LOSE WEIGHT WITH MEDICAL SUPPORT — BUILT FOR MEN

- Your personalised programme is built around medical care, not willpower.

- No generic diets. No guesswork.

- Just science-backed results and expert support.

Find out if you’re eligible

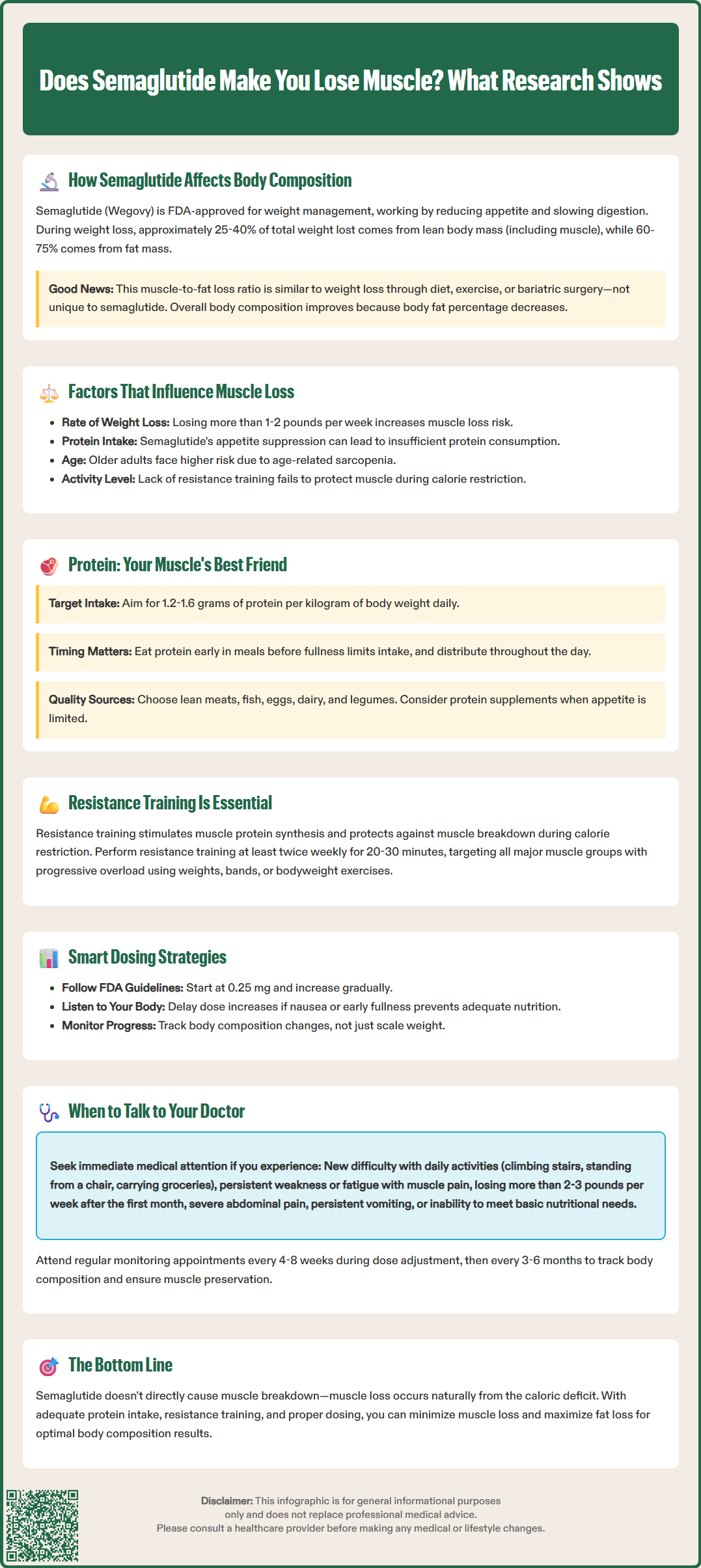

Does semaglutide make you lose muscle? This question concerns many patients considering or currently using this FDA-approved weight loss medication. Semaglutide (Wegovy) is a GLP-1 receptor agonist that produces significant weight reduction through appetite suppression and metabolic effects. Like all substantial weight loss interventions, semaglutide treatment results in loss of both fat mass and lean body mass, which includes muscle tissue. Clinical evidence shows approximately 25–40% of total weight lost may come from lean mass. However, this muscle loss appears to result from the caloric deficit rather than direct muscle breakdown by the medication itself. Understanding how to preserve muscle during treatment is essential for optimizing health outcomes.

