breaks down in approximately 2 minutes.

Common concerns include gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea in 30-50% of patients), injection site reactions, and potential for acute pancreatitis. Exenatide extended-release carries a boxed warning for thyroid C-cell tumors and is contraindicated in patients with personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma or Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia syndrome type 2.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.