Quick Answer: Semaglutide does cause some muscle loss, with approximately 25–40% of total weight lost coming from lean body mass, similar to other weight loss methods.

Semaglutide 2.4 mg (Wegovy) is a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist FDA-approved for chronic weight management in adults with obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m²) or overweight (BMI ≥27 kg/m²) with at least one weight-related comorbidity. The medication works by mimicking the incretin hormone GLP-1, which enhances insulin secretion, suppresses glucagon release, slows gastric emptying (though this effect may attenuate over time), and reduces appetite through central nervous system pathways. These mechanisms lead to significant caloric reduction and subsequent weight loss.

During any substantial weight loss—whether achieved through diet, exercise, medication, or bariatric surgery—the body loses both fat mass and fat-free mass, which includes muscle, bone, and water. Clinical trials of semaglutide, including the STEP (Semaglutide Treatment Effect in People with obesity) program, have shown that approximately 25–40% of total weight lost may come from lean body mass, with the remainder from fat mass. This proportion is generally comparable to what occurs with other weight loss interventions when caloric restriction is the primary driver.

Body composition analyses from the STEP trials revealed that while fat mass decreased significantly, lean mass also declined. However, the percentage of body fat typically decreased, indicating a favorable shift in body composition despite some muscle loss. Current evidence does not suggest that semaglutide directly promotes muscle catabolism through its pharmacological action; rather, muscle loss appears to occur as a natural consequence of the caloric deficit and rapid weight reduction the medication facilitates.

Several key factors determine the extent of muscle loss during semaglutide treatment, with the rate of weight loss being particularly important. Rapid weight reduction—exceeding 1–2 pounds per week—may be associated with greater proportional loss of lean body mass. Patients experiencing very rapid weight loss due to severe appetite suppression may be at higher risk for muscle wasting, especially if protein intake becomes inadequate.

Dietary protein intake plays a critical role in muscle preservation. The American College of Sports Medicine and the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics suggest 1.2–1.6 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight daily during weight loss to help maintain lean mass in most adults. This recommendation may need adjustment for older adults or those with certain medical conditions such as chronic kidney disease, where protein requirements differ. Many patients on semaglutide report reduced appetite and early satiety, which can inadvertently lead to insufficient protein consumption. When total caloric intake drops dramatically and protein is not prioritized, the body may utilize muscle tissue to meet metabolic demands.

Physical activity patterns, particularly resistance training, significantly influence muscle retention. Resistance exercise stimulates muscle protein synthesis and provides a protective stimulus against muscle breakdown during caloric restriction. A combination of resistance and aerobic exercise appears most beneficial for muscle preservation. Age is another important factor—older adults naturally experience sarcopenia (age-related muscle loss) and may be more vulnerable to further muscle decline during pharmacologically induced weight loss. Baseline muscle mass, pre-existing nutritional deficiencies, and concurrent medical conditions such as diabetes or inflammatory diseases can also affect muscle preservation during semaglutide therapy.

Preserving muscle mass during semaglutide treatment requires a multifaceted approach centered on adequate nutrition and appropriate exercise. Prioritizing protein intake is essential—patients should aim for high-quality protein sources at each meal, including lean meats, poultry, fish, eggs, dairy products, legumes, and plant-based proteins. Given the appetite-suppressing effects of semaglutide, consuming protein early in meals when hunger is present can help ensure adequate intake before satiety limits further consumption.

Resistance training is an effective intervention for maintaining muscle during weight loss. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Physical Activity Guidelines recommend resistance exercise targeting all major muscle groups at least two days per week, with progressive overload to continually challenge muscles. This can include free weights, resistance bands, weight machines, or bodyweight exercises. Even modest resistance training—such as 20–30 minutes twice weekly—may help reduce muscle loss compared to no strength training.

Patients should also consider the timing and dosing of semaglutide in relation to their ability to meet nutritional needs. Following the FDA-approved titration schedule is important, starting at 0.25 mg and increasing gradually. If gastrointestinal side effects such as nausea or early satiety are severe, the FDA label recommends delaying dose escalation or temporarily maintaining the current dose until symptoms improve. Spreading protein intake throughout the day, rather than concentrating it in one meal, optimizes muscle protein synthesis.

Nutritional assessment may be beneficial for some patients. While whole food sources are preferred, protein supplements such as whey or plant-based protein powders can help individuals meet their protein targets when appetite is limited. Additionally, individualized assessment of vitamin D, calcium, and other micronutrient status can guide appropriate supplementation to support overall musculoskeletal health. Consultation with a registered dietitian experienced in weight management can provide personalized strategies for maintaining muscle mass while achieving weight loss goals on semaglutide.

Patients should maintain open communication with their healthcare providers about body composition changes during semaglutide treatment. Significant functional decline warrants immediate medical attention—this includes new difficulty climbing stairs, rising from a chair without assistance, carrying groceries, or performing routine daily activities that were previously manageable. Such changes may indicate excessive muscle loss that requires intervention.

Schedule a medical consultation if you experience unexplained weakness or fatigue that persists beyond the initial adjustment period to the medication. While some fatigue is common during early weight loss, progressive weakness, particularly if accompanied by muscle pain or cramping, may suggest inadequate protein intake, electrolyte imbalances, or other metabolic concerns that require evaluation.

Rapid or excessive weight loss—generally defined as more than 2–3 pounds per week after the initial month—should prompt discussion with your physician. While semaglutide is effective for weight reduction, excessively rapid loss increases the risk of muscle wasting, gallstone formation, and nutritional deficiencies. Your doctor may recommend adjusting the dose, implementing structured meal planning, or temporarily pausing dose escalation.

Seek immediate medical attention for severe abdominal pain (which could indicate pancreatitis), symptoms of gallbladder disease (right upper quadrant pain, nausea, vomiting), or persistent vomiting leading to dehydration—all FDA-labeled warnings for semaglutide. Also contact your healthcare provider if you are unable to meet basic nutritional needs due to persistent nausea, vomiting, or severe appetite suppression. Healthcare providers can prescribe antiemetic medications, adjust semaglutide dosing, or refer to a dietitian for specialized nutritional support. Regular monitoring through healthcare visits—typically every 4-8 weeks during dose titration, then every 3–6 months during stable treatment—allows for assessment of body composition changes, functional status, and overall treatment response. Some clinics utilize bioelectrical impedance analysis or DEXA scans to objectively track fat mass versus lean mass changes, providing valuable data to guide treatment adjustments and ensure muscle preservation remains a priority alongside weight loss goals.

Clinical trials show that approximately 25–40% of total weight lost on semaglutide comes from lean body mass, which includes muscle, bone, and water. This proportion is comparable to muscle loss seen with other weight loss interventions driven by caloric restriction.

Yes, muscle loss can be minimized through adequate protein intake (1.2–1.6 g/kg daily), resistance training at least twice weekly, and avoiding excessively rapid weight loss. Working with a registered dietitian and following a structured exercise program helps preserve lean mass during treatment.

No, current evidence does not suggest semaglutide directly promotes muscle breakdown through its pharmacological action. Muscle loss occurs as a natural consequence of the caloric deficit and weight reduction the medication facilitates, similar to other weight loss methods.

All medical content on this blog is created using reputable, evidence-based sources and is regularly reviewed for accuracy and relevance. While we strive to keep our content current with the latest research and clinical guidelines, it is intended for general informational purposes only.

This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a licensed healthcare provider with any medical questions or concerns. Use of this information is at your own risk, and we are not liable for any outcomes resulting from its use.